Aloha True to Its Characters, Indifferent to Its Plot

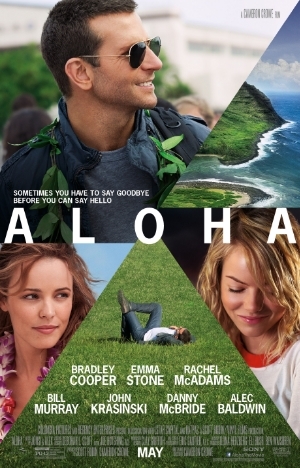

Military contractor Brian Gilcrist (Bradley Cooper) is lucky to be alive, let alone thankful to still be employed by his billionaire boss Carson Welch (Bill Murray). He was literally blown up while working a deal in Afghanistan, trafficking in the grey areas for self-serving reasons the powers that be weren’t as clueless about as he thought. But, now that he’s recovered, they’re giving him a second chance, sending him to complete a straight-forward deal with local Hawaiian elders revolving around the U.S. Space Program in Honolulu, the place where his career in the armed forces began and the site of his greatest personal and professional triumphs.

But, not only is Brian saddled with a fast-talking, fiercely determined military liaison in Capt. Allison Ng (Emma Stone), he’s also back face-to-face with the former love of his life, Tracy Woodside (Rachel McAdams), a woman he walked out on almost 13 years prior for a variety of reasons, most of them selfish. She’s now married to another Air Force pilot, John (John Krasinski), but it’s clear to everyone, including the pair’s children Grace (Danielle Rose Russell) and Mitchell (Jaeden Lieberher), that there’s still something simmering between the two, an unspoken bond filled with regret and remorse that has both wondering what might have been.

There is an actual plot as far as writer/director Cameron Crowe’s melancholic romance Aloha is concerned, something to do with Carson Welch’s intentions to take control of the corporate push into outer space and the sanctity of a sky devoid of weapons, but in all honesty caring about any of that is difficult. It’s hard not to get the feeling that the man behind modern classics like Almost Famous, Say Anything and Jerry Maguire doesn’t care about any of it, indifferent to the central motifs he himself scripted for his main characters to navigate. None of it matters particularly much, a climactic sequence involving a hacked satellite, a rocket launch, and ancient treaties the wealthy figure they can circumvent for no other reason than they can, treated with as much import as a cartoon chicken attempting to cross a dusty road with a broken wing while hopping on one leg.

As bad news goes, that’s pretty heinous, and there’s little I can come up with to give Crowe a pass for any of his apathy to his film’s main diminuendos. At the same time, it’s hard not to walk out of Aloha with a smile, the other stuff lurking inside the narrative, the way the characters interact, how they communicate, the subtle, delicate little human truths they discover along the way, much of that isn’t just terrific, it’s shockingly close to sublime. While believability is an issue, make no mistake on that front, connecting with the principals and what it is they are all dealing with to varying degrees somehow never is. More than that, the filmmaker stages a dilly of a final sequence, the last images haunting in their emotional clarity and power to amaze.

Crowe has always had a knack for staging long sequences of dialogue between individuals and groups that, in lesser hands, would border on being intolerable but in his hands is natural, authentic and achingly pure. That talent is on display in spades with Aloha, Cooper having a number of sensational scenes with both Stone and McAdams that are wonderful. Many of them have that whip-smart give and take reminiscent of the filmmaker’s idol Billy Wilder, each crackling with an old Hollywood electricity that’s utterly sublime. They enliven the material, give it a reason to exist, and even if the twists and turns they’re attempting to sell dip into melodramatic sentimentality they still manage to keep things so emotionally pure the overall effect is undeniably persuasive.

If anything, it’s what is unsaid that ultimately gives the final feature its heft and oomph. Heck, one entire subplot involving Krasinski (who has never been better) revolves entirely around his character’s inability to talk about himself and what it is he’s going through, leading to a glorious bit between he and Cooper that’s acted entirely with body and facial movements. Crowe subtitles the moment, but as great and as humorous as his words are they’re also unnecessary, both actors delivering everything we need to know with stupendous, almost tender grace.

But none of that left me prepared for the last scene. There’s a twist lurking inside the movie, one that isn’t that much of a surprise as all the clues are there from the first second the two female characters most associated with it meet up with Brian after he lands in Honolulu. None of them talk about it, none of them give verbal hints as to what is going on and why, yet all of it is there, readily apparent, making the last dance and embrace between two people a dazzlingly magnetic grace note that ripped my heart clean in two and sent me out of the theater with a smile.

All of which makes Aloha even more of an enigma and a head-scratcher. It’s easy to see what Crowe wanted to talk about, it’s obvious the moments that are nearest and dearest to his heart (an early foray to see real life Hawaiian activist, personality and overall legend Dennis “Bumpy” Kanahele is sensational). But that central story? The stuff dealing with aeronautics, NASA, space travel and weaponized satellites? It’s a waste of time, and why the filmmaker went with that as his primary focus I’ll never understand. Yet, thanks to the affecting purity of the relationships and the beauty of those last images the film is far from a failure, and I can’t help but think I’ll be pondering and mulling over moments and beats central to it for an awfully long time to come.

Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 2 ½ (out of 4)