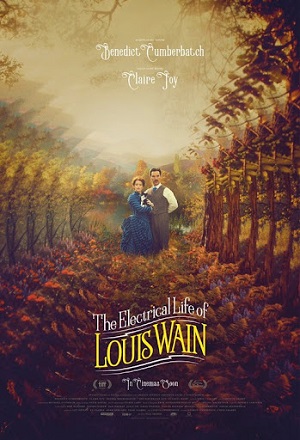

The Electrical Life of Louis Wain (2021)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - November 11th, 2021 - Movie Reviews

Whimsically Eccentric Louis Wain a Biographical Conundrum

The Electrical Life of Louis Wain is a suitably strange biopic that goes out of its way to emulate the documented idiosyncratic peculiarities of its subject. It’s also a movie I wish I enjoyed far more than I frustratingly did. This tragic tale of artistic genius, personal heartbreak and psychological imbalance never came together in my opinion, and as such this ended up being a docudrama I admired for its ambition and borderline despised for its lack of emotional authenticity.

I do give credit to director and co-writer Will Sharpe for trying to do something different. He’s not interested in checking any of the normal biographical boxes. Instead, he tries to directly channel the spirit of his protagonist, vaunted Victorian artist – known around the world for his surrealistic cat paintings – Louis Wain. His illustrations of big-eyed felines are instantly recognizable to this day, and it is no surprise that the man responsible for these unconventional artistic triumphs lived a life well outside the norm – at least by the standards of polite British society circa the late 19th century.

For actor Benedict Cumberbatch, Louis Wain fits right inside The Imitation Game Oscar-nominee’s go-to wheelhouse of stiff-upper-lip eccentrics. The artist is a jittery meld of Alan Turing, Dr. Stephen Strange, Sherlock Holmes, Thomas Edison and Julian Assange all rolled into one. He’s all quiet asides and sudden hyperkinetic outbursts, Louis keeping his emotions close to the vest only to reveal the core of who he is and what he is feeling at the most unpredictable of moments.

While Cumberbatch is terrific, I can’t say he blew me away, either. As much as Sharpe and co-writer Simon Stephenson try to shake things up with their screenplay, the overtly weird and nonsensical aspects of their scenario still play right into the confidently self-assured hands of their lead actor. Cumberbatch slips into Louis’s skin as if it were an old leather shoe he’s owned for years and has stretched to fit his foot perfectly.

While this sounds great – and it certainly isn’t a bad thing – it unfortunately allowed me to feel like, for as much as Sharpe was going out of his way to make me believe otherwise, I’d seen so much of this before. Unlike Louis’s paintings, there is no life to the images the director tosses up on the screen. It is as if he is getting weird more because he can then for any other reason. I never felt like I was learning more about the artist, the core of who he was and what made him tick kept a whimsical enigma for most of the almost two-hour running time.

It does not help that the women populating this tale, all of whom played a vital role in Louis’s story, are given an obnoxiously irritating short shrift. Andrea Riseborough does what she can as Caroline, the eldest of the artist’s four sisters, but she’s never around long enough to make the sort of lasting impression I can’t help think was the intent. Where her brother was notoriously terrible with money, and as women were not allowed to earn a livelihood of their own, Caroline is the one who early on does her best to keep Louis focused.

But as important as this relationship is, Cumberbatch and Riseborough rarely get the opportunity to connect. Louis and Caroline don’t coexist, and as such the complications arising later in the future come across as ham-fisted and infuriatingly melodramatic. Worse, it makes a future tragedy involving the duo have almost no impact whatsoever, and where I arguably should have been wiping away tears, instead I was shaking off a nonplussed shrug as I waited to see where events were going to take Louis next.

Fairing a bit better is Claire Foy. She portrays the young nanny, Emily, whom Caroline convinces Louis to hire to look after their younger sisters. Pretty soon he’s falling madly in love with the woman. The pair ultimately marry, and the resulting scandal forces the two to move into a quaint country cottage that’s as close to being isolated from British society as they can get.

Foy is luminous, and she does have a bit more to play with and portray than Riseborough. The scene where she and Cumberbatch come into possession of the kitten that will change Louis’ life forever is utterly charming. This moment happens not so long after their characters are given devasting news regarding Emily’s health, and so this spark of unexpected joy as they decide to take the critter into their home is as warm and as genuine as a ray of sunshine piercing through the clouds on a gloomily overcast day.

Yet Foy isn’t given enough to do for Emily to truly three-dimensionally register. She’s an ethereal enigma, a haunting presence who will continue to captivate and motivate Louis long after she is gone. But this makes her more of a narrative device than it does an actual human being. The way the character is structured left me wishing Sharpe and Stephenson has spent a bit more time fleshing her out and not left so many blanks for the viewer to fill in seemingly all on their own.

But I do love how Sharpe takes such a psychedelic approach to Louis’ biography. Considering all the artist endured throughout his life, that the filmmaker balances so much unimaginable tragedy with a flurry of rhapsodic whimsy is moderately astonishing. There is something wonderful in watching this artist embrace his cat creations and, even as his mental faculties deteriorate, that Louis remains true to his convictions as he battles all sorts of hardship can’t help but be mildly thrilling.

So I’m torn. It’s as if Sharpe has painted only half of a picture and left the remainder a mysterious enigma never to be completed. But there’s enough magic in The Electrical Life of Louis Wain to warrant a look, just not near the volume required to warrant a full-blown recommendation. I’m annoyed and inspired in almost equal measure, and whether that’s a positive or a negative I honestly have no idea.

Film Rating: 2½ (out of 4)