“45 Years” – Interview with Andrew Haigh

by Sara Michelle Fetters - January 28th, 2016 - Interviews

Exploring Relationships

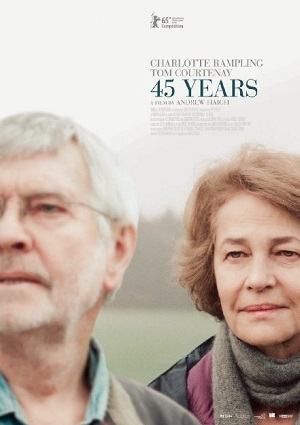

Andrew Haigh on 45 Years, Weekend and the Genius of Charlotte Rampling and Tom Courtenay

Back on January 13, this year’s Academy Award nominations were announced, and one of the most surprising nods came in the Best Actress category, cinema icon and British legend Charlotte Rampling being singled out as Best Actress nominee for her spellbinding, emotionally complex performance in 45 Years. Serendipitously, just a couple of hours later I was scheduled to have a brief phone interview with the film’s up-and-coming writer/director Andrew Haigh, and to say he was still riding high from that early morning announcement regarding Rampling would be a rather obvious understatement.

“Such a tragic morning this is,” said Haigh with a hearty laugh. “So terrible.”

“No. Seriously. It’s wonderful. I’m so very pleased. I couldn’t be happier. It feels very special. I’m still kind of shocked by it all. I woke up this morning like everyone else to watch the announcement and it was a pretty incredible moment. Even though you knew it was in the discussion, that the talk was out there for Charlotte, the reality of her getting it was something very different. I was so pleased. She’s a wonderful actress and a wonderful person. She’s done so much for the British film industry and for me personally. I’m just very happy.”

45 Years is the story of a long-married couple, Geoff and Kate Mercer (portrayed by Tom Courtenay and Charlotte Rampling), about to celebrate the anniversary hinted at in the film’s title. A few days beforehand, the pair learn incredible, tragic news involving a past girlfriend of the husband’s, the effect it has upon him leading the wife down an emotional rollercoaster of her own that takes the woman by complete surprise. It’s a simple premise made complex, intimate and profound in large parts thanks to Haigh’s delicately precise and magnetically nuanced script, Courtenay and Rampling delivering exquisitely detailed performances under his confident direction.

The movie is based on the acclaimed short story In Another Country written by David Constantine, a piece of fiction the filmmaker found himself enchanted by. “I love the short story,” he states. “It’s so beautifully written. So concise. So sparse. Yet so really, really effective. You have this body being discovered, beautiful, frozen, perfectly preserved and full of nothing but pure potential. And this discovery has a real profound effect on this relationship, and a really secure, long-term relationship, or one that is seemingly so, all of which is fascinating to me.”

“I like to explore relationships. I like to explore how we understand ourselves through these relationships. I think, this kind of news, it throws this couple off their path, and I love what it does to them, what it makes them question. The possibilities here for rich, dynamic drama just felt so immense, as far as I was concerned.”

Not that putting the various pieces together was all that simple a proposition. Constantine’s story was fairly brief and centralized, and Haigh knew he’d have to do a lot of work if he was going to transform this piece of fiction into a feature-length script. “It’s always a bit of trouble to start with,” he admits. “But I always felt like I had a pretty good handle on it. The story is told from the male perspective, pretty much, and I feel like when I made the decision to change that, to see things through the female perspective, for some reason that kind of opened it up, the story, to so many additional possibilities.”

“I added a few things. The time constraints. The anniversary party. I felt like by giving it that kind of structure and that kind of framework, while also knowing who my point of view was, I think all of that really helped. It allowed me to expand the story and build on the themes in ways I felt were genuine.”

Finding the right actors to play Geoff and Kate was always key, and Haigh understandably felt like he’d just won something akin to the lottery when Courtenay and Rampling agreed to play the roles. “It was surreal,” Haigh admits. “They turned these two-dimensional characters into something real; they brought Kate and Geoff to life. The way I like to work, we don’t really rehearse, but we go through the scene on that day, sort of walk our way through it. We’ll cut some lines that we don’t need, we might change things here and there, and overall it’s a real collaborative process. I want the actors to feel as if they are embodying the story, embodying the characters in every way, that way we can all work together to get the best out of one another that we can.”

