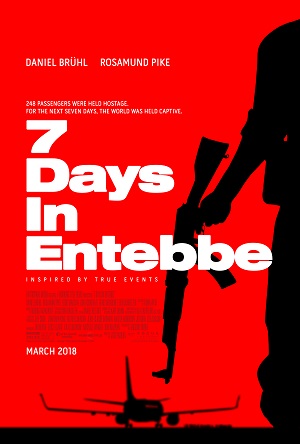

Visceral Entebbe a Frustratingly Forgettable Terrorism Procedural

It is July, 1976. An Air France flight traveling from Tel Aviv to Paris is hijacked by four armed terrorists. Two of these individuals are Palestinians. The duo in charge are a pair of left-wing German radicals, Wilfried Böse (Daniel Brühl) and Brigitte Kuhlmann (Rosamund Pike). Taking the plane to Entebbe, Uganda, they are certain the Israelis will be forced to negotiate with kidnappers for the first time in their country’s short history, all involved with the plot feeling that Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin (Lior Ashkenazi) will be unlikely to send troops onto African soil in order to rescue the hostages.

Yet, urged on by his far more militant Defense Minister Shimon Peres (Eddie Marsan), while Rabin would like to find a nonviolent solution to this problem he’s well aware a military strike might be the only way to ensure the safe return of the majority of the hostages. A small group of elite Special Forces operatives are tasked with the planning, training and potential execution of a daring raid on the Entebbe airport. With only a few days to make a decision, the Israelis meticulously explore all options available to them, while in Uganda both Böse and Kuhlmann slowly realize maybe their revolutionary principals aren’t as hard and as fast as they once thought they were.

Inspired by actual events, the docudrama 7 Days in Entebbe never quite knows what it wants to be. At times an eviscerating military procedural, at others a dialogue-driven debate arguing the merits and the shortcomings of diplomatic outreach as it pertains to acts of terror, and in subsequent moments an examination of the radical mindset as the realities of violent intervention begin to sink in, the movie is so all over the map from emotional and narrative standpoints I found it impossible to care about anything that was happening. Viscerally directed by José Padilha, unfortunately no amount of visual razzle-dazzle is enough to gloss over the plot’s more obnoxiously muddled shortcomings, any insights to be found watching the movie mostly of the didactically obvious variety.

Which is too bad, because few filmmakers have the ability to craft scenes of unsettling tension with the delicate ease and the confident precision of Padilha. Both Elite Squad and Elite Squad: The Enemy Within are kinetic thrillers that are as smart as they are invigorating, each building in electrifying power as they steamroll to their shatteringly chaotic conclusions. Heck, even the director’s 2014 remake of RoboCop, as misguided as it might have been, still featured a handful of breathless action sequences that crackled with eye-popping electricity, making it less of a unexceptional disaster than it otherwise might have been.

Padilha manages something similar here, his handling of the initial hijacking as well as his staging of the climactic Israeli assault at a remote rundown terminal located at the Entebbe airport both incredible. But it’s the stuff that happens in-between these moments, the one-dimensional characterizations and the ponderous sermonizing, that grows increasingly tiresome. It’s a heavy-handed dirge of incomplete ideas that never coalesce into anything substantive. Böse and Kuhlmann debate the merits of what it is they are a part of, realizing only too late that Germans taking Jews hostage three decades removed from the end of WWII likely won’t go over well with much of the world. Rabin and Peres banter back and forth about the merits of military action against the terrorists, the former trying to get others to understand why he’s resistant to use force while the latter plots with quietly intense Machiavellian precision in hopes of changing his mind. Then there is a third subplot involving murderous Ugandan dictator Idi Amin (a sensationally larger-than-life Nonso Anozie) that’s frustratingly undernourished, this important piece of the puzzle not really fitting into place as comfortably or as intriguingly as it by all accounts should.

All of this handicaps the actors to such a degree only a precious few of them are able to rise above the material. Along with the aforementioned Anozie, Gone Girl Oscar-nominee Pike is excellent, adding little idiosyncratic insights into her character I felt Gregory Burke’s (’71) screenplay barely even hinted at. She’s got an outstanding moment on a payphone that sent my heart right into my throat, the lump that grew there so massive I was practically sobbing by the time the scene came to an end. Israeli superstar Ashkenazi, so terrific in films as diverse as Footnote, Big Bad Wolves and Late Marriage, is also very good, and if someone ever decided to make a more in-depth biopic about Rabin here’s my vote for the actor to return in the role. Best of all is Denis Ménochet as Air France flight engineer Jacques Le Moine, the selfless humanity he brings to the story consistently invigorating.

If only Burke’s script could have been allowed more room to breathe and blossom. Between the terrorists, the politicians, the military and the Ugandans, there’s so much going on covering it all in any sort of multidimensional detail proves to be hopeless. While it’s easy to understand why the filmmakers decided against a more streamlined approach, in attempting to view this event from every single angle all at once none of them resonate in a fashion that satisfies. I just couldn’t connect emotionally to anything that was happening, and as marvelous as it all might look and sound, 7 Days in Entebbe in the end proves to be a forgettable terrorism procedural I’d rather not have seen.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 2 (out of 4)