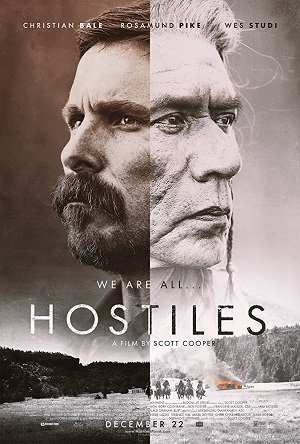

Hostiles a Cold, Brutally Complex Revisionist Western By Sara Michelle Fetters

In a remote corner of New Mexico sits Fort Berringer, a prison outpost housing Native prisoners, the most notable being dying Northern Cheyenne war chief Yellow Hawk (Wes Studi), a man who in his day played bloody games of cat and mouse with the U.S. Cavalry on a regular basis. It is 1892, and with the wounds of the Civil War still fresh in every soldier’s mind, making peace with the past isn’t something war hero and noted Indian fighter Captain Joseph Blocker (Christian Bale) is keen on accomplishing as he nears retirement. Yet, he is the one assigned the task of doing just that, his commanding officer Col. Abraham Biggs (Stephen Lang) ordering him to escort Yellow Hawk and his family to his Cheyenne homeland in Montana so that the war chief can be laid to rest in the land of his ancestors and given the respect in death he’s spent his life fighting for.

Assembling his best men to assist, the Calvary Captain unhappily sets out on what will likely be his final mission. Along the way to Montana, the small group comes across Rosalie Quaid (Rosamund Pike), a homesteader whose entire family, including her two young daughters and infant son, were slaughtered by a group of marauding Comanche warriors. Blocker and Yellow Hawk, two men resistant to let bygones be bygone, realize they must now work together if their small band is going to survive this perilous 1,000-mile trek to Montana. Together, they come to an understanding as they face off against assailants both anticipated and unforeseen, everything building to a final confrontation that will leave all sides bloody and bowed, the survivors forced to make sense of a new world that’s alien from any that they thought they knew before this trip began.

Scott Cooper’s Hostiles is a revisionist Western in the mold of Unforgiven, Little Big Man or The Searchers. It is an angry film, a belligerent, violent and bleakly desolate examination of xenophobia and racism that is fearless in its willingness to subvert audience expectation wherever it can. Cooper begins things with an act of terror that is beyond all imagining, the Quaid family save Rosalie all sent to an early grave with an aggressive, sadistically monstrous efficiency that’s suitably shocking. From there, the acclaimed writer/director sets up a story that on its surface is purposefully familiar: two warriors from opposite sides forced to coexist for a great purpose finding a form of mutual understanding, and maybe even friendship, by their journey’s end.

But nothing in the filmmaker’s latest goes as convention dictates. There is no purity to any member of this traveling band (save maybe one lone child), not even Rosalie, and even though after she joins them all the walls between the soldiers and their Cheyenne charges start to come down, that does not mean this grieving widow still doesn’t make choices that are as uncomforting as they are problematical. Everyone here is battling their own past, their own prejudices as they all make their way to Montana, the horrors of war still stirring inside as they attempt to rationalize past deeds with the apparently benign and selfless purpose of the trip they all now find themselves on.

At the heart of it all is the inherent racism lurking at the center of U.S. policy towards the Native population, an assumption of cultural and social supremacy that refuses to allow those fighting for the cause to see the bigger picture even when its thrust their way with all the subtly of a bullet fired from a Winchester rifle. While an understanding between Blocker and Yellow Hawk might be in the cards, that does not mean the former still does not see his former adversary’s way of life or cultural traditions to be far more primitive than his or Rosalie’s are. It allows Cooper to take things to a place where the future for one character is literally whitewashed, where the only path forward those in charge can see for the youngster is to assimilate him into their culture instead of finding other Cheyenne to raise him as their own.

Not all of the director’s points are made as well as others. The relationship between Blocker and one of his trusted Corporals (Jonathan Majors) is underdeveloped, and while I understand the filmmaker wants the audience to put the pieces of the puzzle representing the bonds the two men share on their own, it’s all so ephemeral the final scenes between the two don’t pack the sort of punch I’m sure Cooper intended. Additionally, many of the other young soldiers tasked with joining Blocker on his expedition end up as nothing more than slack-jawed, baby-faced cannon fodder, the likes of Timothée Chalamet and Jesse Plemons all but wasted.

But other subplots work beautifully, not the least of which is an ongoing discussion between Blocker and his grizzled Master Sergeant (Rory Cochrane) over what should be the cost for all the violence they’ve seen and all the death they themselves have had a hand in delivering unto guilty and innocent alike. The actor’s performance is a thing of poetic melancholy, the weight his character feels from the morally reprehensible things he’s done in his life oozing from every pore like rain splashing off of a faded cowboy hat. Where the Master Sergeant ends up isn’t so much a surprise as it is a heartbreaking denouement to a life that can no longer find purpose in continuing to follow the orders he’s so diligently followed for his entire life, Cochrane’s pain coming from a place so personal it’s destructive potential is without measure.

Bale and Pike are extraordinary, the latter’s breakdown as she determines to bury her children on her own sending me into a tearful fit I never did quite recover from for the remainder of the film’s 133-minute running time. There’s also a nice, albeit brief, appearance by Ben Foster during the story’s middle act that’s ruggedly disturbed in its maniacal intricacy, the truths his character speaks dripping with a poisonous venom that’s as repulsive as it is toxic. A special note should also be made of Studi’s understated work as Yellow Hawk, the veteran character actor delivering a superlative turn that ranks up there with his best work as the Magua in 1992’a Last of the Mohicans.

Cooper’s last three features Black Mass, Out of the Furnace or Crazy Heart weren’t exactly easy sells to a general audience, but no matter how one ended up feeling about them breaking each one down into an easily digestible synopsis isn’t particularly difficult. The same cannot be said about Hostiles. Its myriad of layers and moral ambiguities aren’t sitting right there at the surface waiting to be explored. They’re deep down, resting in the muck and mire of a human condition that hasn’t evolved near as much over the past few centuries as many would like to believe. It isn’t an easy sit, the end resolution a cultural demolition that, no matter how pure the intentions of the survivors might be, could prove to be even more heinous than the violence they, their compatriots and those standing against them all faced in a cold, lonely wilderness where every step could be someone’s last.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)