“The Journey” – Interview with Nick Hamm

by Sara Michelle Fetters - July 10th, 2017 - Film Festivals Interviews

a SIFF 2017 interview

Celebrating Compromise

Nick Hamm on Making The Journey a Trip Worth Taking

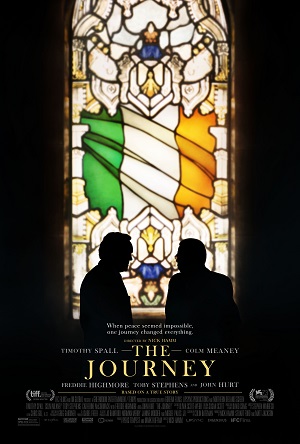

Nick Hamm’s The Journey is an intriguing flight of fancy. Inspired by a story involving Protestant religious leader Ian Paisley, a staunch British loyalist, and Sinn Féin representative Martin McGuinness, a high-ranking commander in the Irish Republican Army, the Killing Bono filmmaker was inspired to do something a bit unusual. As the story goes, during the 2006 peace talks in Scotland, the two men, who had never spoken a word to one another publicly, found themselves on the same flight back to Ireland. What was said, what they talked about, all if it was, still is, a closely guarded secret. But it planted a seed that blossomed into a full-blown peace accord, the two men respectively becoming First Minister and deputy First Minister of Ireland in May of 2007.

Hamm, inspired by this story, couldn’t help but wonder what it might have been the two men spent their time talking about during this trip. “I thought that the relationship between these guys was so incredibly interesting,” the director mused. “I thought that, basically, this was one of the most interesting contemporary political relationships that I had ever come across. Here were two people who were severely opposed to each other on every level, and kind of hated each other with every fiber of their being, and yet managed to peel beyond that constituency and that base to other people and create a situation in Northern Ireland where they opened the door to peace.”

Having watched The Journey during this summer’s Seattle International Film Festival, I had the opportunity to briefly touch base with the filmmaker via phone a couple weeks after its local screening. We spoke at length about numerous aspects of the film’s creation, most notably on the essential themes Hamm wanted to emphasize. “The fact is that this relationship changed history and it made history,” he states. “It facilitated people to stop killing each other. That was the truth. That’s the truth of it. What I did is I fictionalized this one part of a relationship that took years to come about. I think I fictionalized the essence of it, this relationship, because in the end I thought it was such an extraordinary testament to peace.”

Working with screenwriter Colin Bateman, Hamm moved the location of this meeting between Paisley and McGuinness to a car transporting the two to the airport being driven by a supposedly clueless chauffeur (portrayed by Freddie Highmore) clandestinely working for highly esteemed British negotiator Harry Patterson (John Hurt). Revered character actors Timothy Spall and Colm Meaney portray Paisley and McGuinness, the two seasoned veterans having a grand time verbally sparring back and forth as they bring these men to life.

Even so, by necessity the filmmakers had to blur the line between fact and fiction. “I tell you what,” explains Hamm. “The actual plane ride was real. There were more people on the plane than just [them]. It was actually a private jet. They were flying them back to [Northern Ireland] for Paisley’s 50th wedding anniversary and there were two or three other people on that plane, a couple of government ministers. I saw video footage, because somebody had actually recorded 15 seconds of those two guys talking with each other because they realized it was actually a historic moment.

“What they both said in that situation? There is no such thing as political absolute truth. That somehow gave us the license to dramatize what we thought would be a great story. In the end, it’s kind of a feel-good buddy movie. It’s like The Odd Couple in the back of a car.”

For this what-if scenario to work, it would take a pair of terrific actors to pull it off. Hamm found them in Spall and Meaney, and he never for a second failed to appreciate just how lucky he was to get them to play the parts of Paisley and McGuinness. “It’s really brilliant to watch amazing actors at the top of their game do something as powerful,” says the appreciative director. “I’ve watched it now in many different countries, with so many different audiences, and everybody responds to the power of those performances and what they ultimately deliver, which is an incredible amount of humor and a lot of emotion.”

Much of that humor and emotion is born from Bateman’s intelligently layered script. Even though the idea for The Journey was his, Hamm knew it was vital that he let his screenwriter come up with the ins and outs of the actual story for himself. “Yeah, that is true,” responds the filmmaker. “I came up with the idea, but then as a director you can’t really legislate [the script]. It’s all about execution. It’s all about whether a writer can pull it off. If they can’t pull it off then it doesn’t matter how good the idea is, it just won’t work.

“What Colin did is, I think, is compose something both intimate and public. He sort of managed to put two very public people in a private setting, and make them very, very human and very, very identifiable. As two politicians who reached beyond their base and reached beyond their own constituency, securing something that was pretty remarkable.”

