Indescribable Henry Sure to Provoke a Wide Range of Emotional Reactions

The Book of Henry will not work for everyone. More, those that do not respond to the film are likely to hate it with every fiber of their being. Gregg Hurwitz’s script is a dangerous balancing act featuring a number of elements that make the skin crawl, including a central plot strand revolving around child sexual abuse involving a parental figure. That alone would make some potential viewers pause where it comes to buying a ticket. But director Colin Trevorrow (Jurassic World, Safety Not Guaranteed) is also attempting to emulate the tone of pictures like The Goonies, Radio Flyer and Stand By Me while also mixing in more elements that are as equally upsetting, making this one of the more unusual feel-good tales of self-discovery and familial empowerment to ever see the light of day.

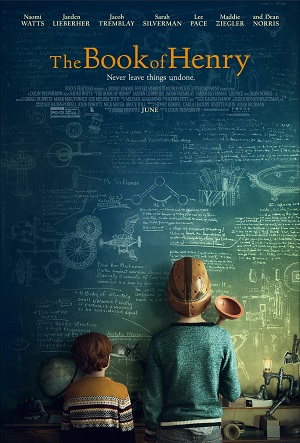

Henry Carpenter (Jaeden Lieberher) is 11-years-old. He is caring, empathetic and goes out of his way to stand up for others whenever he can. He is also a certifiable genius, a child prodigy who carefully engineers astonishing mechanical inventions while also planning his entire family’s financial futures. He’s more of an adult than his single mother Susan (Naomi Watts), little brother Peter (Jacob Tremblay) watching in wide-eyed rapture as Henry does one extraordinary thing after another.

Living next door to the Carpenters is Christina Sickleman (Maddie Ziegler) and her stepfather George (Dean Norris). He’s the trusted chief of police for their small suburban town, and Susan feels drawn to him in friendship while also paying special attention to his talented dancer daughter. But even she doesn’t notice what Henry does, the level of pain and suffering happening inside the Sickleman house when the lights go down when it appears no one is watching. Christina is in a bad place, and she needs help, but because of George’s position no one is going to believe an 11-year-old no matter how high his I.Q., so if something is going to be done to remedy the situation than he is the one who is going to have to do it.

So there’s a lot to unpack just from that short synopsis alone. But most of that is really only the setup. About halfway through the story things turn again, and instead of Henry being the star of the show it turns out this has been Susan’s saga all along. She is the one that must learn to control her grief. She is the one that must find a way to be a parent in the most unimaginable of situations. She’s the one that goes off the deep end, following the instructions of an exceedingly smart adolescent forgetting that, for all his intelligence, his life experience is barely a decade old. This single mother must find an inner strength she didn’t know was there, and in the process become the type of parent both of her children believed she could always be.

There are major parts of Hurwitz’s screenplay that make me sick to my stomach. The melodramatic elements that he assembles together are close to oppressive. More, they could be construed as offensive; especially in the manner in which complex, highly adult subject matter is utilized in a fashion more akin to a Steven Spielberg, Richard Donner or Chris Columbus ‘80s opus than a thought-provoking adult drama. If looked at straight on it’s all rather risible, there’s no denying that, and the cumulative volume of all of the punches to the gut and slaps to the face that Hurwitz’s scenario offers up incredibly difficult to get beyond. In other words, something like 2006’s Little Children this motion picture certainly is not.

Maybe I’m strange. Maybe I could tap into the mindset of the three main characters Henry, Peter and Susan in ways some will find bizarre. Maybe I’m just okay with melodramatic coincidences and contrivances while at the same time like to applaud a movie that takes major chances, isn’t worried about presenting difficult subject matter in a PG-13, mass audience way. But the truth is that I actually liked The Book of Henry. I was affected by what it was Trevorrow and Hurwitz were trying to do, aspects of the story that are beyond abhorrent working for me in a manner that I understand many will struggle to comprehend.

At least, it all worked for me during the first hour. Trevorrow does a fine job of juggling a number of distasteful plots and subplots, merging them together in a human and honest fashion even if the characters taking part in all this craziness were undeniably fanciful in an early Spielberg sort of way. He also gets two extraordinary performances from Lieberher and Tremblay, the duo showing that their strong work in efforts like St. Vincent, Midnight Special and Room was nothing close to a fluke. They have a naturalistic camaraderie that’s endearing, the intimate nature of their brotherly connection entirely sincere. A scene between them in a hospital room is flabbergasting, Tremblay particularly outstanding as he navigates a number of emotional complexities that caught me entirely off guard.

Watts is also marvelous, but she has an almost impossible task as far as her character’s evolutions are concerned. About the halfway point she becomes the focus of everything that is happening, and Hurwitz’s script doesn’t always know to keep these transitions from reeking of idiosyncratic convenience. Yet the actress anchors Susan with a conviction I found genuine, and as such I didn’t have that big a problem with her following the somewhat crazy ideas put forth by her 11-year-old son mainly because the ocean of grief they’re birthed from is palpably frank.

Look, I do not think the last third of the movie works. The pieces don’t fit together and the outcome, even in a modern dark fairy tale fantasy like this one, isn’t even slightly believable. It’s just too cute, too tidy, the tactics Susan and Henry initially utilize to help Christina out of her impossible situation ludicrously implausible. But it is more what transpires, the ugliness of it, not how it is all dealt with that will rub many the wrong way, that by planting these elements in a story such of this Trevorrow and Hurwitz have crossed some sort of moralistic line that’s beyond the pale.

I don’t buy that. I think Trevorrow actually handles this madness in a manner that is cathartically eye-opening, that feed the inner journeys the core group of characters all find themselves inexplicably on whether they realize it or not. There is something daring and crafty about this that forces the viewer to reassess how they look at themselves and the world at large, the darkness lurking underneath the surface sitting closer to home than most will find comfortable. The Book of Henry has issues, big ones, but subject matter I do not believe is one of them, the emotional richness flowing through these intergenerational familial revelations ones I continually responded to no matter how upsetting and uncomfortable the story itself might oftentimes be.

Film Rating: 2½ (out of 4)