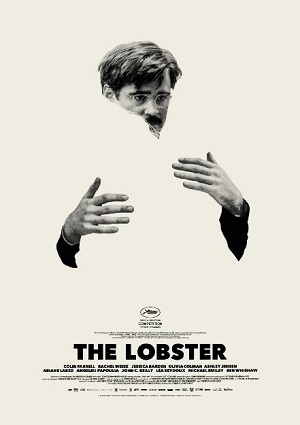

Surrealistic Stunner The Lobster a Sensory Feast

In a world not unlike our own, singles trying to eke out a living on their own are arrested by the police and sent to The Hotel, a five-star estate overflowing in amenities. They are tasked with finding a mate, someone it is assumed, or at least hoped, they will subsequently spend the remainder of their life with. Unless they earn extra time, usually by hunting fugitive singles hiding in an adjacent forest, after 45 days it is determined they will not find a partner, and as such are transformed into an animal of their choice and sent out into the wild to begin their lives anew.

Recently divorced, David (Colin Farrell) has arrived at The Hotel. After settling in, he quickly makes the acquaintance of a man with a lisp (John C. Reilly) and another sporting a rather significant limp (Ben Whishaw). The Hotel Manager (Olivia Colman) believes David has what it takes to find a match, particularly proud of him when he seems to hit it off with a seemingly heartless woman (Angeliki Papoulia) who has managed to remain at The Hotel almost four-times longer than her allotted 45 days thanks in large part to her skill hunting singles in the forest. He’s also fond of a young woman prone to nosebleeds (Jessica Barden) but his limping friend feigns a similar ailment in order to get close to her, the sight of the two of them together causing David to feel pangs of anger he doesn’t believe either deserve.

All of this is only the beginning as it pertains to Greek director Yorgos Lanthimos’ (Dogtooth) odd, enchantingly bizarre and bracingly surreal The Lobster, a Kafka-meets-Kubrick romantic allegory that puts society under a kind of microscopic glare that is as entirely unique as it is uncomfortably original. Working once again with co-screenwriter Efthymis Filippou (Alps), the pair have dreamt up an otherworldly scenario I can barely comprehend let alone try to describe, that above synopsis barely hinting at the imaginative chaos this film proudly celebrates.

There is a detached indifference to the ins and out of the mating process, a clinical exactitude that almost requires potential couples share all the same qualities both mental and physical. This depiction is then mirrored in many ways by those who choose to live unattached, singles practically forced to remain emotionally dispassionate or risk being ostracized and physically mutilated by fellow non-marrieds hiding in the forest alongside them. In both instances, love either isn’t a consideration for coupling or is disallowed entirely, giving things an almost Orwellian edge that’s impossible to miss.

As impressive as all of this might be, The Lobster isn’t an easy movie to like. It’s purposefully distancing, conversations taking place with a stilted exactitude that’s initially off-putting, while the crazed nature of the dystopian scenario itself keeps the viewer at arm’s length almost as if the filmmakers were daring them to try and embrace their motion picture knowing doing so is practically ridiculous. These are archetypes, person-sized caricatures being sent forth to navigate a type of maze where the entrance is impassible and the exit is nothing short of a nightmare. Worse, freedom comes with a price, one that is almost as bad as being stuck in that cheese-filled mousetrap was in the first place.

And yet, the level of emotion as things build to their conclusion is extraordinary. In a second act twist, David ends up in the forest, attempts to survive alongside the rebels, and in the process encounters a kindred spirit (Rachel Weisz) he’s not allowed to fall for on pain of emasculation. Yet their romance, guided by distance, tinged with regret, aching with subtle glancing caresses and the occasional freshly skinned rabbit, has a punch to it that’s startling, building in intimate intensity as events progress. It all leads to an unfathomable form a tragedy that’s as distasteful as it is touching, these emotional opposites working in delicate concert and in doing so compose a concerto of romance and togetherness that spans the entire extent of the human condition.

Farrell is nothing short of brilliant, his brave, fearlessly raw performance containing a plethora of subtle gradations that fit in perfectly with the world Lanthimos has gone to great pains to create. He’s matched by Weisz, the intricacies of her psychological maneuverings as she clinically assesses her situation bordering on remarkable. Whishaw, Colman, Papoulia, Ariane Labed (as a secretive maid working at The Hotel) and especially a carnivorously manipulative Léa Seydoux (as the leader of the rebels living in the forest) are also superb, while Reilly brings a shaggy dog comedic weariness to his few moments that hammer home the script’s cleverer nuances rather marvelously.

It’s hard to know exactly who The Lobster is made for; all I really know is that I rather loved it. This is the type of film I’m going to watch multiple times, obsessing over every choice Lanthimos and his talented team of cinematic craftsmen made in order to see it come to life. It is a brutal evisceration of cultural conventions regarding sex, gender, romance and love, offering up so much food for thought only the animal lurking inside us all is the only one capable of lapping it up as if it were Thanksgiving dinner.

Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)