But in telling that story, it was key that both the writer and director were on the same page thematically. It would have been very easy for the script to turn preachy, to beat the viewer over the head didactically with the themes and ideas Hamm and Bateman were hoping to address. This was a trap the director was determined to avoid. “That’s actually the entire job of what we did in the editing room and the shooting of [the film],” says Hamm. “Each guy is kind of like a boxer in a boxing match, and they go round to round with each other. You watch a scene, you think McGuinness won this one or Paisley won that one. What you need to is to be able to cut away from the boxing match, so that the audience can breathe a little bit, and understand the context a little more and maybe follow a little bit of the peace story and see some of the great countryside, not just arbitrarily but in a cinematic way. You keep the movie going but when you cut back to them the audience wants to cut back to [Paisley and McGuinness]. They want to see them. They want to be part of those scenes.

“That’s the trick of it. If every time you cut back to the guys the audience is going, ‘Oh God, not again,’ you’d be in real trouble. But because the reverse is true, they want to see what [Paisley and McGuinness] are doing. Also, there’s the time limit. We all know they’re going to the airport. So you know you’re not in the care forever. So you know you’re gonna throw all these different curveballs in there whereby the car gets a puncture and they end up walking through that churchyard. There’s a lot of stuff that happens to them to make the car journey longer. But you still have to get to the airport. You have got to be plausible with that, because otherwise the audience won’t accept the fictional reality of what’s going on.”

Even with a few excursions outside, the bulk of the film does take place inside an automobile, the difficulties of shooting these conversations between the two men in a manner that would be consistently compelling not lost on the filmmaker. “I’m really, really, really good at shooting dialogue in cars,” he says with a laugh. “We sort of had a mobile studio. We took over a massive stretch of freeway and put the cameras in there with the actors. It was about rolling with the changes all the time, using the right shots and finding the best performance.”

As terrific as Spall and Meaney are inside the car, it are the moments when they step outside that hit home with the most emotional forcefulness, a key sequence in a church graveyard in particular. McGuinness recollects on his life, the orders he’s given to his men and the violence those decisions have sometimes led to. It’s a heartfelt moment of honest recollection, but one that very easily could have lapsed into melodramatic treacle had Hamm and Bateman followed typical narrative convention.

“I’m so glad you point this scene out,” the director states proudly. “I think it’s probably my favorite scene in the movie. We all think [Paisley] is gonna wrap his arms around McGuinness and tell him not to worry, that it will all be fine. That he agrees with his adversary. That this was a terrible thing. But Paisley doesn’t do that. It’s his last attack on McGuinness, isn’t it? He realizes that he’s maybe gone a little too far but it’s still a very clever scene because it’s the right scene. That’s completely what would happen. I think it’s a great surprise, that scene. And Spall just nails it.”

That’s not the only moment Spall is extraordinary, the veteran character actor having an even more explosive moment at a gas station after their driver’s credit card is turned down by a clues attendant who has no idea who it is he’s refueling. “He kind of did become Paisley in that moment,” says Hamm. “It’s funny, trying to shoot that scene, because we were in the middle of the night at this small little gas station in the middle of nowhere and it was howling with rain. He couldn’t get it, he couldn’t get the speech. He felt it was way tricky and we kept pausing filming and finally I told him to just go take ten minutes. Tim went off, sat down and listened to some of Paisley’s speeches. He just walked back in and sort of did it. He had found the tone for it. Even people in Northern Ireland, they kind of rock with laughter when this scene happens.”

As we chat about the actors, the conversation cannot help but turn towards the late, great John Hurt, his appearance here as Harry Patterson one of his last. “He was ill,” says Hamm matter-of-factly. “We knew he was very sick when he was shooting the movie. But John wanted to make the film; he wanted to say those words. I think he wanted to work up until the very last moment. There was a massive sense of denial with John, that he was actually as sick as he was. But everyone knew it, and he knew it, too. He couldn’t sustain many hours on set. He could only do a bit, and then we’d have to send him away so he could rest and then he’d come back again. But I’m so glad he is in the film, that he played this part. His voice and his presence, I don’t know, it makes the movie eternal in some way.”

In the end, the story at the heart of The Journey is one Hamm feels audiences will respond to, this tale of reconciliation and forgiveness in the face of decades of mistrust and hatred one he feels has special resonance during this current tumultuous political climate. “The film is timely,” he states unequivocally, “and it is becoming more timely. The movie is a celebration of conciliation. It’s funny and it’s humane and it makes you have a very big emotional response to it. But, ultimately, it is a celebration of concession and a celebration of compromise.

“In a world where we practice intransigence at a kind of heavy level, it seems to me we’re in a period of time where politicians don’t speak beyond their base, that they only speak to their constituents. The movie shows two very brave people who choose not to do that, taking their constituents with them on a perilous journey towards compromise. It seems to me that’s what we’re ultimately celebrating with the picture; compromise and the ability to live together.”