“What They Had” – Interview with Elizabeth Chomko

by Sara Michelle Fetters - November 3rd, 2018 - Interviews

Finding the Loving Truth in Family Tragedy

Writer/Director Elizabeth Chomko on bringing her acclaimed Alzheimer’s drama What They Had to life

My great-grandmother suffered from Alzheimer’s. When I was a freshman in college at the University of Washington I would sometimes borrow a friend’s car and drive from Seattle down to Olympia to visit with her at the care facility my grandfather, my mother and her siblings decided was the best place for her. I did this oftentimes without letting anyone in my family know I was doing it, mainly because it was something I felt was personal and intimate just between the two of us. We would sit together quietly for an hour or so and she would gently hold my hand. For some reason she always remembered who I was, and as such the doctors felt it was good that I would visit every so often to help her hold on to important pieces of her past.

While these trips were fewer and further between than I maybe would have liked them to be (I was just getting used to being a collegiate scholar, after all), as difficult as these moments between us could be there’s something priceless about them that moves me towards tears every time I think back on them. I loved my great-grandmother deeply. I think she knew me better than almost anyone else, and before Alzheimer’s grabbed a hold of her psyche I can’t help but believe that there was an unspoken understanding between us where she knew more about what I was secretly dealing with in regards to my struggles with gender identity than I did, just the touch of her hand letting me know that no matter how traumatic things were she was going to continue to love me no matter what.

Writer/director Elizabeth Chomko based her extraordinary debut drama What They Had on experiences pulled from her own life. While a fictional film, elements of it were pulled straight from her own memories watching her family figure out the best course of action when her own beloved grandmother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. As such, for anyone who has lived through similar experiences her story here is a heartrending revelation. The filmmaker is unafraid to let humor and tragedy collide in order for the emotional typhoons that are an essential part of a narrative such as this ring with an electrifying authenticity they never would have possessed otherwise.

“Thank you for saying that,” says Chomko after listening to my recollections about my great-grandmother and my observations as to why I think her film works as well as it does. “Thank you for sharing your story. I appreciate that. I’m sorry about your family, too. This disease; it takes a toll. There’s like a generational grief. It’s not just about the person losing their memory. It’s also, quite frankly, it’s painful to be forgotten. With that being the case, the grief that I had watching my family struggle with her loss that was something I just wanted to kind of capture as best I could. It was a story I knew I needed to tell.”

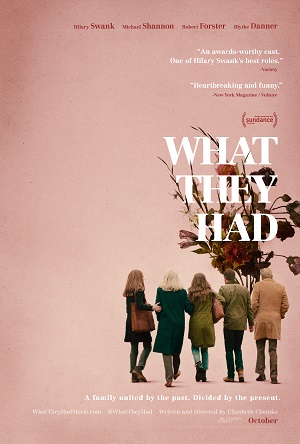

The filmmaker was making a brief pit stop in Seattle before heading out to showcase What They Had at the Orcas Island Film Festival. The plot follows California chef Bridget (Hilary Swank) as she is pulled back to her hometown of Chicago to help her brother Nick (Michael Shannon) decide what would be the best thing for their ailing mother Ruth (Blythe Danner). Her dementia due to her battle against Alzheimer’s is getting progressively worse, and Nick doesn’t believe their devout Catholic father Burt (Robert Foster) is currently the best person to be caring for their mom. As she has power of attorney over their parents, he wants Bridget to sign off on his plan to place her in a care facility, and while Burt is adamantly against this plan in the end whether he likes it or not ultimately this is his daughter’s decision to make and no one else’s.

Featuring incredible performances from all four leads (as well as a fifth, magnetically subtle supporting turn from Taissa Farmiga as Bridget’s college-aged daughter Emma), Chomko’s drama has a stunning ability to mine difficult emotional terrain with an observational restraint that suits the material nicely. While the film wears its heart on its sleeve, it’s is equally willing to let the audience laugh at any number of surprising moments, things briskly moving through a myriad of emotions ranging from anger, compassion, understanding and regret with a beguiling specificity I found stunning.

“I didn’t set out to be a filmmaker,” comments Chomko unprovoked. “It just ended up being a very organic process for me. I was a playwright and an actor, and I just felt like, frankly, at my grandfather’s funeral, I felt like I didn’t know what to do with this feeling of loss and grief and not wanting to accept that this was the end of this family lore. I didn’t want to think this was the end of my grandparent’s love story. I couldn’t accept that this grief was just what we had to go through. You get to that place of grief where you just want to climb out of it, that physiological response of there’s got to be a workaround to get over it. You feel like there’s got to be a shortcut. I’m the eldest grandchild. There had to be a way for me to tell their story and help everyone heal.

