Latest Ben-Hur an Epic Failure

When it was announced as going into production just over a year or so ago, I admit I had strong reservations that Paramount Pictures’ ambitious, $100-million reworking of Lew Wallace’s novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ was a good idea. Not because I feel like either of the two best known previous versions, the robust 1925 silent adaptation or William Wyler’s epic, 1959 Oscar-winner with Charlton Heston, are unassailable classics, although they are close, but more because I couldn’t imagine the sensibilities of the film’s two primary producers and their chosen director to mesh.

It was just hard to fathom how Roma Downey and Mark Burnett, the minds behind Son of God, Woodlawn and the epic miniseries “The Bible,” would coexist with Timur Bekmambetov, the Russian filmmaker behind carnage-filled, cartoonish actioners like Wanted, Night Watch and Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter. While the producers specialize in faith-based stories that wear their Bible-based religiosity as a badge of honor, the director is a flashy, go-for-broke anarchist who never met a flashy, CGI-amplified visual he didn’t want to embrace. As fits go, this didn’t seem like all that great of one, and while I hoped it would all work out for the best pardon me if I had serious doubts that this was possible.

I honestly didn’t want to be proven right, because a streamlined, more forceful interpretation of Wallace’s source material isn’t the worst idea. More, casting up-and-comers Jack Huston as Jewish Prince Judah Ben-Hur and Toby Kebbell as his Roman brother-turned-adversary Messala Severus sounded like a stroke of genius. After all, the two actors have been incredibly strong in a variety of motion pictures, Huston most notably in American Hustle and Kill Your Darlings, Kebbell in full motion capture regalia in Dawn of the Planet of the Apes and Warcraft. Figure in a script by Oscar-winner John Ridley (12 Years a Slave) and Keith R. Clarke (The Way Back) maybe I had no reason to be nervous, the pieces certainly in place for a solid adaptation just as long as the sensibilities of the producers and of the directors could find some way to happily coexist.

To say they do not is likely one of the year’s major understatements, while to admit facets that should have been strong, namely the screenplay and the performances of the two stars, are massively underwhelming has to be an equally large disappointment. This new version of Ben-Hur is consistently at war with itself, a tonal nightmare of didactic faith-based melodramatic drivel coupled with over-edited, nonsensical action poppycock that helps make the movie nothing short of an out-and-out disaster.

The story remains more or less the same. Jew Judah Ben-Hur is betrayed by his adopted Roman brother Messala Severus, charged for an attack against Pontius Pilate (Pilou Asbæk) he had nothing to do with, survives five years as a galley slave, believing the entire time his mother (Ayelet Zurer) and sister (Sofia Black-D’Elia) were crucified. Returning to the city of his birth, he is aided by the mysterious Ilderim (Morgan Freeman) and briefly reunited with his selfless wife Esther (Nazanin Boniadi). Most of all, though, he is gifted the opportunity to face Messala in a no-holds-barred chariot race with all of Jerusalem watching, going after his vengeance even as a lowly carpenter-turned-messiah (Rodrigo Santoro) preaches forgiveness to ever-growing masses.

Ben-Hur is a passive and altogether a ineffectual oaf right, this giving Huston precious little to do or play. Worse, the script, even after he’s met with unimaginable hardship and tragedy, for some gosh darn reason keeps him that way. He’s gruff, sure, and not without impressive survival instincts, but as a man who is the captain of his own story Ben-Hur feels more driven by narrative necessities than he does a single thing innately human or authentic. His transformation is a facile, melodramatic one, completing its arc in a rudimentary way that is never interesting and even less emotionally effective.

As far Messala, Kebbell has a tiny bit more to do but not enough to make the movie worth sitting through all the way until the end. There is no nuance as far as his relationship with Ben-Hur or his family is concerned. Instead, it’s all heavy-handed drivel that plays on the viewer’s basest emotional sympathies, never progressing any further than it needs to in order to get the point across that Messala’s coveting of what his brother has is bad for him both physically and spiritually. If the metaphors were obvious in Wallace’s book, not to mention in all previous adaptations, they’re even more noticeable here, the film going out of its way to shove them down the viewer’s throat, thus negating their inherent power to the point of irrelevance.

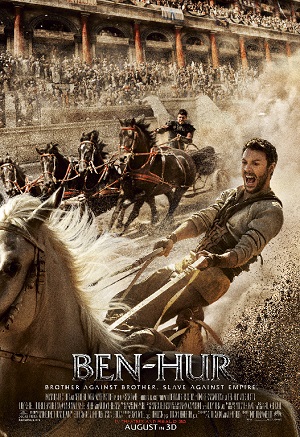

None of which would matter if Bekmambetov could have pulled off the action scenes, most importantly the central chariot race everything is building to. But in a quest to best what Wyler pulled off in ‘59, not too surprisingly the director slathers things in computer-aided effects that are far too obvious for their own good. On top of that, he and his team of editors (three are credited, all of whom have either been nominated for or won Academy Awards) have chopped the sequence up to the point of incoherence. There is no energy. There is no emotion. There’s just a bunch of pensive, sweaty looks from Huston coupled with barks of instruction from Freeman, this all-important grudge match between Ben-Hur and Messala has having impact, none whatsoever.

The one thing the director does get right is a sea battle between the Romans and the Greeks during Ben-Hur’s time as a galley slave. Seen almost entirely through the small windows in the bowels of the ship, this sequence has real tension, the energy that pulsates through every stroke the sad, lost souls rowing for their lives take coming through with intimate precision. But even this sequence doesn’t end up working near as well as it could have, Bekmambetov unable to hold himself in check, ultimately allowing the cartoonish visuals to transform things into nothing short of a video game cut scene.

Then there is the theological aspect. Just looking at the ‘59 version, no one would ever accuse Wyler’s film of being subtle as it pertains to the story of Jesus and his crucifixion that runs parallel to Ben-Hur’s quest for revenge. But the power that film has is in its brevity, its simplicity, and that’s an aspect this version does not emulate. Much like Downey and Burnett’s other religiously themed efforts, the pair thrust their dogmatic point-of-view down the viewer’s throat, and as relaxed and effective as Santoro’s performance might otherwise be, the way he and his character are utilized are so egregiously exaggerated all his work ends up going for naught.

I honestly did want this new Ben-Hur to work. The ‘59 version, for all its plusses, isn’t nearly as perfect as its classic status would lead most to believe, and other than the chariot race sequence, rightly considered one of the greatest action sequences ever filmed, there’s plenty that could have been improved upon. But the combination of Downey, Burnett and Bekmambetov just isn’t trio to make it happen, and as stories of the Christ are concerned this is one I highly doubt will see any sort of resurrection at any point in the foreseeable future.

Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 1½ (out of 4)