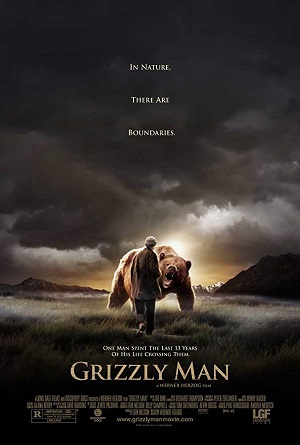

Grizzly Man (2005)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - August 12th, 2005 - Four-Star Corner Movie Reviews

Herzog’s Man a Grizzly Nature Hike

Timothy Treadwell dedicated his life to the preservation of bears. Particularly the Grizzly Bear, founding the nonprofit organization Grizzly People and writing a book with good friend Jewel Palovak about the best ways to ensure the animal’s survival. He also chose to live with the bears, spending thirteen consecutive summers camping in Alaska’s Katmai National Park and Reserve to study and protect them. Treadwell would have probably kept on doing this forever, but in October of 2003 one of Timothy’s prized Grizzlies had other ideas, choosing instead to treat the environmentalist as a mid-afternoon snack.

So was Treadwell a fearless do-gooder with the Grizzly’s best interests at heart? Or was he a crazed lunatic who put his own life and the lives he brought with him into the wilderness in danger, finally resulting in, not only his own death and the tragic demise of girlfriend Anie Huguenard, but also the killing of one of the bears he swore to protect? It’s hard to say, but by using the videotapes of the last six years of Treadwell’s expeditions and by interviewing many who knew him master filmmaker Werner Herzog (Fitzcarraldo) attempts to find out. The result is Grizzly Man, an engrossing documentary chronicling the reckless genius that compelled this determined man to live within the confines of the dangerously seductive Alaskan wilderness.

The glory of this doc is Herzog’s brutal honesty in probing the naturalist’s legacy while yet still crafting a living record that allows the viewer to make up their own mind as to what Treadwell’s actions and subsequent death ultimately mean. While the director as always isn’t afraid to add his own input, insights or opinions he never preaches as if they were the gospel. It is a deft, evenhanded film that revels in the picturesque majesty of the images Treadwell captured before he was killed by the bears, and even if his focus was a bit misguided the footage he brought back with him still cannot help but inspire.

It is, in fact, these five years of documentation that makes the picture magnificent. Treadwell captured Grizzly Bears like no other on Earth had before, scenes of the creatures hunting, playing, fighting and just going about the daily drudgery of living life caught just mere feet away from the intrepid cameraman. Some of his stuff blew my mind, the naturalist collecting images so extraordinarily beautiful it’s enough to stop the heart and still the breath.

Even more remarkable are the images of Treadwell himself. Turning the camera on himself, these scenes of the bear enthusiast are astounding. Through them we see firsthand his almost religious love for the animals and his passion for giving every ounce of himself to ensure their survival. We also see Treadwell’s complicated human side, the man’s vanity, pride, rage, paranoia and profound loneliness coming out again and again as he re-shoots himself over and over again like Cecile B. DeMille until he gets the moment perfect.

Additionally, Herzog takes real joy in spotlighting Treadwell’s gifts as a charming liar. Case in point? He claimed to be from Australia when he was really raised in middle class New York. He says the bears are hunted by poachers within the nature preserve while the only bear to die by human hands on the reserve is the one that ate him and his girlfriend. Herzog makes sure Treadwell remains an astonishingly charismatic enigma noting that he was a drug addict, a struggling actor, a sometimes school teacher and an impassioned champion for the environment. He was all of these things and more, the activist both larger than life and tiny as a flea, concealing the person he really was from prying eyes virtually no one until Herzog bothered to take the time to try and see.

Pouring through hundreds of hours of videotape the director somehow skims things down to a brisk 100 minutes or so of footage, letting Treadwell’s visuals tell the story for him. My favorite bits include a family of foxes who befriends him, all of them becoming sort of a surrogate Greek Chorus for him to belt out his frustrations, discuss the state of humankind and express all his love of the wilderness to. There’s also a great scene of Treadwell begging for rain, shouting at God, Allah, Jesus and, “the Hindu floaty thing,” to bring on some much-needed storm showers.

But the most incredible footage might just be what Herzog chooses not to show. Treadwell recorded, obviously quite by accident, his own death, the lens cap on but the audio recording all of his last gasps, shrieks, screams and yells as he tried in vain to scare the hungry bear away and save the girl he professed to love. We hear none of this, however, Herzog instead focusing only upon his own reactions to the recording upon hearing it for the first and supposedly only time.

Whether or not this footage should have been included in the picture for the audience to hear can be debated (personally, I had no wish to hear any of it), but the power of watching the director squirm in his chair and seeing his facial contractions as he reacts to it is still not for the squeamish. It is a devastating moment, Herzog handing back the video camera to a thoroughly shaken Palovak and imploring her to never, ever listen to the horrors contained upon the tape.

Hero or idiot, Treadwell’s love for the bears is still irrefutable. By fearlessly examining the man warts and all, Herzog has fashioned a nature documentary unlike any I’ve I think I have ever seen. I can’t say it is perfect, and not all of the questions it raises are answered, but the same can unquestionably be said about the man it chronicles, Grizzly Man the type of human adventure that makes going into the cinematic wilderness fascinatingly worthwhile.

Film Rating: 4 (out of 4)