“I wrote the screenplay very quickly and I didn’t expect any of this to happen with it. It [the screenplay] just kind of kept guiding me to continue to work on it and work through whatever it was that I was trying to work through. From whatever organic place that all came from, I think it allowed other people to want to be a part of this journey. I just am incredibly fortunate that those other people were the kind of collaborators that I ended up with. Those were good moments. This was a good thing.”

One of those good things happened to be Chomko’s script winning the prestigious Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Nicholl Fellowships in Screenwriting. “That was a wonderful day,” says the filmmaker happily, “I did not expect to win by any stretch. I got the call from Robin Swicord, who’s the head of the committee, and then I heard the rest of the committee on speakerphone. I don’t remember what was said, but I got off the call and I remember bursting into tears. We had this luncheon where they all spoke about the script and what it meant to them, speaking to all of us who had won. Just hearing these committee members validate this story and my voice as a storyteller was everything. It was life-changing.”

“The Nicholl really got the film a bit more exposure,” continues Chomko after a quiet moment or two of reflection. “It certainly helped with my confidence, but it also got the film just more momentum and exposure. It got people to start to notice [the script] and to read it. Our producer, Albert Berger, he was on the Nicholl committee, so he and his partner Ron Yerxa, they decided they would come on as producers.

“They’re legends. They’re so beloved by the independent film community. It just really gave the project a validity and a sense that these A-list actors we were talking to like Hilary and Michael would really be able to trust that they were coming aboard something good. It was their presence as producers that actually allowed us to show the script to Hilary. Thankfully she read it and loved it. Hilary really helped me see that character, Bridget, which was sort of an enigma to me because it was like the one that was the most me. Her insights helped push the details forward. She became this woman that I was trying to conjure. More, Hilary really was a partner and a champion. She just helped at every stage. Hilary helped keep the project to keep moving forward.”

Her affinity and connection to the material is instantly obvious. A two-time Academy Award winner for Boys Don’t Cry and Million Dollar Baby, Swank’s performance as Bridget ranks right up there with the best the actress has ever given. What makes her work even more impressive is that her character spends almost as much time observing what the others are doing and saying as it pertains to Ruth as she does trying to figure out for herself what’s the best thing to do for her mother. There is a level of heartfelt indecision to her performance that’s uncomfortable to witness, Swank allowing Bridget to live in the moment in ways that are truthful, heartfelt and unbearably poignant.

“That’s the challenging thing, isn’t it?” asks Chomko candidly. “The conventional wisdom about screenwriting is that you want to have a hero who’s got agency, who’s got an objective, and they will pursue that objective no matter what obstacles get in their way. But what happens if that objective is that you don’t quite have your agency developed? How do you deal with that type of indecision in the midst of a crisis? I think that’s a female experience. I think that’s what it means to sometimes be female in a nutshell. It’s often a female challenge. All these men telling you what you need to be doing, what the right thing is, never giving you the freedom to make your own decisions and live your own life. That’s just some of what Bridget has been dealing with and yet now, in this instance, she’s the one with all the power. How do you deal with that?

“I’m not sure what the right thing is. I don’t want to just bully through it all, to bulldoze through these questions. I want to try to figure it out. A woman discovering her agency for the first time or for the first time in her own family, I think that’s a story deserving of being told. It’s such a female trajectory. It’s a female coming of age.

“That’s something Hilary and I really connected on in a very instinctual way. She lived in that beautifully. I think it makes Bridget a real woman, a woman that I know and I am. Hilary really showed that. It was a joy to be able to show that in a character with her. It was such a joy, I think, for us to be able to do this together.”

As essential as it was to showcase this side of the story in such exacting, if slightly prickly, detail, it was equally important to Chomko to bring humor and levity into the film. This is mainly accomplished through Shannon’s Nick, the overworked, over-stressed bar owner the one who has constantly been trying to help their father care for Ruth as he’s the only one still living in Chicago. The director grants the actor the freedom to make the character his own. But as funny as he can be there is an exhausted pent-up rage bubbling beneath the surface that Shannon unleashes with a sudden ferocity that’s can be startling, comedy and tragedy intermingling with a deft precision I personally found incredible.

“He’s such a great actor,” flatly states the director. “He just is. You know the moment you meet him he’s going to do something incredible and you just hope you’re lucky enough to catch it with the camera.

“The role, Nick, he started off as being inspired by my uncle. But then as I was writing the script, Hilary’s character is very much me and the things that I struggle with about myself. I’m a pleaser, and I’m a caretaker, and I’m always worried about what everybody else needs. I have that voice in my head that is like, what are you doing? Just be honest. Who cares what they think? Stop being a liar. You’re being such a chicken-shit about it.

“It was that voice that helped Michael’s character develop as it did, and he just seemed to tap into that without my even having to say anything. It’s like he heard those two voices in my head, understood what it is they’re constantly trying to figure out and instantly knew what facet of that he was supposed to be playing. Michael and Hilary together, they just stepped into that. They just got it. I have no idea how. It’s a testament to how amazing both of them are.

