Character-Driven Wildlife an Emotionally Raw Heartbreaker

Golf pro Jerry Brinson (Jake Gyllenhaal) has moved his family to a small Montana town to take a job at a local country club. Not only does this mean a new school for 14-year-old son Joe (Ed Oxenbould), it also forced his wife Jeanette (Carey Mulligan) to give up her position as a substitute teacher and become a full-time housewife. But when he shockingly loses his job after a bizarre misunderstanding with his boss, mother and son are forced to pick up the financial slack. Joe gets an after-school job working as a photographer’s assistant while Jeanette puts her teaching skills to good use getting a part-time position as a swimming instructor. All the while Jerry quietly stews, their dual success making him feel emasculated as they’re both out there picking up paychecks while he drowns his sorrows in a bottle of beer.

Even though the pay is terrible and the work is dangerous, Jerry joins a local crew to help battle wildfires up near the Canadian border. Jeanette is livid, thinking her husband is being an egotistical fool, that his anger that his wife is making more money than he is has caused him to take a job that could easily result in his death. In fact, she’s so angry she begins to rethink why it was she allowed Jerry to move them to the middle of the desolate nowhere in the first place. Looking to rediscover her fading youth, and in her own attempt to battle her growing sense of loneliness, Jeanette begins a flirtatious friendship with wealthy businessman and war hero Warren Miller (Bill Camp). More, she allows Joe to see all of what is going on between the two of them, believing he has every right to know his parents aren’t perfect and that they have personal lives outside of their raising of him.

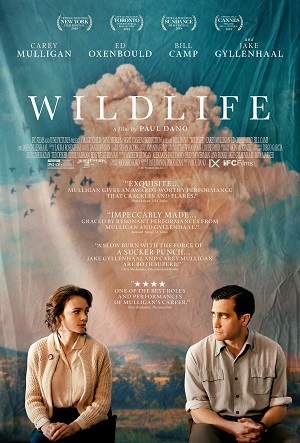

Everything and nothing is happening inside actor Paul Dano’s directorial debut Wildlife, a superb adaptation of Richard Ford’s 1990 novel. Featuring a delicate, effortlessly balanced script he co-wrote with Zoe Kazan (Ruby Sparks), Dano’s film has an observational spark of insightful intimacy reminiscent of Kelly Reichardt’s Certain Women or Chloé Zhao’s The Rider. It is a movie uniquely in tune with its early 1960s environment and one that grows in emotional urgency as it goes along. Featuring a spellbinding central performance from Mulligan and strong supporting turns from Gyllenhaal, Camp and Oxenbould, I kind of loved Dano’s film, the fact that is has continued to haunt, vex and intellectually stimulate me over a month after my first viewing a big reason why.

A big reason for this is the fearless complexity of Jeanette’s character. We do not typically see women like her in modern cinema outside of femme fatales, prostitutes or villains, especially not stories set in the 1940s, ‘50s or ‘60s. But Dano and Kazan allow Jeanette to be her own person, flaws and all. She loves her son. She maybe loves her husband. She wants to make their life in Montana work. But she also wants to be her own woman. She wants to feel valued. She doesn’t want to be left at home wondering where the most productive years of her life disappeared to. This is a woman who makes painfully bad decisions but also tries to be as honest about them as she believes she can be. Jeanette is a walking, talking conundrum, her contradictions and shortcomings making her human and as such far more believably authentic than she otherwise would have been.

This unsurprisingly gives the talented Mulligan fertile emotional earth to plant seeds within, her performance blossoming into something gorgeously spectacular. The An Education Oscar-nominee is spectacular, and oftentimes it is what goes unsaid, the numberous quiet moments, where she proves to be the most heartbreakingly authentic. The jittery physicality of Mulligan’s portrayal is frequently surprising. She shares scenes with Oxenbould that are mesmeric in their uncomfortable specificity, Jeanette’s attempts to explain to Joes what is going on with her, his father and her relationship with Warren creating more self-inflicted emotional wounds than they heal.

There are some third act speed bumps. A fiery scene between Gyllenhaal and Camp doesn’t work, Jerry’s actions not ringing with the same sort of character-driven realism that almost everything else in the movie seems to showcase. Also, as good as Oxenbould is, and even though Joe is the observer whose eyes the audience views all of this marital self-destructive carnage through, I can’t say Dano and Kazan’s script treats him with the same sort of multidimensional nuance as it does either Jeanette or Jerry.

Yet this remains a movie I can’t get out of my head. Dano’s debut effort has latched onto me in ways that defy easy description. It pokes and prods, the film breathlessly unafraid to break its characters down to their most basic elements, stripping them naked so that their flaws are as clearly on display as their strengths are. Wildlife is a quiet, introspective marvel that only grows in lasting resonance the further away I get from it, the lasting imprint it has made upon my psyche one I’m going to treasure for some time to come.

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)