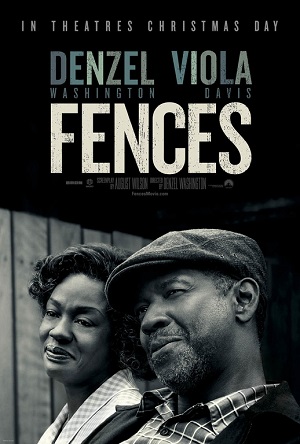

Washington’s Fences Adaptation an Absolute Triumph

In 2010, Denzel Washington and Viola Davis headlined a Broadway revival of August Wilson’s 1985 Pulitzer and Tony Award-winning play Fences. It garnered rave reviews, giant box office receipts and Tony Awards for Best Revival, Best Actor and Best Actress. Even so, the transition from making the leap from stage to screen was not instantaneous, and even with Washington’s box office clout as no Wilson play had ever been adapted for cinema garnering Hollywood studio interest was not an overnight affair.

It was worth the wait. Washington, reteaming once again with Davis, choosing to direct the project himself making it his third outing behind the camera and first since 2007’s The Great Debaters, working from a script fashioned by Wilson himself before his death in 2005, Fences is, in a word, triumphant. While not entirely able to escape its roots in the theatre, while feeling like a filmed version of the play on more than one occasion, nonetheless this is still a striking motion picture, one filled with life, drama and devastating emotion. As for Washington, he has done his best work as a director while also turning in one of the finest performance of his two-time Academy Award-winning career, delivering a feature certain to be talked about, discussed and cherished for many years to come.

Set in a small mid-1950s Pittsburgh neighborhood, the story revolves around sanitation worker Troy Maxson (Washington), a hard-working everyman who hasn’t quite been able to get over the fact that by the time Major League Baseball integrated he was then sadly too old to play. Even so, he comes home every night to his wife Rose (Davis), sharing a bottle of gin each and every Friday evening with his best friend and coworker Jim Bono (Stephen McKinley Henderson). His eldest son (from another mother), musician Lyons (Russell Hornsby), always seems to mosey around the house on around that time as well, knowing it’s his father’s payday so he sneakily shows his smiling face hoping to get a five or ten dollar loan to help get through the week.

Troy is compelled to ride his youngest son Cory (Jovan Adepo), the boy he had while married to Rose, as hard as he can. The teenager is on the verge of graduating High School and is a promising football player, colleges eager to meet with his parents to discuss having him play for their respective teams. But Troy doesn’t believe Troy will be given a fair shake, doesn’t think he’ll get a decent opportunity to showcase his skills, and as such he’s insistent his son keep his job at the A&P and learn a good trade that will pay the bills as he gets older and school is behind him.

Wilson’s play has a lot on its mind, traveling through years in the blink of an eye as it examines these characters in intimately exacting detail, their life and times feeling as real and potent now as they ever did when the play first debuted back in 1985. Troy isn’t a good man, but he’s also not a bad one. He’s a human being, prone to monstrous acts but who is also just as apt to show a form of tenderness that’s as immense as it is selfless. This is a man who sees a world colored by the racism and hate he’s been forced to deal with since the second he was forced out of his own home as a youngster, wanting to see at least one of his children succeed where he believes he has failed.

As stated, Washington is extraordinary, his uncompromisingly freewheeling ferocity as Troy up there with the actor’s best work showcased in films as diverse as Glory, Malcolm X, He Got Game and Courage Under Fire. He revels in Wilson’s language, relishing every syllable as he barks it out, the actor standing tall no matter how weak and abhorrent some of the decisions the character makes sometimes prove to be. Washington does not compromise, one second winning hearts while in the next pulling them from someone’s beating chest in order to devour their flesh with carnivorous relish as the person looks on in abstract horror. He’s amazing, and if the actor ends up winning a third Oscar for his accomplishments it wouldn’t surprise me one little bit.

Even so, Washington is nothing compared to his costar. Davis, bidding her time, slyly underplaying her scenes early on in order to really dig in and turn up the heat as the plot twists, secrets come into the light and shocking human indiscretions are forced into the open, is incredible. She hypnotically captured my attention whether she was quietly knitting a sweater or spewing venom into the face of the man she’s sharing the screen with. This is such an exceptional character, the veteran actress playing up her varying nuances with stunning ease. Davis blew my mind, and as strong as she was in The Help and in Doubt I was still unprepared for her unparalleled brilliance as Rose.

The whole cast is beyond reproach. The ensemble Washington has assembled, which also includes Mykelti Williamson as Troy’s brain-damaged brother Gabriel, work together like clockwork, each actor clicking so perfectly with the other members it’s almost as if they’re out there living this life and not acting it out up on a movie screen. For my money, Henderson is the chief standout, the familiar character actor getting an opportunity to shine like he never has before.

I cannot say Washington opens things up as much as he potentially could have, and as in the play he keeps things pretty much centralized on Troy and Rose’s backyard, with only occasional forays into the couple’s living room and kitchen. Still, he allows cinematographer Charlotte Bruus Christensen’s (Far from the Madding Crowd) camera freedom to move, allowing for a sense of motion and movement that otherwise would not exist. The film is also exhilaratingly edited by Hughes Winborne (Crash), the Oscar-winner piecing things together as if to make me feel like I was a voyeur peering at the Maxsons from the others side of the alley, eavesdropping on personal conversations I maybe wasn’t supposed to overhear.

It all comes back to Wilson’s play, however, and Washington lets the author’s words do all the heavy lifting. The majesty of this play has always been its courageous honesty, and like Harold Pinter or Tennessee Williams at their best, the playwright’s willingness to look his characters’ demons right in the eye and not turn away is not something to scoff at or belittle. Fences runs on that energy, bobbing and weaving as it rolls through the years in order to deliver universal truths that shout volumes no matter one’s race, background or age. Washington has done Wilson proud, the veteran actor swatting this one right out of the ballpark, knocking the cover off of the ball in the process.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)