“With Michael specifically, I just think he got this guy. He knew who Nick was. We didn’t really talk that deeply about it. We didn’t have a lot of time to prepare. The approach that I had was like there was so much that I had to deal with and consider, so much I had to do and make decisions about and oversee, that I really just wanted all of the actors to take these characters who were perfect for them and then make them their own. I thought everyone was perfectly cast. I wanted them to run with it. And if a line didn’t work, I wanted them to say something else. I wanted to do things a few different ways. I knew if there were any problems that we would find a way to figure them out.

“Michael tapped right into that. He just got the guy. For whatever reason, t just felt like such an easy thing for him. It looked so effortless. He’s a guy who can do anything. Michael is one of the greatest actors of our generation. I mean it. He can do anything.”

It’s apparent speaking with Chomko just how impressed she was with the collective efforts of her cast, continually singing their praises at every opportunity. No more so than when she gets to Danner, who arguably had the most difficult task in the entire film portraying Ruth with a care, sensitivity and a restraint that allowed the character’s mental struggles to resonate on a personal level and not feel melodramatic or facile. “She’s wonderful,” says the director when asked about the actress. “I can’t sing her praises enough. Blythe was so brave to come into this with very little time to do any kind of preparatory work, and she knew nothing about Alzheimer’s. She had never encountered or spent any time with memory loss in her family. She really took an incredible leap of faith to play this character. She threw herself into my hands and just sort of let go in the most beautiful way. I was constantly amazed.

“She did do research. She looked at a lot of the family video that I have of my grandmother. That was who I wanted to really celebrate in the film and Blythe responded and understood that. My grandmother just became this sort of childlike presence and childlike spirit. She was this ghost kind of hovering in the margins. Blythe is really lyrical with her depiction of this, and I think it’s so beautiful. It feels very true to the way that I remembered my grandmother being.”

As for Forster, in many ways Burt is the driving force behind all the underlying angst, turmoil and trauma Bridget and Nick are being forced to deal with. But, as belligerent and as unyielding as he appears, everything this man does still comes from a place of unadulterated, unvarnished love. Love for his granddaughter. Love for his son. Love for his daughter. And, most of all, an undying love for his wife.

“Robert is just a special actor,” remarks Chomko. “That character is so vital to the story. I think he’s a product of growing up the way he grew up on the farm. Men of that generation who served in the military, it’s a Midwestern sort of boundary-lessness to kind of tell your generation how to live, right? Let me tell you what your problem is. I’ll tell you what your problem is. There’s your problem. You gotta just do this. It’s that easy. It’s that simple. These were the standbys men like this were raised on. It’s all they know.

“Of course, life is complicated and has only, I think, gotten more complicated for subsequent generations. Certainly as it concerns gender dynamics, and that was something that was very important to me as a woman to spotlight. It was just instinctual to me to emphasize that.

“I mean, I didn’t set out with a political agenda, but this is the kind of stuff I think about. I think that those gender dynamics, as you get older, I think there’s a kind of thing where you think to yourself, ‘You young kids. You think you know everything.’ And, of course, we do, we do think we know everything. But that doesn’t mean the older generation actually has all the right answers, either. This was something I felt like I needed to explore.

“There’s this domineering streak. It’s just that kind of conventional Midwestern morality. Church, parish, family; that’s what you’re loyal to. You don’t ask questions. You don’t get weird about it. You just sort of put your head down and do their version of the right thing. But here’s this situation where there is no right thing, right? How does that unravel when suddenly we have to look at everybody else’s morality? Or of these other generations and the diasporas of moving to a place in California with totally new, totally different moral codes? How does that then unravel this kind of old school, Midwestern morality? Robert had to portray all of that and more. I just think he’s a tremendous actor.”

As for the movie itself, while Chomko is understandably happy about the critical response to her debut, it is the reactions from audiences that she takes the most pleasure in. “I wish I would have had a movie like this 16 years ago when my grandmother was diagnosed,” she states plaintively. “I was 21 and absolutely devastated because she was 68 and way too young. I think if there had been a movie like this, I just might have had a little more hope because I think Alzheimer’s is brutally painful, and it only gets more painful as things progress. As things got worse with her, she just died a few months ago actually, but as things got worse with her, I kind of look back on those earlier days where she was still in that place where we were still having fun and where I was able to hang out with her as though we were schoolgirls together and imagining this could’ve been what she was like at 12. It was like being able to time travel with her. That was a precious thing. It was something to be enjoyed.

“For audiences, though, I think the questions about morality and mortality, those are all there to ponder if they want to. If their families are dysfunctional, well then I hope that by watching this they get the chance to feel that they’re not alone. I think that’s what I hope that people take away from the film. But whatever they feel, whatever they feel, I just hope that feeling is what they take home with them. That, really, is the only thing I could ever really, truly hope for.”

– Interview reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle