“Suffragette” – Interview with director Sarah Gavron

by Sara Michelle Fetters - November 5th, 2015 - Interviews

Victory and Sacrifice

Director Sarah Gavron Gives Voice to Unsung History with Suffragette

Director Sarah Gavron didn’t rest on her laurels after her first theatrically released feature Brick Lane met with almost universal acclaim back in 2007. While pondering a number of follow-up narrative projects, she found herself obsessing over the documentary Village at the End of the World. Released in 2012, it chronicled the inhabitants of a small Northern Greenland township with a population of 59 human souls, the small, deeply personal endeavor putting an intimate spotlight on those eking out a living in one of the harshest environments on Earth.

But, even then, she was beginning to be drawn to another story, one revolving around the women who struggled and fought for the right to vote in England at the turn of the 20th century. With all that was going on in the world, with the skirmishes being fought in the Middle East and in Afghanistan, with women the world over beginning to demand equal pay for equal work, looking back at this era in history just felt right. On top of that, much to the filmmaker’s shock, the suffragette movement in Great Britain was a story that, for all intents in purposes, had somehow never been told inside a major feature film. This was a slight she felt up to the challenge of ending.

“I couldn’t believe nobody had done it,” says Gavron with frank honesty “I couldn’t believe it hadn’t been told before now. I was quite shocked by that.”

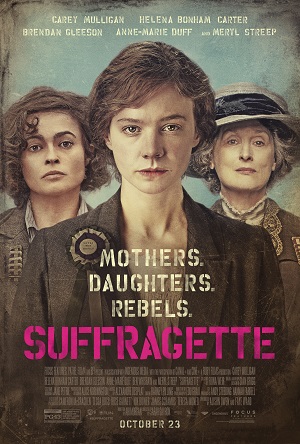

The filmmaker was in Seattle to show off her new film Suffragette starring Carey Mulligan, Brendan Gleeson, Anne-Marie Duff, Romola Garai, Ben Whishaw, Helena Bonham Carter and, in a small, if vitally important cameo, Meryl Streep. Sitting down for a few minutes at a local downtown hotel, we briefly chatted about all the disparate influences that led her to make the movie, the filmmaker teaming with Shame and The Iron Lady screenwriter Abi Morgan to help her bring it to life.

“Going into the research with Abi, we found all these stories about women that were just so contemporary and resonant,” recalls Gavron. “Stories about women being abused in the workplace, about sexual violence, about the gender pay gap, about police surveillance, these are all stories we’re hearing about right now, not just a century ago. They all seem to resonate with what is taking place across the world. The parallels were just so obvious.”

“We wanted the story to be about an ordinary woman, not someone like Emmeline Pankhurst, who does appear in the story. We wanted it to be about a working woman who would sacrifice so much for the fight but without whom victory would not have been possible. This was always the starting point for both Abi and I as we started putting all the pieces together.”

Thus was born Maud Watts, a laundry worker who had been giving herself body and soul to her employer since before she was a teenager. Portrayed brilliantly by Mulligan in the film, the character is a composite of a number of real stories Gavron and Morgan came across while doing research. It was through these actual accounts of women who had lost, suffered and persevered that led them to ultimately construct the character as they eventually did.

“We found three women whom essentially all helped Maud come to life,” the filmmaker recollects. “We drew on them. We thought, how do we make these accounts accessible to an audience? What is it about their stories that draw us in? We found Maud in this research. If you read those unpublished diaries, memoirs and letters you find women who worked at a laundry in East London who got involved in this activism, women who sacrificed their families, their very lives, in order to get the right to vote. It’s heartbreaking, yet also inspiring, and those were key emotions Abi and I wanted to tap into.”

As to the prescient nature of the narrative, while Gavron would like to take credit for crafting a motion picture that taps right into the middle of so many conversations in regards to women’s rights around the globe, she fully understands just how big a part coincidence played as far as that was concerned. “The movie found its moment,” she admits. “While we were indeed inspired by much of what was going on, the simple fact is, had this movie been made 15 years ago, 10 years ago, maybe even five years ago, it’s doubtful people would be paying as close of attention as they are right now. I’m sadly not sure the world would have been ready to hear it so, in that way, we were lucky and it was a little bit of happenstance.”

“But we were conscious of what was going on. Make no mistake. When the police archives in Britain opened in 2003, they revealed this massive surveillance operation against the women in the suffrage movement. It just blew our minds. All of these police, going undercover, taking pictures of these women with cameras concealed on tripods. How they were ordered to attack these women so brutally. It revealed so much, and all of it seemed so relevant.“

“We never wanted to make a piece of history that you would feel distanced from. We wanted to make a film that reminded you how hard-fought this battle was. Wanted to remind people just how far we’ve all come. But we also wanted to remind people what was still at stake, what could be lost, while also reminding [viewers] about how there are so many women in the world who are still fighting for basic human rights. There are 62-million women in the world who do not get an education. One in three women experience sexual violence in their lifetime. It’s all very relevant, and it’s all part of our story set over a hundred years ago.”

