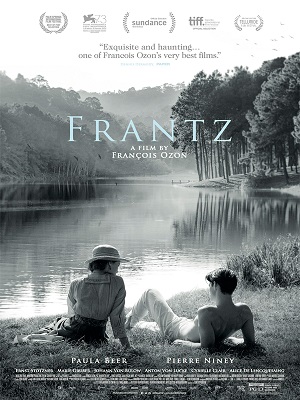

Post-War Grief Gives Way to Newfound Hope in Ozon’s Spellbinding Frantz

World War I has come to its bloody conclusion, and young Anna (Paula Beer) mourns the loss of her fiancé Frantz (Anton von Lucke), killed fighting the French in a lonely trench on a remote battlefield far she will likely never visit. She lives with her slain beloved’s parents Doktor Hans Hoffmeister (Ernst Stötzner) and his devoted wife Magda (Marie Gruber), each of them attempting to grieve in their own way each and every day.

On one of her frequent trips to the church graveyard, Anna stumbles upon a shy Frenchman also there to pay his respects. After some dogged determination to learn who he is, turns out the young man, Adrien (Pierre Niney), himself a military veteran, knew Frantz back in Paris before the war. Intially worried as to how they’ll respond to him, Anna brings Adrien to meet Doktor Hoffmeister and Magda, and while the group’s early conversations are justifiably stilted, after awhile the longing for information and the need to have a concrete connection to their son takes hold of the parents. Much to the bewilderment to the town at large, this strange quartet forms a strong friendship, all of it built on each individual’s memories as they pertain to Frantz.

French auteur François Ozon (In the House, Swimming Pool), working in collaboration with Philippe Piazzo, presents Frantz, an adaptation of Ernst Lubitsch’s 1932 classic Broken Lullaby, and in the process crafts a distinctly feminine version of the story that is beautifully refined and intimately profound. Telling things from Anna’s point-of-view, allowing cinematographer Pascal Marti (The New Girlfriend) to paint with both vibrant, electrifying color and shrouded, passionately melancholic black and white, this gorgeous stunner held me spellbound first frame to last, the film a piece of pure cinematic wonderment audiences eager for something substantive should make the effort to see.

For those new to the story, and considering Lubitsch’s film isn’t exactly easy to see or find that’s going to be just about everyone, things regarding Anna, Adrien and the Hoffmeisters are never what they appear to be. But there is nothing untoward going on, no one involved in this emotional mélange wanting to cause undue heartache or trauma to anyone else they are conversing with. Truth becomes lie, fiction becomes fact, grief is assuaged and forgiveness is sought. Through it all, Anna must discover who she is, what she wants from life and what she is willing to do to carry on now that Frantz is no longer physically with her, where she is willing to go to find answers to these questions the palpitating heart beating at the center of Ozon and Piazzo’s moving adaptation.

I’m being coy for a reason. The journey Anna takes is delicately nuanced, and while it doesn’t take a rocket scientist to realize Adrien isn’t who he proclaims to be, his knowledge of Frantz is so richly extensive it’s easy to miss all the hints Ozon craftily drops as to what is going. Even so, the revelations, when they come, happen with a matter-of-fact certainty that’s startling, the beauty of the truth being laid bare no matter what the consequences a breathless summation to the film’s first hour. The two actors, Beer and Niney, are extraordinary during this moment, the way both communicate on a wavelength brimming with guilt, recrimination, fear, heartache and understanding something hauntingly special.

What’s amazing is that this is only the film’s halfway point, Ozon dropping the hammer on what’s going on but doing so in a way that allows the remainder of the story to naturalistically flow from there. Anna, for reasons having to do with her crippling affection for Frantz as well as her selfless love for the Hoffmeisters, becomes the mirror image of the stranger who came from France and helped ease the pain of two parents who never imagined their grief could be assuaged. She continues a lie because she knows it gives them comfort, goings so far to journey to Paris herself in order to learn more about Adrien and to find out how he’s doing after unburdening himself of such a catastrophic secret.

Newcomer Beer is astonishing. Ozon keeps her front and center in practically every scene. Her transformation is key. The way Anna comes to understand the repercussions of this war, the singular human destruction that has taken place on such an unimaginable scale unlike anything the world had ever seen up to that point, it forces her out of that personal bubble of grief, the young woman’s eyes opening more clearly than they ever have before. Beer travels between a number of different emotional layers with graceful majesty, each second a revolving door that helps increase understanding of the woman’s pain as well as the ways she might hopefully be able to deal with it.

Ozon takes no sides and also doesn’t pull punches. There are no easy answers as everyone has been dealt a heavy blow by the war and all of them are having trouble figuring out how to cope now that it has come to an end. Peace proves to be every bit as contentious and belligerent as the conflict was, and even with bombs no longer dropping from the sky and with no more bullets whizzing through the air, none of that means people are able to go back to the lives they knew before having survived events as earth-shattering as these.

But what does that journey feel like? What are the difficulties, for soldier and civilian alike, to find a way to carry on and look at life again as if it is full of possibility and wonder and not walk under a cloud of despair, grief and regret? This is the road Anna is on, Ozon tracking her as she deals with so many conflicting emotions and desires, all of them augmented to varying degrees by the loss of Frantz, her relationship with his parents and the introduction of Adrien into her life.

It’s miraculous, there’s no other word for it. The emotions Ozon deftly has his characters transition through are amplified by precise bursts of color, these transitions signifying the softening of grief and the remembrance that life’s promise still exists even in the petrifying crucible of post-war reconstruction. By the time it comes to an end, Frantz has made a permanent imprint, the hope for a better tomorrow after a cataclysmic yesterday striking chords of promise that make even the harshest of injuries feel as if they someday can be healed.

Film Rating: 4 (out of 4)