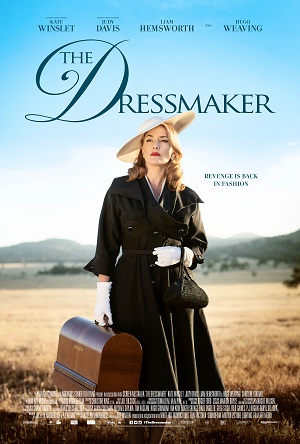

The Dressmaker (2015)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - October 7th, 2016 - Film Festivals Movie Reviews

a SIFF 2016 review

Darkly Unsettling Dressmaker an Haute Couture Hoot

Tilly Dunnage (Kate Winslet) has come home. She’s returned to the small, dusty Australian community of Dungatar ostensibly to take care of her mentally fragile, physically downtrodden mother, Molly (Judy Davis), a local eccentric who lives in a dilapidated house at the top of a hill overlooking the entire town. It is 1951, and she has been gone for almost two decades, sent away by the local authorities for what was perceived at that time as her part in a horrific tragedy that left a fellow youngster dead with a broken neck.

Now an accomplished fashion designer who has worked with some of the best designers in Paris, Tilly plans to use her skills on the snooty local populace to ferret out the truth as to what happened 20 years prior, her memories of the event spotty to say the least. What she did not count on was just how much her dressmaking skills would spin Dungatar on its head, the citizens who had once feared her and loathed her mother now rushing to the pair’s doorstep in hopes of getting a one-of-a-kind frock guaranteed to make them stand out. More, Tilly might just be falling for former childhood friend and local rugby sensation Teddy McSwiney (Liam Hemsworth), her plan to ascertain whether or not she might have played a part in another’s death keeps getting put on hold because of this.

Based on the book by Rosalie Ham, written and directed by Jocelyn Moorhouse (Proof, How to Make an American Quilt), the odd, surrealistic dark comedy The Dressmaker is very Australian. For those who loved efforts like Muriel’s Wedding or Strictly Ballroom in the 1990s, it’s pretty apparent early on this film isn’t always going to care if it goes in an entirely likable direction. This isn’t a warm or fuzzy motion picture, Moorhouse completely disinterested in following a well-traveled road. Instead, she fearlessly refuses to undercut any of the nasty stuff, and as such there are a number of twists and turns that end up being as shocking as they are distasteful.

Personally, I think that’s all well to the good. This makes both Tilly and Molly multidimensional characters the veteran actresses portraying them appear to be having a grand time inhabiting. These are women who have seen and experienced more than their fair share of strife and hardship, most of it due to the irredeemable evil that has festered and blossomed at the heart of Dungatar for what appears to be generations. Winslet and especially Davis, who is Oscar-worthy, are astonishing, navigating through seas of emotional distress overflowing in muck, the innate courageous heroism of their climactic accomplishments speaking all the louder in the end because of this.

Getting there can be a pretty crazy, uncomfortable ride, however; there’s just no denying that. The shifts in tone can be jarring, the bloodthirsty turn of events that take place during Tilly’s investigation undeniably troubling. There is a form of heartless tragedy lurking right below the surface of this story that’s close to abhorrent. Good characters jump to their doom, resulting in cataclysmic aftershocks that some find almost impossible to recover from. As for the evilest of the evil, the comeuppance they endure doesn’t always feel as commensurate to the crimes they’ve committed. And, not just against their fellow townspeople, but oftentimes also against those they supposedly love and cherish above all others, creating an emotional imbalance as far as my reactions were concerned that I found moderately unsettling.

But, like a lot of great Australian comedies of the past few decades, sweetness and light intermix freely with depravity and hardship, and in the process of doing so create a satirical wonderland that allows the people living within to feel authentic and real no matter how broad or extreme the situations themselves might become. These features, movies like The Year My Voice Broke, Flirting, Sirens or The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert, as well as the aforementioned Muriel’s Wedding and Strictly Ballroom, are all comedies, all of them going out of their way to get the viewer to laugh. But, just as clearly, as broad as they could be, they also went out of their way to make one think, as well, showcasing without hesitation the depths humanity can sometimes sink to even without meaning for it to happen.

Stuff like this isn’t for everyone, and, more to the point, it doesn’t always work, and there are times when Moorhouse loses her grip on things to the point the balance can feel frustratingly off. Not just off, but downright cruel, one particular sequence right as the final stretch begins a punch in the gut, and much like Tilly herself, I almost didn’t recover from. It’s a sequence that pulls the rug right out from underneath the audience, and, whether or not the heroine is able to enact vengeance for the wrongs committed against her, her mother and to the scant few good souls residing in Dungatar, almost isn’t worth discovering.

Only almost. Thankfully, the character dynamics are so strong, and Winslet and Davis are so gosh darn terrific, that the majority of the stuff that doesn’t sit all that well never stings nearly as much as it potentially could have otherwise. Additionally, Moorhouse, returning to the director’s chair after far too long an absence, her last film 1997’s admittedly unsuccessful, if still highly ambitious, King Lear reimagining A Thousand Acres, is in superior form, handling the majority of the changes in tone and shifts in focus rather marvelously. She also stages a number of sensational set pieces, not the least of which is Tilly’s fiery last stand, the mark she ends up making on the vilest members of the Dungatar’s citizenry downright spectacular.

While not all members of the cast make a lasting impression (poor Caroline Goodall is left out to dry something fierce), there are those that pick up the slack. Hemsworth has never been this engaged (or this undeniably sexy), delivering one of the better performances of his career up to this point. Sarah Snook’s transformation is priceless, and while her ugly duckling does become a swan, what this ends up revealing about her character’s inner nature is captivatingly divine. Best of all might just be Alison Whyte, her character potentially suffering more than anyone without ever really knowing it, her discovery at just how heinous the trick that’s played upon her has been only dwarfed by the fitting malicious glee of her response against her heretofore unknown assailant. Then there is Hugo Weaving as the town’s lone law enforcement officer, and I think it goes without saying any correlation between his performance here and his one in The Adventures of Priscilla is likely purely intentional.

If I’m being coy about whom these people are playing and their importance in the proceedings, that’s on purpose. Discovering the ins and outs of the story is what allows The Dressmaker to work near as well as it does, and for those unfamiliar with the source material (as I was) putting the pieces together is part of the film’s charm. More than that, Moorhouse’s willingness to push the envelope and dive into the darkest aspects of the tale with such macabre relish allows the emotions swirling within this maelstrom to resonate all the deeper, The Dressmaker an haute couture Aussie barnburner that’s dressed to the dark comedy nines.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)