One of the keys to the film is the fact that Maud refuses to proclaim herself a suffragette for much of the motion picture. She’s a mother. She’s a wife. She’s a worker in a laundry. She is all of those things and more, but she does not consider herself a revolutionary. She is just doing what she feels is right, and in the process becoming they type of unsung hero movements of all types need playing a vital role if success is to eventually be found.

“I think that is so true,” says Gavron. “If you look at it, look at history, it’s often working people, working women, working men, who have been the backbone of change. So much of these sorts of movements are born out of inequality. Working people begin to question the situations they are in, they begin to evolve, and that’s usually were the spark as it pertains to change is initially struck. They’re fighting for their rights.”

As far as cinematic parallels go, the closest companion Suffragette can claim is arguably the 1979 Oscar-winning classic Norma Rae with Sally Field. But, in that movie, the lead character’s rebellious fire is lit by a man, her clamoring to get her factory Unionized driven by her relationship with men. Here, this story, it’s all propelled by women, every second of it, Maud’s passions for the movement initially stoked by her growing friendships with characters portrayed by Duff and Carter.

“We’re so used to in cinematic narrative that, if you have a female character, she’s often the girlfriend, she’s the wife, she’s the prostitute, she’s the sidekick, and even if she’s the protagonist you’ll still have a man leading her where she will need to go,” proclaims Gavron. “It’s all so tiresome. We didn’t want to go down that road. Not only did we want to put women at the front of this fictional story, they were at the front of this story historically, the historical record shows us this time and time and time again.”

“We do have some great men in the film, and of course they all have different shades, but this story was always about these women who spurred one another on and found the support they needed in amongst themselves. They crossed class, crossed ages, all in order to come together as one during this battle.”

It is curious that, for most at least, the most effective and long-lasting movie focusing on the suffragette movement in England is Disney’s Mary Poppins, a fact not lost on the filmmaker. “I love that movie, too,” she admits with a laugh. “That song [“Sister Suffragette,” sung by Glynis Johns] really is infectious. But it is the sanitized version, isn’t it? She’s a little bit patronized during that moment. Through today’s lens it’s probably a little offensive, but the movie is just so good I don’t think anyone would care to notice.”

“But, in all seriousness, it’s extraordinary to say but the [suffragette movement] was not on the curriculum when I was in school. It wasn’t taught, and it’s only very recently that it has worked its way into the lesson plans in the U.K. But it’s still only barely touched on, and students do not get the full story. We had a number of female advisors on the movie. All of them made sure to remind us constantly how big a battle it was to have these stories recognized by universities as being important. It was important to us to keep things like this in mind as we were making the movie.”

Then there is the conversation running rampant throughout Hollywood, the one a film like this can’t help but be a part of whether the filmmakers wanted it to be or not. With the outcry over directorial opportunities for women far from equal in comparisons to what is offered to their male counterparts, Gavron understands just how big an anomaly Suffragette is.

“I do think these conversations have been constructive,” claims the director. “You’ve got actresses like Patricia Arquette talking about sexism in Hollywood. You’ve got powerful people like Meryl Streep calling attention to the inequity as it pertains to film crews. Our culture in so many ways is reflected by the cinema. We need to have diversity behind the camera. Our children need to be seeing these stories. It’s kind of crazy, isn’t it? But the fact that all of this is part of the conversation now, it’s so positive.”

“For me, it’s all about role models. In my early 20s, when I saw women like Jane Campion making films, Mira Nair, Kathryn Bigelow, Claire Denis were all making films, I thought to myself it was all possible, I could be a director. Anything seemed possible.”

As far as this film goes, it’s impossible to imagine it working near as well as it does had Mulligan not been cast as Maud. It’s a sentiment the filmmaker wholeheartedly agrees with. “We always wanted the caliber of cast that we ended up with,” states Gavron. “There are a lot of times you get pushed into certain directions for financing and marketing reasons, not because you want to fill the roles with the best possible actor. That was thankfully never the case here. We wanted to bring together this wonderful, eclectic group of British talent – and Meryl, of course – and see them all on-stage together. To see it happen was just marvelous.”

“With Carey, there is no doubt having her around was a great thing. She can say so much without saying a word. That’s such a rare quality. You see these tiny little shifts and you know what she’s feeling. And she’s playing a character who is so internal, especially at the beginning, and it was so critical that we had someone like her who could convey so much just by the camera being held on her. That’s why we went for the close-up. Carey holds that camera so brilliantly. She’s amazing.”

Ultimately, though, Suffragette will rise or fall based entirely on how general audiences react to the central human journey at the heart of these historical events. Gavron isn’t worried. “When you watch the film, you realize how big the moment was, how this movement represented more than just getting the right to vote,” muses the director. “I hope that young people feel that sense of agency. That they are inspired and realize that they need to be counted, that they need to use that vote to make positive change in the world. The film meant a lot to us as we were making it. I now hope it means a lot to the viewers who take the time to watch it.”

– Portions of this interview reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle