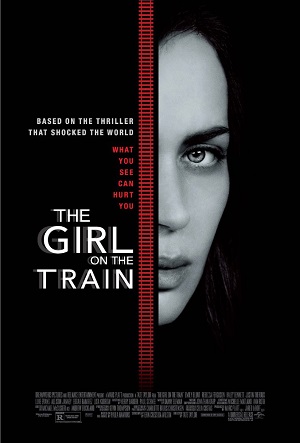

Blandly Tiresome Girl an Almost Total Misfire

Rachel Watson (Emily Blunt) is a drunk. Unable to get over the divorce from her former husband Tom (Justin Theroux), she rides the train into the city each and every day seemingly just because it goes right past her former house. From there, she can see him, if only for a moment or two, lovingly embracing his current wife Anna (Rebecca Ferguson) and the pair’s infant daughter, dreaming of the life that might have been had things between them gone just a tiny bit differently.

She also makes up stories about the beautiful blonde and her seemingly virile husband who live just a few houses down, imagining an entire, blissfully happy fantasy life for the two even though she’s never made either of their acquaintances. But when she spies the woman kissing another man from the train’s window, Rachel is furious, so much so she ends up going on an alcoholic bender the likes of which she hasn’t experienced in months. Waking up at home bruised, battered and covered in blood, she has no idea what happened the night before. Worse, the woman she’d been observing from the train, Megan Hipwell (Haley Bennett), has gone missing, her husband Scott (Luke Evans) the primary suspect in her disappearance.

This is the basic plot of director Tate Taylor’s (The Help, Get On Up) adaptation of Paula Hawkins’ best-selling novel The Girl on the Train. Early on, screenwriter Erin Cressida Wilson (Secretary, Chloe) attempts to emulate the author’s triptych storytelling style, presenting the narrative from all three woman’s varying perspectives, planting the seeds of the darkly disturbing, sexually depraved mystery to come. She and Taylor do a wonderful job setting the mood, editors Andrew Buckland and Michael McCusker (The Wolverine) moving between Rachel, Anna and Megan’s varying points of view with apparent ease.

All of which is great for about 20 minutes, the first act of the film an intriguing netherworld of a possibility and intrigue that’s enthralling. But in stunning short order, Taylor’s handling of things starts to become less self-assured, while at the same time Wilson’s script has trouble maintaining its focus, and suddenly what worked reasonably well enough on the page becomes downright laughable when depicted up on the screen. Worse than that, though, there’s just no energy propelling events forward, Rachel’s supposedly dogged pursuit of the truth having all the enthusiastic drive of a kiddie car stuck going in reverse. The movie is flat-out boring, and if not for Blunt’s sublime, fully committed performance, as well as the whacked-out barnburner of a lunatic climax, there’d be shockingly little worthwhile to be talking about.

The mystery itself, the solution to which I admittedly had pegged about halfway through reading the book, is honestly fairly lame, and had this been an episode of “Prime Suspect” Det. Supt. Jane Tennison would have had things solved by afternoon tea. All of which makes the detectives here look even dumber than they do in the book, which basically means Allison Janney is stuck portraying a moron, and the fact she never follows any of the more obvious clues is a major sticking point I found impossible to get past.

More than that, the two side stories involving Anna and Megan just aren’t interesting. If anything, both women come off looking like shrill, soulless ciphers, both sucking all of the oxygen out of the picture as they manipulate their way from one crisis to the next. Ferguson and Bennett, both fine actresses who deserve better, are stranded with nothing substantive to do or play, the interior layers that potentially could have made their characters at least moderately interesting never materializing at any point during the proceedings.

The ace in the hole, of course, is Blunt. She’s all-in, diving into Rachel with fearless abandon, and while her depiction of alcoholic decrepitude isn’t on the same level as say Ray Milland’s in The Lost Weekend or Mickey Rourke and Faye Dunaway’s in Barfly, that has more to do with the patronizing silliness of the story itself than it does with her ferocious devotion to the role. Blunt does a terrific job of cementing Rachel as an unreliable narrator, and thus her depressed frenzy as she tries to connect one dot to the next without being able to recall how they are supposed to fit together is instantly, tragically relatable, and it’s all thanks to her.

But it’s all for naught, and even with the unhinged lunacy of the climax proving to be a cringe-worthy force of unintentional, and uncomfortable, hysterics, The Girl on the Train proves to be so leadenly paced and so blandly shot – this is sadly far from the usually reliable cinematographer Charlotte Bruus Christensen’s (Far from the Madding Crowd, The Hunt) finest hour – even its great moments sink underneath the surface like a lead balloon. As thriller’s go, Taylor’s latest comes close to being an irredeemable misfire, Blunt’s impressive performance the single saving grace that keeps it from going off the rails completely.

Film Rating: 1½ (out of 4)