“Certain Women” – Interview with Kelly Reichardt

by Sara Michelle Fetters - October 26th, 2016 - Interviews

Everything is Connected

Kelly Reichardt Finds Inspiration in Isolation with Certain Women

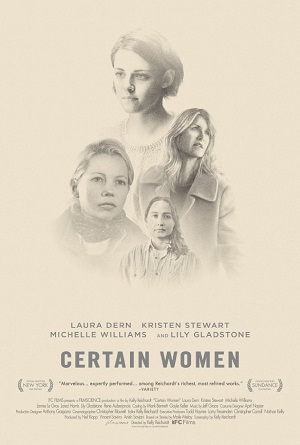

Based on the short stories of Montana author Maile Meloy, writer/director Kelly Reichardt‘s latest understated drama Certain Women is a revelatory exercise in cinematic minimalism. A three-prong story following four women – lawyer Laura (Laura Dern), businesswoman, wife and mother Gina (Michelle Williams), law student Beth (Kristen Stewart) and rancher Jaime (Lily Gladstone) – as they go about their day-to-day lives, the movie is an intimate journey into the human condition. More than that, though, it is a story about companionship and community, a heartfelt aria to finding hope in the drudgery of the familiar, and as such resonated with me on a deeply personal level that left me virtually in awe.

“The characters,” Reichardt exclaims, talking about Meloy’s stories and what it was about them that initially captured her attention, “they are so rich. I was instantly drawn to them. I loved the missed opportunities to connect and then the accidental connections that happen between people who you do not think would happen. All of that, but also the way they all fit inside their environment. It’s great, and there are so many layers hidden there waiting to be discovered. Also, in the final story, in Beth and Jamie’s story, just the idea of watching someone do their chores. I enjoy that. It’s something that’s always fascinated me.”

When looking at many of the director’s previous films, most notably Old Joy and the magnificent Wendy and Lucy, it’s easy to surmise that Reichardt is fascinated by the small things, that she adores minutia, unafraid to show her characters doing the most mundane of activities in order to dig deeper into the core of who they truly are. “I love minutia?” she asks with a laugh. “I can’t say I’ve heard that before.

“But you might be right. I think it’s just that I like giving my characters things to do. Cars to drive. Cows to work with. Chores to do. I think it can be freeing, because it gives you so much to concentrate on. You can get across who the character is through their whole body, their physicality and how they sit inside the landscape. You need to get an idea of the world that exists outside of the realm of the dialogue, find additional facets that help reveal who they are. Are they capable? Are they isolated? Are they vulnerable? This can all come through by where [the character] is inside the frame and what it is they are doing. It’s just good, challenging stuff, and I like to let my characters experience all of it.”

As far as challenges were concerned, the biggest one was trying to figure out which of the author’s tales to focus on inside the film, tests the filmmaker was eager and excited to tackle. “In Maile’s original story, the rancher, Jamie, is a young boy,” says Reichardt, “so I did make a number of changes during the script writing process. But Maile was brave and generous, letting me just go my own way, let me screw around with her stories, which admittedly at times led to some really bad drafts. Which was good, because she also allowed me the freedom to switch out one story for another, to play with how each one would eventually connect to the other, and I can’t thank her enough for that. So it took a while to figure out how all of this would fit together, and some that took going down to Montana so I could understand that environment for myself.”

Like all of Reichardt’s films, said environment is a major player in Certain Women, becoming a pivotal fifth character as the story progresses towards its conclusion. Yet, for fans of the director, it is admittedly disconcerting to see her working on a story not co-written with Jon Raymond and set inside the Oregon wilderness. “I know! Right?” she exclaims with a chuckle. “It was weird for me, too. But Jon was working on a new novel, and he wanted to finish that so I started looked for stories that were not derived in Oregon to stay out of his hair. Maile’s stories are all set in Montana, and I was ready to try a new landscape and thought I should challenge myself.”

“It’s funny how the landscape can really be inspiring and can make you feel isolated, sometimes all in the confines of the same day,” expounds Reichardt. “I’m in New York City all the time, and I’m constantly like, what a hole, why am I here? But then something amazing will happen and I’m like, this is the greatest place in the world! I can’t imagine being anywhere else. And you’re having these feelings because suddenly all the streetlights are going in your direction and that’s why you’re feeling that way; it can be that simple.

“In this case, being in Montana, it was the first time I was living in a place that was entirely landlocked. You’re seeing these mountain ranges that completely surround the area and, they’re beautiful, but they also isolate you, sort of wrap you in. But it’s also just the pace of how people move there. It’s a real difference. I ended up becoming attached to the place more than I thought I would, I have to say. Also, once I found that ranch, everything else, all the visuals in the film, they sort of sprouted out from there. Getting into the rhythm of working with that ranch owner, getting to know her and her husband, how all the animals were attached there, all of that helped me get really connected to the people and the place. Once you get your daily routine down in a place that informs everything else. I think you can see the good, the bad and all the beautiful in-between when watching the film. At least, I hope you can.”

Turning back to the film’s structure, one of the more intriguing components is how delicate each of the three stories connects one to the other. “That was always one of the big ongoing challenges,” she admits. “How do you find the points to connect or, just as importantly, when not to connect, one story to another one, that really was one of the biggest challenges we faced. There was a lot of trial and error involved, not just while writing the script, but also while filming and in the editing room as well. Instead of plot driving these women together it became more about the sound design. The idea that the sound of the train would give you an idea of where one character is in relation to another one. What was playing on the radio. Stuff like that. Stuff you almost don’t even realize is there.

“Sound is everything. Sound is a lot of the game. And I ended up getting really lucky with my sound team here, because this was all on location, and it was super, super windy for much of the shoot. Every circumstance was such a challenge, and I kept expecting them to tell me that we couldn’t shoot because of the conditions. But none of that was ever said. Not once. I’m really grateful to all of them. They did a masterful job.”

As for what audiences get out of Certain Women, the filmmaker is refreshingly succinct. “I just hope the movie gets seen,” says Reichardt matter-of-factly. “There are so many films out there right now, so many good ones, so many that even I’d like to run and go and see, so I do hope they make the time to go see this one. I do hope that audiences, when they see it, I hope they understand and appreciate the concept, and I’d be very happy if they make up their own mind as to what has been going on and what it all has been about. But, I do hope, in light of all the hostility in our world right now, that people see something about community, about togetherness and about women, that they haven’t thought about in a little while, and that they see how we are all connected even if we don’t realize it. I want us all to be looking out for one another.”

– Interview reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle