Bigelow’s Detroit a Historical Wake Up Call

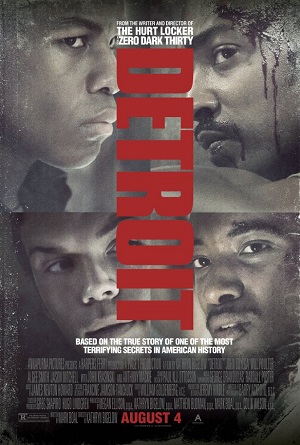

There’s a lot to unpack as it concerns director Kathryn Bigelow and writer Mark Boal’s Detroit, and writing a coherent review about the film feels almost impossible. This is the type of motion picture that needs more than a few days to mull over, its layers, ideas, concepts and themes one that live and breathe in ways that are decidedly multifaceted and bruising in their visceral complexity. Make no mistake, much like the pair’s previous two political dramas, the Oscar-winning The Hurt Locker and the haunting Zero Dark Thirty, this one will be discussed, debated and dissected for years to come, and considering the import of the story being told that’s exactly as it should be.

What can be said with instant recognition is that Bigelow is at the very top of her game. The talented filmmaker proves once again she is one of the great directorial talents working today and has been for far longer than most likely realize. There is no facet of this film that feels like it isn’t under her confidently precise control, the documentary-like verisimilitude of the storytelling nervously invigorating. With fearless abandon she looks into the heart of darkness and dissects its gritty, uncomforting nuances with unflinching exactitude. It’s a bravura showcase, one that deftly explores the parallels between one sweltering summer evening in Detroit circa 1967 and events involving police officers and unarmed suspects happening today with subtle efficiency.

After a raid goes spectacularly wrong, the city of Detroit becomes a war zone, one so intense and heated the Michigan State Police and the Michigan Army National Guard are both called in to assist the city’s Police Department in their attempts to maintain law and order. Two days into the riots, a neighborhood security guard protecting a neighborhood grocery store, Melvin Dismukes (John Boyega), and a small group of National Guard troops are startled by what they believe to be gunfire coming from the annex of the Algiers Motel. Once there, they are joined by the State Police as well as three members of the Detroit Police Department, Officer Philip Krauss (Will Poulter) quickly taking charge of the situation.

What they find are a small group of Black men, including Larry Reed (Algee Smith), the lead singer of the rising R&B group The Dramatics, his best friend Fred Temple (Jacob Latimore) and an Army Ranger (Anthony Mackie) freshly returned from fighting in Vietnam. Also in the annex are two young White women, Karen (Kaitlyn Dever) and Julie (Hannah Murray), the pair hanging out with the men at the hotel hoping to have a good time, seemingly oblivious to what is happening in the city streets. Krauss lines all of them and everyone else in this small section of the Algiers up against a wall, determined to find out where that gun is and who shot it using any and all means at his fellow officers’ disposal.

The events inside the Algiers are depicted in something close to real time, Bigelow and Boal doing their best to put viewers right up against the wall alongside Larry and the others. Yet there is nothing exploitive about what they’re showing, nothing sensationalistic or over the top. It’s a straightforward depiction, one that does not blink and also does not play favorites. It shows the horror of the situation for what it is, the casual racism and apathy happening on the part of the majority of those in law enforcement at the scene staggering in its odious nonchalance. As things spiral more and more out of control, as Krauss instructs those assisting him to play the “death game” with the suspects (a form of interrogative torture where the police pretend to murder a suspect in an adjoining room when they don’t reveal the information they are looking for), and with one innocent man already dead, there’s never a second to breathe, Bigelow allowing the all-encompassing terror to filter down into the marrow.

What’s interesting is how relaxed and free-spirited many of the introductory moments are. Even with carnage breaking out across the city, the hopes and dreams of those central to the story’s core sequences are laid bare for all to see during these early scenes. Their hopes, their dreams, the volume of life sitting in front of them, what they desire for their friends, their families and the city at large, all of it hits home. It humanizes them in a manner that’s all-encompassing, adding needed complexity to the story that makes it all the more affecting.

It all must come full circle, everything culminating in a court case involving Krauss and the other two policemen where justice is predictably going to be hard to come by. These scenes, while effectively staged, are also entirely expected, and oddly undercut slightly the power and breathless dynamism of all that’s been depicted up to that point. Yet, it is also here where the parallels between 1967 and today become the most obvious, the importance of what Bigelow and Boal are trying to say absolutely clear even for those sitting in the cheap seats and unable to put two and two together.

I cannot judge whether Bigelow was the right person to make this movie. I can only judge the film she and Boal have made. While the journalistic integrity of the piece sometimes gets a little too exact, while not all of the scenes outside of the Algiers Motel are required to hammer this story’s points home, the clear-eyed understanding the director brings to the piece is still omnipresent and emotionally affecting all the way through. Bigelow brings Detroit home, showing how this historical scar on the American Dream deserves to be far more than an abhorrent footnote. Make no mistake, there might not be a more important motion picture released this year. But it’s also so compelling, so marvelously made, so perfectly acted by all involved, the film itself is magnificent outside of its importance, and as such should be seen by all immediately.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)