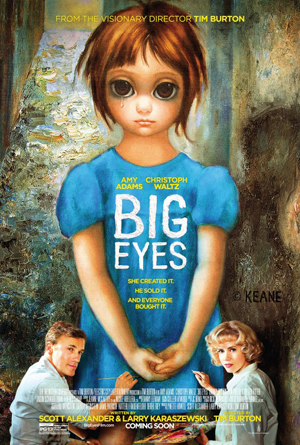

Burton’s Big Eyes Oddly Lifeless

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, Walter Keane (Christoph Waltz) looked like he had the world in the palm of his hands. A celebrated artist known for his depiction of big-eyed children in various stages of trepidation and despair, he helped revolution the industry making a mint selling copies and prints of his most treasured works making art consumable for the masses and not just the wealthy. He broke the rules and forged his own path, his paintings changing the art world forever in ways still being felt today.

Problem is, he didn’t actually paint any of the works he was most famous for, his wife Margaret (Amy Adams) did. He convinced her that no one would take the art seriously if her name was attached to it, if it were known that a woman was painting these surreal little children. She believed him, was certain he was right, and not until the two were long divorced and she’d retreated from California to Hawaii did Margaret find the strength to take her ex to court and state to the world she was the artist, him nothing more than a charlatan pretending to be one.

Reuniting with Ed Wood screenwriters Scott Alexander and Larry Karaszewski, Big Eyes is an obvious labor of love for director Tim Burton. More importantly, it’s a major step up from his last couple of live action efforts Alice in Wonderland and Dark Shadows, the film a suitably flamboyant look at a real life bit of craziness that no one ever would have believed had it not actually happened.

But does it rise to the same sort of heights Ed Wood gloriously did? Sadly, no. More than that, the idiosyncratic touches that made the film close to genius are oddly absent this time around, Burton, Alexander and Karaszewski taking a far more straightforward and by-the-numbers approach to the Keane story than anticipated. It’s strangely devoid of quirks and surreal little touches that would make it feel more than your average movie-of-the-week melodrama, and as such it’s nowhere near as interesting or as effective as it might have been otherwise.

Not that any of this matters as it concerns Adams. She’s terrific, make no mistake, delivering another exceptional, suitably authentic performance that feels truthful and real. There’s real insecurity and pain hiding in plain sight within this timid wallflower, a roaring tigress screaming to get out but incapable of making itself heard for fear of what doing so could mean as it concerns her young daughter (by another marriage) Jane. The joy she feels when completing a painting is palpable, as is her ultimate victory when Margaret sees her name restored to her work and Walter’s sent into ignominious shame. Adams is a delight start to finish, delivering a mesmerizing portrait of a woman finding the strength to come into her own that’s undeniably wondrous.

Waltz is also good, but in all honesty Walter Keane is so inside the two-time Academy Award-winner’s wheelhouse I can’t say he does anything that felt as electric or as lively as I hoped it would. The actor isn’t so much going through the motions as he’s delivering ticks and tricks we’ve seen from him a number of times before, and as such he never disappears into the role in ways that could have made the character even slightly memorable.

As for the rest of the all-star supporting cast, it’s a gigantic mixed bag as far as they all go. Jason Schwartzman and Jon Polito are sublime as respectively an art gallery clerk who belittles Walter’s work and a night club owner who finds unexpected profit in showcasing the big-eyed paintings on his venue’s walls, while Danny Huston is hard-boiled perfection as a San Francisco gossip columnist who unexpectedly becomes a big part of the Keane ruse. But Terrence Stamp is shockingly wasted as New York Times art critic John Canaday, while Krysten Ritter at first looks like she’s going to have a meaty part as Margaret’s best friend DeeAnn only to disappear and become oddly unessential just as things get interesting.

I applaud the fact Burton attempts to play against type and expectation. I like that he tones things down, attempts a more procedural-like approach to the material that eschews the surrealistic Charles Adams meets Rankin and Bass meets William Castle esthetic he’s typically so fond of. But stripped of much of his artifice, eschewing his usual cartoonish tendencies, he ends up making Big Eyes look and feel like a nondescript biography anyone without an even ounce of his talent probably could have directed and had it look and sound almost exactly the same.

That’s probably unkind, because it isn’t like Burton’s hand isn’t felt. Colleen Atwood’s (Memoirs of Geisha) costumes are perfect, as is Rick Heinrichs’ (Sleepy Hollow) superb production design, while composer Danny Elfman (Batman, Beetlejuice) once again delivers a score for the director that’s as essential as it is wonderful. Alexander and Karaszewski’s script has its fair share of bizarre little flourishes, like Margaret’s introduction to Jehovah’s Witness, Burton knowing just how to make these moments sing in ways that are undeniably memorable.

I just wish I felt more emotionally attached to all that was happening. Margaret’s story is an incredible one, and it’s hard to believe it hasn’t been told until now. More, Burton, his affinity and reverence for the artist and her work a matter of record, seems like the perfect choice to be the one to tell it. But Big Eyes, for all its moments of inspired whimsy, for as much as it admires and respects the painter, it’s still oddly lifeless as far as the bigger picture is concerned. The canvass isn’t so much empty as it is incomplete, a richer portrait required in order for the Keane tale to rise to the same priceless heights as the iconic paintings which inspired it.

Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 2.5 out of 4