Millers in Marriage is a Depressive Midlife Crisis Triptych of Marital Disintegration

There’s something about the films of writer-director Edward Burns that’s always kept me at arm’s length. I admired more than loved his hit, ultra-low-budget 1995 debut The Brothers McMullen, and I cannot say my appreciation for his storytelling abilities has substantially grown over the succeeding 30 years. The one exception was his sophomore outing, 1996’s She’s the One, which I did enjoy. But other than that? It’s all been a downward spiral, and not even Burns’s charms as an actor — of which there are plenty — haven’t done much to overcome my overall aversion to his directorial filmography.

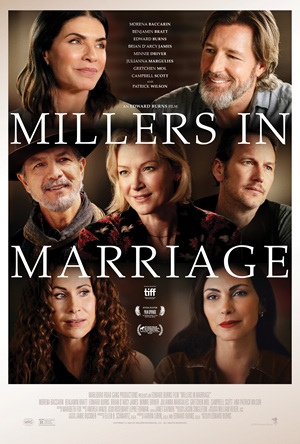

This does not change with his latest adult melodrama Millers in Marriage. While Burns has assembled a stellar ensemble — Minnie Driver, Julianna Margulies, Patrick Wilson, Morena Baccarin, Benjamin Bratt, Gretchen Mol, Brian d’Arcy James, and Campbell Scott — the story he’s telling is a mostly unpleasant slog. The whole thing is a well-acted descent into the depressively mundane, and 117 minutes of one banal struggle after another was not my cup of tea.

This is the tale of three different marriages in various stages of crisis (one of which has already failed, more or less), all of it revolving around the siblings Miller: Eve (Mol), Maggie (Margulies), and Andy (Burns). Eve is searching for her alcoholic husband Scott (Wilson) who has gone missing after his latest business trip. Maggie and her husband Nick (Scott), both writers, are dealing with unexpected complications after their youngest child has flown the coop. As for Nick, he’s in a fresh relationship with the vivacious Renee (Driver), even though he’s still harboring not-so-secret feelings for his ex-wife Tina (Baccarin).

I’m okay with dramas that drown themselves in misery. When the writing is sharp, the performances are solid, and the emotions are authentic, there are plenty of character-driven wonders that can be explored; just ask William Shakespeare, Tennessee Williams, Norman Mailer, Dorothy Parker, and Noah Baumbach. Familial pain can be cathartic for a viewer, even when the end result isn’t particularly uplifting.

In this instance, however, everything hit me as being aggressively downbeat only for the sake of being aggressively downbeat. Practically none of these characters are likable and, the ones that are, have precious little to do and receive outcomes (both closed and annoyingly open-ended) that are risible in their obtuse hopelessness. Even moments of joy come across as only another outlet for misery, and not even Driver’s effortlessly euphoric smile can make even a tiny crack in this film’s oppressively glum foundation.

However, she does give it her best shot. Driver comes tantalizingly close to making something meaningful out of Burns’s avalanche of dreary nonsense. She may have an underwritten character, but the actor still nonetheless remains a mesmerically singular talent. There are moments between Renee and Andy that have surprisingly potent emotional elasticity. Additionally, not only does Burns and cinematographer William Rexer (Summer Days, Summer Nights) give Driver the full movie star treatment as far as framing and lighting are concerned, but the director also has the good sense to play second fiddle to her overall luminescence every time they share the screen.

Other members of the ensemble shine as well. Benjamin Bratt pops up as a music critic, and while the less said about his inclusion in the drama the better (as saying more could be construed as a spoiler), every second he appears is like an unforeseen gift dropped in from a completely different — and far better — motion picture. Margulies is also excellent, and as events progressed Maggie ended up being the only member of the Miller siblings I found myself caring to know more about.

Best of all is Scott. Maggie and Nick have entirely opposite reactions as far as their writing goes once their youngest child heads out the door. She has never felt more creatively unencumbered. He, on the other hand, is suffering from the worst writer’s block of his career. Scott makes even the most cliché idea come off as heartbreakingly genuine. He has moments of wrenching insight that ripped me in two. In fact, at a certain point, I admit I started to wonder what might have been had Burns narrowed his focus and composed a script revolving around these two characters and no one else. Their moments together have that much potential.

That’s not what Millers in Marriage is, though. Instead, Burns delivers a midlife crisis triptych of familial strife in a post-COVID (yet decidedly pre-Trump 2.0) America that never coalesces into anything meaningful and features even less that’s worthwhile. The world is in chaos. Making any relationship, let alone a marriage, last in this environment is unquestionably difficult. I respect that Burns wants to analyze all of that in an adult manner. I only wish he’d have added fresh insight or crafted something emotionally engaging in the process.

Film Rating: 2 (out of 4)