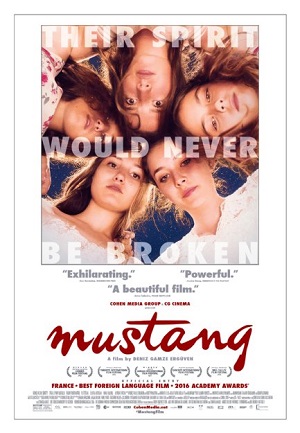

Turkish Mustang a Heartbreakingly Stunning Debut

Turkish import Mustang is so unbelievably terrific it almost doesn’t feel fair. The arrival of a major new talent in the form of director Deniz Gamze Ergüven, who also co-wrote the script with Augustine auteur Alice Winocour, the movie is a major triumph. Both a celebration of the human spirit as well as an emotional wallop as patriarchal prejudices conspire to deprive five sisters of their seemingly unbreakable familial bond, this is a remarkably prescient story that feels as if it were ripped from the headlines, it’s last moments darn near close to perfect.

As school comes to an end and summer begins, five sisters – Lale (Günes Sensoy), Nur (Doga Zeynep Doguslu), Ece (Elit Iscan), Selma (Tugba Sunguroglu) and Sonay (Ilayda Akdogan) – frolic with some local boys along the rocky shores of the beach as well as within the playful confines of an apple orchard. But their strict grandmother (Nihal G. Koldas) does not approve, and with the help of their cantankerous, fundamentalist Uncle Erol (Ayberk Pekcan), she locks them all up inside the house, refusing to listen to a single, and truthful, cry of innocence.

What transpires next is as damning an indictment of patriarchal misogyny as any I could have imagined. At the same time, it’s also a stunning feminist aria of hope and resilience that transcends the cultural divide. Turns out, the sisters’ grandmother just isn’t worried about their collective purity; she also has plans to train them all to be dutiful and devoted wives, marrying them off one by one until all are out of her hair. She wants to strip them of their individuality and crush what she sees as pointless dreams of a future constructed on their own terms, believing a woman’s place is in the home under the thumb of her man – no ifs, ands or buts about it.

The most obvious comparison here is to Sofia Coppola’s 1999 adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides, but I’m not entirely sure it’s an apt one. For one thing, this presentation is far less flowery, much less ephemeral, Ergüven eschewing the metaphorical dreamscape Coppola rhapsodically trafficked in. For another, as delightful as certain asides, subplots and escapades might become, the basic central thrust plays more like something out of a psychological horror tale recalling Polanski or Chabrol than it does a melodrama of fundamentalism run amok. Watching these girls getting stripped of their identities, seeing them battered and bludgeoned into submission, it’s all rather heartbreaking, the bonds holding them together systematically eroded until they all but disappear.

The way Ergüven and Winocour mix tragedy and hope together is sublime. The tiny revolutions the five sisters manufacture, the way they plot their escapes and attempt to hold on to the idiosyncratic hallmarks that make each of them unique, it’s all tremendous. But every high is connected to a shattering low, each sister in succession taken away and more or less sold into servitude, betrothed to men they don’t even know and expected to care for their every whim and need as if it were the most important thing life has to offer them.

There are some important surprises, the less said about them the better, the majority of which allow for a moderately hopeful vibe that somehow manages to cut through the misfortune and misery. Most of this ends up having to do with the youngest sister, Lale, beautifully portrayed by the lithe yet endearingly impetuous Sensoy. She’s the one telling this story, and also the one most likely to break away from the shackles being imposed upon her and her sisters by their grandmother and their Uncle Erol, the places she chooses to go and what she wants to experience not so much shocking as they are genuinely touching. In her, there is something of a hero aching to break free; whether or not this happens a thing Ergüven allows the viewer to decide for themselves.

Mustang isn’t without its missteps, some of the stuff involving Uncle Erol both obvious and overly sensationalistic, most often in ways the remainder of the movie seldom, if ever, is. I’m also not entirely certain what I think of Warren Ellis’ (Lawless) stripped-down score, his music at times chillingly effective and at others wildly obtrusive. Overall, though, Ergüven has delivered a debut for the ages, her film a chilling, emotionally shattering marvel I’m unlikely to forget anytime soon.

Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)