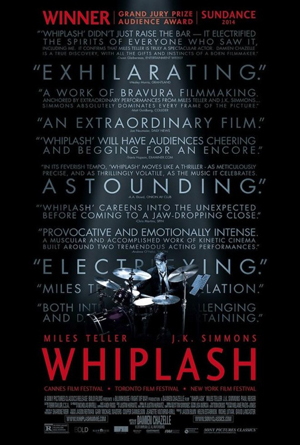

Electrifying Whiplash a Rim Shot to the Soul

Andrew Neiman (Miles Teller) dreams of greatness. A 19-year-old freshman at a prestigious New York music academy he’s already caught the interest of Terrence Fletcher (J.K. Simmons), the school’s world-renowned jazz conductor known equally for discovering talent as he is for his vicious methods of bringing it out of his players. One thing leads to another, Andrew not only finding himself part of Fletcher’s award-winning ensemble but suddenly its most abused member. It’s psychological warfare of the first degree, teacher using every one of his belittling, emotionally manipulative tricks in order to see his prized pupil either rise to the occasion and grab the mantle of genius or wallow in ridicule and failure as his ego is crushed by tone-deaf mediocrity.

Whiplash, based in no small part on the filmmaker’s own time spent trying to please the dictatorial leader of his own High School jazz band, is writer/director Damien Chazelle’s follow-up to his award-winning debut Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench. Where that movie was quiet, this one has no problem cranking the volume up to 11. Where that drama tread along its narrative path with such subtlety you’d be forgiven for missing some of its more intimate emotional nuances, this one wears its intentions on its sleeve telegraphing all aspects of what its story is and where things are headed right in its very first scene. The films are night and day from one another, and save for the fact each revolves around musicians there’s little connective tissue running between them.

That’s fine with me, Whiplash a daring, go-for-broke spectacular that focuses on its two main characters with laser-like precision never losing sight of the bigger picture or the themes it’s longing to explore. The movie is a cacophony of emotional arrogance run amok, looking at the teacher-student relationship in ways that, while not new, still add plenty of fodder to the conversation. Can greatness be achieved without suffering? How far can a teacher go to bring it out of their students? Does one have to experience pain, negativity and disappointment in order to find the inner strength to rise above and do what no one else has before? Are the worst two words in the English language “good job,” saying them nothing more than verbal permission for averageness to flourish and blossom?

These are just a few of the questions Chazelle is interested in looking at, and anyone who has ever watched An Officer and a Gentleman, Hoosiers, Stand and Deliver, Any Given Sunday, The Miracle Worker, Miracle, Akeelah and the Bee, The Breakfast Club, The Karate Kid and so many other motion pictures of a similar ilk knows where all this is headed early on. But as hard as the instructors in all of those films could be, for as much as they could push their charges to their respective breaking points and then well beyond, none of them, save maybe Louis Gossett Jr’s Sgt. Emil Foley in An Officer and a Gentleman, can remotely compare to Simmon’s Prof. Fletcher. The man is more Bob Knight than Knute Rockne, more Gordon Gekko than John Keating, so unrelentingly awful in both behavior and action there are not words to describe his grotesque conduct in exacting enough detail.

At the same time, he does understand his students, assesses their skills and their attributes with shocking clarity. More, some of them, erstwhile drummers like Andrew, seem to thrive on the abuse, looking at his vitriol, anger and browbeating as a constant challenge to improve their skills to the point no one anywhere can match them beat for beat and note for note. He gets under his pupils’ skins so fully they almost can’t help but go so far as to bleed in order to surpass expectation, using every last ounce of want, desire, longing and, yes, talent in order to find success.

Teller, a young actor who instantly shot onto the radar with his stunning debut in Rabbit Hole only to follow that up with turns in second-tier efforts like Footloose, That Awkward Moment and Divergent that were better than the films deserved, delivers a performance that defies belief. For those who thought he transformed himself into a star with his superlative work in The Spectacular Now, his Andrew is another step towards superstardom. He pours himself into the young drummer with pitiless savagery, crafting a central character whose drive and tenacity are relatable yet whose actions are so self-centered and abhorrent he’s moderately detestable. There is a fearlessness to this portrait that’s stupendous, and whether one likes the kid or hates him and all he allows himself to be transformed into taking your eyes off Teller for a single solitary second is an utter impossibility.

He’s matched by Simmons, and if Andrew isn’t the most pleasant kid to spend time with than his instructor is downright abominable. There’s little about this guy that’s redeeming, and whether his heart is in the right place or not his actions are so sickening finding justification for them isn’t easy. All the same, the veteran character actor known for films as eclectic as Juno, Spider-Man, The Gift and The Mexican (as well as those omnipresent – and annoying – State Farm commercials) is on fire, rattling off obscenities, put-downs and other verbal lacerations as if he was the Picasso of profanity. He makes the teacher shockingly three-dimensional, finding layers hidden within the persona that, while not making his actions forgivable, in some way does make them understandable, and as such Simmons allows intimate access to Fletcher’s interior workings in ways that are hardly comfy.

Chazelle refuses to supply easy answers to any of the film’s more loaded questions, offering up a rousing, and in many ways uplifting, finale that in no small way makes one wonder if he is in fact forgiving Fletcher for his misdeeds and proclaiming Andrew’s selfishness as a necessary evil for genius to blossom. Anyone who has had a wannabe Drill Sergeant for either a coach or a teacher knows where the jazz conductor is coming from, and while some individuals thrive under such tutelage others can be permanently scarred by the experience.

As such it is during the climax when things get the murkiest, teacher and student engaged in a battle of wills that, ever so slowly, morphs into something altogether different, each in suddenly such astonishing symmetry with the other the musical magic they are on the verge of creating is something remarkable. Is Whiplash a celebration of Fletcher’s tactics? Or, instead, is Andrew rebelling in such a way the confrontational professor’s only recourse is to assist and aid him in this rat-a-tat-tat insurrection? Whatever the answer, if there even is one, what’s never in doubt is that Chazelle’s latest is a musical mindblower, the power and the fury of this dramatic paradiddle a vibrant rim shot to the soul that’s nothing short of breathtaking.

Film Rating: 3.5 out of 4