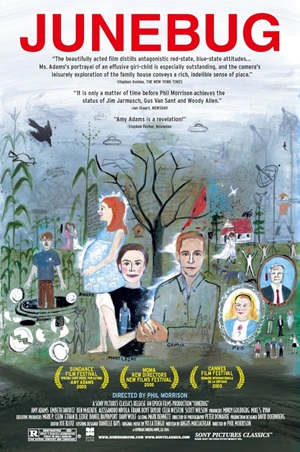

a SIFF 2005 review

Hollerin’ for Amy Adams and Junebug

Art dealer Madeleine (Embeth Davidtz) goes into the North Carolina countryside to woo a renowned local painter for her upscale Chicago gallery. She and her husband George (Alessandro Nivola) decide to extend their trip to include a visit to his nearby family home. Once they arrive, his father Eugene (Scott Wilson) is introspectively quiet, his mother Peg (Celia Weston) distrustful of the new wife, and his younger brother Johnny (Benjamin McKenzie) a brooding, chain-smoking mess.

Only Ashley (Amy Adams), Johnny’s talkative and perkily pregnant wife, embraces Madeleine, immediately latching onto her as the big sister and role model she’s always wished she had. She adores her new sister-in-law, and the innocent mom-to-be isn’t timid about making sure everyone knows it.

Music video director Phil Morrison’s debut feature Junebug is the type of movie you want to see twice in quick succession. It’s obvious from the get-go that the performances, especially the stellar work from Adams, are exceptional. But the movie does leave a strange aftertaste. No one really changes all that much by the time the credits roll. It’s all about little kindnesses, about small observations, and it is in those quiet empathetic moments that Morrison’s drama soars.

This is a picture centered on people from different worlds looking to get along. Each family member learns to accept the other for who they are, but they do so by staying true to their core values, most of which are never forced and are always played close to the vest. The whole drama is built on a foundation of varying shades of grey. It revels in the subtle differences between mother and daughter, father and son, and brother and sister, all of which make life so inherently head-scratching and magnetically bewildering.

But the film is also a celebratory party for Adams. She’s magnificent, the actress delivering a rapid-fire performance so electrically invigorating it gave me goosebumps. Ashley is a blabbering dynamo of feminine disassociation, reaching so hard for a brass ring colored with acceptance and female companionship that she barely notices that her own husband is quietly falling apart. It is such a beautiful portrait of resilience and aspirational heartbreak, and I can’t begin to fathom what any of this would have been like without Adams’s presence.

The majority of the ensemble also shines. Davidtz gets her meatiest role since Schindler’s List, while veteran character actors Wilson and Weston get full-bodied parts equal to their respective talents. O.C. hottie McKenzie is also quite good, but it wasn’t until the picture’s second half that I began to realize how nuanced his portrayal of the forlorn Johnny truly was. Only the usually reliable Nivola disappoints, his turn as the emotionally closeted George unfortunately not doing a lot for me.

Morrison directs with confidence. Both he and screenwriter Angus MacLachlan aren’t afraid to take chances from a narrative standpoint. But that doesn’t mean the filmmaker does anything technically astonishing. Just from a visual perspective, things can become rather static, with cinematographer Peter Donahue and editor Joe Klotz doing solid if unspectacular work. Showy this picture is not.

The thing is, this is a meat and potatoes story, so this somewhat bland visual aesthetic fits rather nicely. This is a movie about real people with genuine issues and it handles them all with insightful decisiveness. I was genuinely moved.

Junebug opens with some southern locals practicing an art form known as “hollerin’.” This musical cry was once a practical form of communicating in North Carolina, and seeing and hearing it performed here is queerly mesmerizing. But I feel that way about Morrison’s debut as a whole (and Adams’s performance in particular), and if ever there was an intimately affecting indie worth hollerin’ about, it’s this one.

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)