Gracefully Poetic Polina a Heartfelt Dance of Self-Discovery

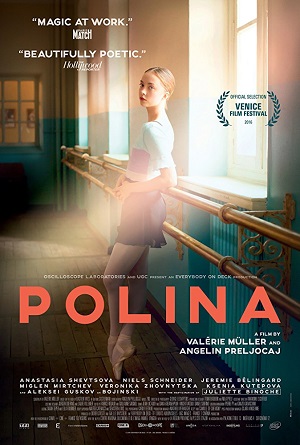

There is something about Polina that captures my imagination entirely, a poignantly fragile beauty to it that belies a sturdy heart and a will made out of iron. Based on the acclaimed graphic novel by Bastien Vivès, co-directed by filmmaker Valérie Müller and vaunted choreographer Angelin Preljocaj, the movie is a stirring tale of resilience and fortitude set in the cutthroat world of ballet and modern dance. It soars with a poetical majesty that’s spellbinding, everything building to a final sequence of events that had my emotions doing cartwheels as passion, pain and prowess all came together to produce something undeniably magnificent.

At eight-years-old, Polina (Veronika Zhovnytska) is taken by her parents to a Russian ballet school to audition for the notoriously perfectionist Bojinski (Aleksey Guskov), a well-respected instructor whose pupils have gone on to dance all over the world. While nowhere near as technically proficient as others in her group, there is something about the child that attracts Bojinski’s eye. He sees something in Polina, a ferocious determination that he might be able to mold into something glorious if this youngster is willing to work hard enough to achieve her dreams, and as such he accepts her into the school to be trained.

Years later, Polina (Anastasia Shevtsova) has excelled and Bojinski could not be prouder of his pupil. But just as she is on the verge of being accepted into the Bolshoi Ballet, the young woman is captivated by the world of contemporary modern dance. Polina eschews the Bolshoi and instead heads to Paris to study under renowned choreographer Liria Elsaj (Juliette Binoche), the two establishing an instant connection almost as if the latter has noticed something of her youthful past self in the lithe, athletic body of the technically exacting former. But for as much as they see eye-to-eye, Polina’s inability to let go, to not always seek perfection, keeps her from tapping into the emotional recesses that are key for Liria’s artistic vision to be realized, a wall building up between the two that could very well destroy the dancer’s dreams of success before they have the chance to be realized.

This is a fairly simple breakdown of the plot, but in all actuality Müller and Preljocaj’s film is far more complicated and nuanced than any brief synopsis could ever do full justice to. Character’s weave in and out of Polina’s story, including a pair of boyfriends, each of whom plays a key role in helping her make some core decisions, both good and bad; no one really staying around all that long but all making an indelible imprint that’s difficult to forget. In the end, both Bojinski and Liria are proven correct. Polina might be talented, but technical perfection can only take her so far, and until she learns why she dances and how to tap into the deep, tragic-filled well of emotions she’s loathe to take stock of she’ll never be the star both of her instructors feel she could be.

I’m hesitant to talk too much about what happens after the dancer leaves Paris, as the film’s final third is a constant stunner that held me spellbound, and while I won’t say I was surprised by where things ended up, the tears cascading down my cheeks were as genuine as they were well-deserved. Seeing Polina find herself, watching her struggle, live life and find the reason to become the dancer she worked so hard to become but do so in a manner she would never have imagined possible when she was a little girl, all of it is amazing. My heart was continually in my throat, the final dance sequence so mind-blowing my eyes came perilously close to popping right out of my head.

Shevtsova, a professional dancer who has performed with Saint Petersburg’s Mariinsky Theatre, is extraordinary as Polina. Her performance is exquisitely rigid, the young woman fearlessly not dulling the character’s sharper edges, not seeming to care one way or the other if audiences like the dancer or not. This has the effect of making her transformation during the latter stages of the film all the more powerful. Seeing Polina deal with her hardship and emotional travails, most of which she’s brought upon herself, watching her as she channels these painful experiences into her art, all of it is sensational, and it’s all because of Shevtsova that it works as well as it does.

Being unfamiliar with Vivès’s best-selling graphic novel, it’s not for me to say if the differences between it and Müller’s introspective screenplay are a big deal or not, although based on the divine beauty of the film, the way it achieves such complex realism, it seems to me this is a silly conversation. I love that Liria, even as briefly as she is around, makes such a lasting impression, Binoche bringing her to life with marvelous ingenuity. Same with Guskov as Bojinski. This man could have been a caricature, while the performance itself could have just as simply slipped into melodramatic cliché. Instead there is more to this driven taskmaster than initially meets the eye, and as such the film’s final seconds resonate with a fervent vitality that knocked me softly senseless.

The dance sequences are beyond compare, Preljocaj’s staging of them, coupled with cinematographer Georges Lechaptois’s (Disorder) stunning camerawork, just astonishing. The languid evolution of the visuals parallel Polina’s own journey as a dancer, everything culminating in a final number that is truly incredible. The profound beauty of what happens during this last modern dance ballet encapsulates everything Müller and Preljocaj have been building towards flawlessly, ultimately making Polina the type of unexpected marvel that keeps me heading back to the theatre time and time again. I love this movie. More importantly, I cannot wait to see it again.

Film Rating: 4 (out of 4)