Warm-Hearted Foster Jenkins Sings a Happy Tune

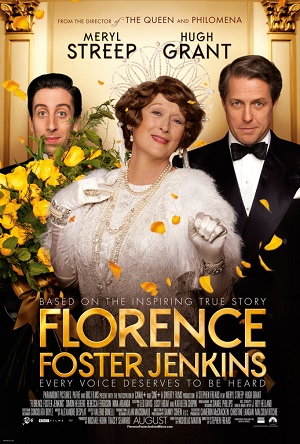

Based on a true story, director Stephen Frears’ (The Queen, Dirty Pretty Things) warm-hearted Florence Foster Jenkins is inspirational cinematic comfort food, meaning it’s a terribly difficult movie to dislike while at the same time also an almost equally tough one to embrace with any passion. A good movie, one featuring turns by Meryl Streep and Hugh Grant that are spellbinding in their all-around magnificence, it’s still awfully hard to say anything that transpires here comes as anything approaching a shock. As such, this ends up being a remarkably easy motion picture to watch and yet an equally problematical one to remember much about afterward other than the brilliance of the two stars around which everything revolves.

In 1944, aging New York City socialite, philanthropist and amateur opera singer Florence Foster Jenkins (Streep) wants to do something special for the troops who have freshly returned home after fighting in Europe and the South Pacific. Up to now, manager and faux husband St. Clair Bayfield (Grant) has done a grand job of fanning his beloved’s illusions of being a great singer, bribing critics to write kindly reviews of her shows while also making sure she performs in front of audiences who will be respond positively to her performances.

Now, however, not only is he having to break in a new pianist to accompany her, the perplexed Cosme McMoon (Simon Helberg), he also has to figure out how to schedule a showcase at Carnegie Hall. With time running short and his real wife Kathleen (Rebecca Ferguson) starting to tire of her husband’s double life, St. Clair is at his wits end as to how he’s going to pull this off. He’s instincts are to protect Florence from ridicule no matter what, knowing that by allowing her to perform in front of 3,000 strangers he can’t handpick he’ll be opening her up to just that, maybe even something worse.

You can listen to some of Florence Foster Jenkins’ recording on YouTube and, quite honestly, they’re pretty amazing. Not because they’re better than you think they’ll be but more because they’re maybe even worse than anticipated. But there’s something magical about these pieces of music history, a slice of Americana that are as beguiling as they are terrible. Listening to them, it’s easy to understand in some ways why Florence became such a New York icon during the 1940s, the fearless way in which she throws her body and soul into them close to extraordinary.

It is a credit to both Frears and to screenwriter Nicholas Martin that they are both able to understand this about the woman, embracing her uniquely selfless ferocity as her passion for music, the city she loves and men fighting for her country overseas come to the forefront of their story time and time again. This is a profile in courage John F. Kennedy would likely have applauded, and watching St. Clair do everything he can to make sure Florence’s dreams and aspirations are nurtured and allowed to blossom no matter what can’t help but soften even the hardest heart.

But even not knowing a thing about the people involved in this story before the film began, I still had every beat of this tale down right from the opening frame. I was never surprised by anything that happened, even the revelation that St. Clair wasn’t really married to Florence and in fact had a real wife living on the other side of the city didn’t catch me entirely off guard. There was never any question how all of this was going to end up, and if truth really is stranger than fiction this is one instance where that axiom felt far more contrived and mechanically scripted than it typically does.

Yet I wasn’t kidding when I said Streep and Grant were magnificent. The two deliver, so much so if awards recognition were to come either of their respective ways in the latter portion of this year I’d not complain one single little bit. They are spellbinding, both separately and as a duo, each building their characters in ways that are genuine, heartfelt and melodiously pure. Streep and Grant navigate the more melodramatic portions with rapturous eloquence while also bringing to life less fleshed out aspects of Florence and St. Clair the script only has the time to hint at. In doing so they put the movie on their shoulders, carrying it to a place of happy ebullience with joyful ease.

Frears could direct a story like this in his sleep, and while he’s not digging as deeply as he did with 2013’s somewhat similarly themed Philomena comparisons between this film and that aren’t altogether out of place. He’s also assembling a strong supporting cast to work alongside his two stars, Ferguson, Helberg and a sensationally effervescent Nina Arianda, channeling Judy Holliday as a smart-alecky trophy wife who’s far more intelligent, and compassionate, than she initially appears, all delivering the goods when asked to. None of which makes Florence Foster Jenkins itself extraordinary, just entertaining, and in a summer season where so many movies have underwhelmed that’s one tune I’m happy to hum no matter how overly familiar it ends up proving to be.

Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3 (out of 4)