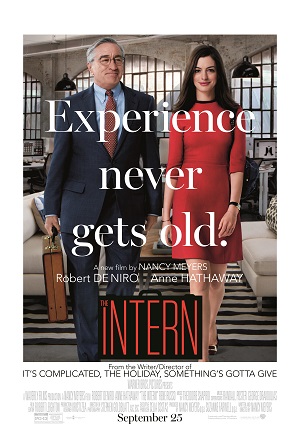

Prehistoric, Patriarchal Intern Unworthy of a Permanent Position

Ben Whittaker (Robert De Niro) is a 70-year-old widower who has been trying to make the most of his retirement, but all this pointless inactivity is starting to get the better of him. Things change when he applies for an internship at an online clothing retailer that’s been doing rather well but is also looking to find ways to diversify its twenty-something workforce and learns he’s been selected for the position. Not only that, he’s working directly for the CEO entrepreneur that started the business, Jules Ostin (Anne Hathaway), seeing right away the kind-hearted businesswoman could use a hand even if she’s loathe to admit it.

Nancy Meyers’ (It’s Complicated, The Holiday) latest female-driven confectionary comedy The Intern made me angry. Angry, because for a large portion of its 121-minute running time I was enjoying myself immensely until the point I suddenly no longer was. Angry, because it presents a strong, intelligent, fiercely-independent lead character who’s a savvy businesswoman and loving mother and then unceremoniously throws her under a misogynistic, patriarchal bus for no real reason that I could surmise. Angry, because this should have been a good movie, both De Niro and Hathaway, both of whom are terrific, deserving of so much more than Meyers ultimately gifted them.

The basic thrust of the film is that Jules, wanting to make her own mark, understanding her business better than just about anyone (it’s an e-commerce fashion website the promises to give the customer “the perfect fit” no matter what), is under pressure from her investors to hire a seasoned CEO to take over the day-to-day running of things. She doesn’t want to do it, lose control in this way, but pressure from both her partners as well as from home place her into a state of almost constant indecision, thus making this prime territory for Ben to add some fatherly input whenever the opportunity arises.

It’s nice enough, politely cordial a majority of the time, and much like most Meyers comedies it rarely overplays its hand or pushes the issue to the point of annoyance or discomfort. I liked the way she allows De Niro to build his character, and while he’s not too different than the elder statesmen she crafted for Jack Nicholson in Something’s Gotta Give or Steve Martin in It’s Complicated, Ben is still just multifaceted enough to make hanging out with him hardly a chore. His relationship with Jules is a strong one, especially early on, their growing friendship having a beguiling spunk and sparkle to it that’s positively divine.

But things start to unravel around the midpoint, Hathaway forced to turn on the eye faucets as if she were still going after that Oscar she already won for playing the tragically doomed Fantine in 2012’s Les Misérables. She allows herself to be judged by the men around her (as well as more than a few of the women), all in search of their approval even though she’s done more with her life in a few months than the majority accomplish in an entire lifetime. On top of that, even in a year when there are two viable female candidates for the Presidency of the United States every single person she agrees to interview for the CEO position just happens to be a guy, the fact it never even occurs to her to add a single woman to the list of potentials rather baffling.

The wheels don’t completely fall off, however, until the final act. It’s at this point secrets involving those at home reveal themselves, emails to intrusive, condescending relatives are sent and a decision on whether or not a CEO will indeed be hired all come to the forefront, the overall weight enormous. Jules, so in control, so in charge, all of the sudden she can’t make a decision to save her life, and it’s not only up to Ben to decide things for her but also another benefactor I’d rather not name. Problem is, the latter has done something beyond heinous, driven a stake through this smart woman’s heart with unimaginable force, the fact she’d even be open to hear and process all he says as if it were gospel before he even makes an attempt to apologize for his misdeeds well beyond me.

I’m not saying forgiveness cannot be found. I’m also not saying decent advice shouldn’t be listened to. But the manner in which all of this takes place in the final few minutes is something extraordinary, and the fact Jules is so willing to fall back into the arms of someone who wronged her so personally is beyond reprehensible. Yet, worse than all of this, making me more furious than just about anything, it is the fact she has to be told what to do by the men surrounding her in the first place, a slap in the face to both the character as well as the audience that had grown to love her over the course of the majority of the film.

There’s so much more I could say, but in honesty I find myself thinking that’s enough. The Intern has great potential, De Niro and Hathaway making a terrific team deserving of a better script. But Meyers lets them all down, and that includes herself, unleashing a cavalcade of old ideas so prehistoric they went out of date around the same time women won the right to vote, making the film a bad candidate unworthy of a permanent position.

Film Rating: 2 (out of 4)