Not that the filmmaker was counting on getting Courtenay or Rampling to play the parts. “I always like to keep it a question,” Haigh admits. “I don’t like to write with certain actors in mind, because it could both be deeply depressing when they say no and also make it difficult to cast someone else in the part if you’ve written it too obviously for a certain actor. But you can’t help but talk about people, start coming up with ideas as to who might play the parts, and quickly both Charlotte and Tom’s names both came up and I was immediately struck by how fascinating a way to go if they were to become involved.”

“It was always very important to me that we cast the female lead first, so we initially went to Charlotte before we approached Tom. She said yes, and she said it very quickly, and her agreeing to play Kate actually allowed us to convince Tom to come aboard as Geoff with far more ease than I anticipated. It was kind of like a dream process. I still can’t quite believe how it all worked out, and now I can’t imagine anyone else playing either of these two characters. They’re both just genius. They are Kate and Geoff.”

One of the more beguiling aspects of the film is the way the presence of Courtenay and Rampling ends up tying 45 Years to past classics of European cinema, motion pictures like The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and Billy Liar for him, and Georgy Girl and The Damned for her. “You can’t cast people like Tom and Charlotte and not use their past works and an audience’s familiarity with them to your advantage,” proclaims Haig. “I did feel like there was a connection. You look at The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner, clearly Tom’s character there could have grown up to become Geoff Mercer. When Geoff and Kate are discussing the past, I can picture them as they looked as their younger selves in those films, I can picture Charlotte in Georgy Girl and Tom in Billy Liar, it just feels like their characters could have known one another, could have had a relationship that would end up lasting for over four decades. That’s really quite special, as far as I’m concerned.”

“When you’re in that moment of working, you don’t always know what it is you’ve got until you get back into editing room and are like, oh, that’s really special. Even then, you can’t always know until the movie is completed if you’ve got anything. But with Charlotte and Tom, there were more than a few times where, on the day, you just had to stand back, that you knew these two knew exactly what it was that they were doing. They’re both special actors, and the way they both worked together on this was something to witness.”

I’d actually spoken to Haigh once before, back in 2011 when he came to Seattle to debut his magnificent love story Weekend, a beautiful, heartfelt film about two men who meet for a couple days of sex and debauchery and discover their mutual connection might run deeper than they had any reason to imagine it was going to. I remind him about just how honestly shocked he seemed to be with the critical and audience response to the film, about how he appeared so touched and amazed that people were enjoying it as much as they were.

“I think I always feel the same thing,” he says with a laugh. “I always feel like I’m a little bit of an outsider, so when you make these films, you tell these stories, you tend to be caught off guard when people respond to them. They’re both quite strange films, really. It’s hard to imagine people wanting to watch a movie about two guys, in Weekend, getting together to have sex and then spend so much of their time talking; I just didn’t know whether people were going to see or understand what it was I was trying to do.”

“Same with this story. It’s so amazing that people like it, that they do love it, that they’re responding to it. I don’t take anything for granted. I realize just how special it is that you can make something that touches an audience, compose a film that they can relate to, see some of themselves within. I’m really pleased that 45 Years is working for people.”

With Weekend, Haigh was looking at what could potentially be the start of a lasting relationship. In 45 Years, the director now looks at the other end of a relationship, showcasing two individuals, while not in their final years, are close enough to them to know that their time together is starting to run short. It’s both ends of the romantic relationship spectrum, a juxtaposition that, if not implicitly intentional, was one the filmmaker was still keenly aware of.

“I certainly did see them as companion pieces,” he emphatically proclaims. “45 Years is sort of sequel to Weekend, if you will, in some ways. It’s as you say. One is a story of two people looking forward at the possibilities at what might be and what that might mean for each of their lives. The other is about a couple looking back, looking at what that relationship has been, looking at how it has defined them and how it has made them who they are. Similar stories, in some ways, but ones that look at things from inverted perspectives.”

And how does the director want audiences to feel as they look at this particular story, what is he hoping they’re talking about as they exit the theatre? “I want them to feel, more than I want them to do anything else,” Haigh admits. “I want them to feel something. Anything. I want the emotions at the heart of it all to resonate with them. It’s so important, these choices that we make, the way we handle relationships, the way we deal with people, and I hope people are thinking about all of that. In a way, this film is about those things we don’t talk about, those things we repress, and how they always end up coming out in the end and force you to deal with them. If the film starts a broader conversation, as far as that is concerned, that would be pretty terrific.”

– Interview reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle