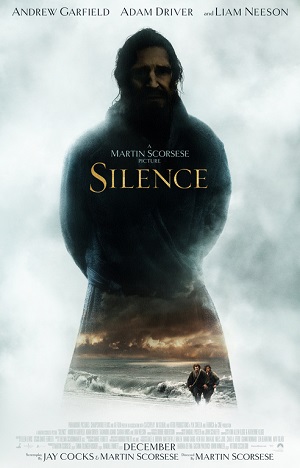

Scorsese’s Silence a Grueling Exploration of Suffering, Sacrifice and Grace

After learning that their beloved teacher and mentor Father Christovão Ferreira (Liam Neeson) may have apostatized himself – disavowed his believe in the Holy Catholic Church – while doing missionary work in Japan, Father Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) and Father Garupe (Adam Driver) beg their superior Father Valignano (Ciarán Hinds) for permission to travel from their home in Portugal to the secretive Asian country to investigate the matter. It is 1633 and the ruling Japanese Tokugawa Shogunate has outlawed Christianity thus forcing converts underground, utilizing all manner of abhorrent methods to stamp out the religion. Rodrigues and Garupe are undaunted, determined to make the perilous journey and minister to the people who share their faith, believing they will discover the truth about their beloved Father Ferreira if they are willing to journey into the unknown.

Thanks to the help of drunken expatriate Kichijiro (Yôsuke Kubozuka) whom they meet in China, the Fathers are welcomed into a small coastal village with open arms, elders Ichizo (Yoshi Oida) and Mokichi (Shin’ya Tsukamoto) pressing the pair into service with a warm smile and a selflessly loving embrace. But the Grand Inquisitor Inoue (Issei Ogata) will not be stopped, and he’s become very good at ferreting out Christians, his vengeful wrath oftentimes delivered with a knowing smile and grandfatherly wink. Rodrigues and Garupe, worried for the safety of those they are supposed to be ministering to, decide to part company and go their separate ways, thinking it would be best if they move through the country alone, hopeful that by doing so they’ll touch more lives as well as find Father Ferreira faster.

Martin Scorsese has wanted to adapt Shûsaku Endô’s 1966 novel Silence for almost three decades. A labor of love, the film certainly fits perfectly alongside both of the director’s previous religious epics, 1988’s The Last Temptation of Christ and 1997’s Kundun, this nuanced, meticulously realized saga of two 17th century Portuguese missionaries lost in a strange land as uncomfortably unforgettable as it is cryptically compelling. This isn’t a movie for the faint of heart, the struggles of not just this pair of devout men but also those who follow them a complicated sojourn of faith, suffering, forgiveness, sacrifice and grace that left me bruised, battered and stunned by the time it ended.

But how to make sense of it all? As far as that question is concerned, honestly I don’t have an answer. There is a war raging within Scorsese and fellow writer Jay Cocks’ (Gangs of New York) complex, character-driven screenplay, the battle for Rodrigues’ soul as hard fought and as devastatingly brutal as anything that can be imagined. What it is all about, the themes they are playing with, none of it is clear which apparently is exactly as the duo wants it all to be, the religious discussions roiling through the proceedings a razor sharp samurai sword of violence and compassion that’s as likely to be placed within its sheath as it is to slice an unsuspecting believer’s head clean from their neck.

It’s difficult to watch, and not just because of the bloodletting and the violence. No, as extreme as all that is, the carnage also fits in with the nature of the story with haunting ease, and as such the savage nature of what is depicted is never as repugnant as it likely would have been in a lesser filmmaker’s hands. It’s the formality of the piece that makes it so prickly, Scorsese presenting a world of such rigid structure and social hierarchies the quiet menace sinks in all the deeper because of it. The filmmaker is channeling Japanese masters like Yasujirô Ozu or Masaki Kobayashi, the construction and tone just as important as the underlying emotional nuances that push each character forward along their respective paths.

It also reminded me a great deal of Scorsese and Cocks’ first pairing, the superb The Age of Innocence, that cold, bleakly austere 1993 rendering of Edith Wharton’s classic novel every bit as measured as this new opus. Much like that masterpiece, the director refuses to play be the rules, flouting genre conventions whenever and wherever he can. Silence rushes slowly towards its astonishing conclusion, the fires of conscience and sacrifice revealing new, perplexing truths that put all that had come before into brand new perspective.

Garfield, so spectacular just a couple of months ago as the brave heroic pacifist Desmond Doss in Mel Gibson’s Hacksaw Ridge, is excellent, giving as much of himself as he can in order to make sure Father Rodrigues’ inner tumult and struggles register. Driver is also superb, virtually unrecognizable as Father Garupe, his face oftentimes contorted in a marsupial-like manner that slowly led me to believe his journey was one of intelligent everyman into a selfless sacrificial beast than it was virtually anything else.

It is the Japanese actors, however, who make the most indelible imprints. Tsukamoto, a renowned director in his own right, known for classics like Tetsuo, the Iron Man and Nightmare Detective, is agonizingly marvelous, his final moments aching with a full-bodied tenor that brought tears to my eyes. Equally amazing is Oida, his tender embrace of the two Father’s after they first come to his village magnificent. As for Kubozuka, in many ways his Kichijiro is the Judas Iscariot of the piece, and watching this wretch return time and time again pleading for forgiveness for mistakes made and wrongs wrought shattered my heart into a million little pieces when all was said and done.

But all of them pale when stood alongside Ogata’s genius as the inquisitor Inoue. Playful. Murderous. Conniving. Understanding. Ruthless. Forgiving. He weaves all of the man’s varying shades into a colorful cloth of mirth and menace that is unnervingly fascinating. Ogata is the grey all the story’s blacks and whites meld into by the time the winds of change swirl into their quiet hurricane, the actor orchestrating the mournful symphony playing in the background with cagey resolve. He’s smarter than everyone else, manipulating others to do his bidding with easygoing precision, his reasons for attempting to stomp out Christianity before it can plant its seeds not nearly as simple or as obvious as might initially be believed.

The film itself is constructed with Scorsese’s typical attention to detail, cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto (The Wolf of Wall Street), production designer Dante Ferretti (Hugo, The Aviator) and legendary editor Thelma Schoonmaker (The Departed, Raging Bull) all rising to the occasion. It should also be noted that the film’s sound design is flat-out incredible, the immersive structure of the sonic landscape the director has had composed giving things a devastatingly eerie quality that kept me off-balance for all of the film’s 161 minutes.

Even so, it’s impossible for me to explain exactly how I felt walking out of the theatre once Scorsese’s latest came to an end. I think his adaptation of Endô’s book has more to do with grace than it does suffering, that it asks the viewer to forgive the trespasses of others more than it wants them to revel in the pain being inflicted upon even the most devoted and pious of the true believers. But I honestly cannot say for certain, and as such, Silence is a troubling, emotion-fueled enigma, and only through additional viewings do I believe an understanding of what it is Scorsese is attempting to say will ever be determined.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)