“Boyhood” – Interview with Richard Linklater

by Sara Michelle Fetters - July 25th, 2014 - Film Festivals Interviews

a SIFF 2014 interview

Richard Linklater Explores Cinema’s Boundaries with Boyhood

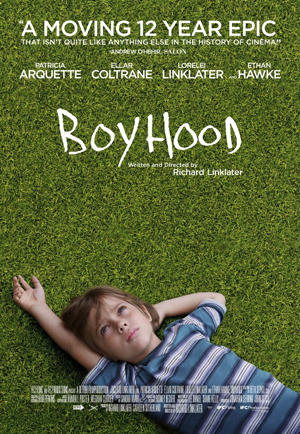

Shot over a 12 year period, Boyhood tells the story of Mason (Ellar Coltrane) as he ages from six to 18, looking at snapshots of his life at varying stages as he evolves into a young man ready to make the trek to college. Patricia Arquette stars as his divorced single mother, while Ethan Hawke appears sporadically as his happy-go-lucky dad, Lorelei Linklater rounding out the cast as older sister Samantha, also going from eight to 20 over the course of the film’s 165-minute running time right before our eyes.

It’s an audacious undertaking, and one that acclaimed writer/director Richard Linklater didn’t undertake without some small modicum of trepidation. “It’s just one of those crazy ideas that you have,” he says with a smile. “I was trying to make a film about childhood, but I couldn’t find a spot to begin. You’re limited. You’re seven, you’ve got to make a film about a seven-year-old. All my ideas were so spread out, though, and I didn’t want to be handicapped to being stuck at one place in time.”

“I’d kind of given up on the idea; then it hit me. One flash. My whole adult life has been about storytelling and narrative, cinema; I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about that. I think that’s what allowed me to have this idea, to push the boundaries of cinema in a certain way storytelling wise. Why couldn’t you just film a little bit every year? We’ll see the kids grow up and the parents age in one movie at the same time in the same tone. It’s a cool idea, but so impractical. But, you know, why not?”

All of which made for what was arguably the longest 39-days shoot in movie history – the director, his cast and his crew assembling once a year for 12 consecutive years fleshing out the trajectory and the dramatic arcs of the story as they went along. “We think we’re the longest scheduled production in history,” he states with a laugh. “We’re certainly the longest post-production. It’s pretty mind-boggling. But, like I said, it’s so impractical. I think that’s why no one has done it before us. It doesn’t make any sense.”

“In some ways it tells you how much of a business making movies is. The artists got it. Ethan was like, what a cool idea, he understood it immediately. He and the other artists I talked to about it engaged right away. But business people? They were speechless. They thought it was insane.”

It’s not surprising Hawke was onboard with the idea right from the jump. Considering his long relationship with the filmmaker, as well as the pair’s artistic triumph (working alongside Julie Delpy) with Before Sunrise, Before Sunset and Before Midnight, each sequel nine years removed from its predecessor, his leaping at the chance to be a part of this decade-long endeavor doesn’t come as a huge surprise.

“He embraced the idea immediately,” proclaims Linklater. “I remember the look on his face when I broached it with him. He was like, yeah, that’s such an incredible idea. Yeah. We should do it. He was part of the team even before I had a full idea let alone the initial makings of a script.”

But did Patricia Arquette know what she was getting herself involved with when she agreed to be a part of the film? Did she know just how much of herself she was going to need to add to the equation to make sure the picture would work? Just by the nature of the beast, her character is required to be a part of each year of Mason’s maturation, Mom the primary caregiver attempting to give her children the best life she can.

“Yeah, she knew,” says Linklater. “She’s fearless. Patricia tells me she remembers our initial conversation. She said I called her up and asked her what she was going to be doing 12 years from now. I said she would be looking for a part and I’d be trying to get a movie made, the same stuff we were already doing. Why not make sure we had something to work on each and every year while went about that part of the business? Sure enough, here we are.”

“But, 12 years, as an adult, once you reach a certain age you can conceptualize that. But as a six or seven-year-old? You can’t fathom what a decade is going to look like. That’s what I think made this idea so fascinating.”

That was also part of the problem. Finding adult actors willing to take on such a project was one thing, but finding children, let alone also finding parents, all of whom would be up for the challenge? That was a different thing altogether.

“My daughter insisted on being in it,” recollects the filmmaker. “[Lorelei] says she doesn’t remember it that way, but I tell you it’s absolutely true. She acts sometimes like I burdened her with this, but the truth is I would have been disowned by my own kid at eight had I not let her be a part of the film. Soon she realized what it was she’d signed up for and that she didn’t really want to act, but by that point it was too late. Lorelei jokes that she asked me to kill her character off, but that was never going to happen. She was a trooper, though. I’m proud of her and her performance.”

“For Mason, though, the film is so much from his point of view that I had to spend a lot of time casting the role. I met a lot of kids. It was important to me that they already be actors, they needed to have headshots and resumes because that would indicate to me they had family support. I needed to know they understood the undertaking; that I wasn’t going to whisk their child away from their normal life. I wanted it to be a positive thing. Something they could all track, look forward to every year. And that’s what I think it was. Heck, movie sets are fun for kids.”

Not that his star had any idea what it was he’d signed himself up for. “He couldn’t,” says Linklater plainly. “In the end, you were really signing up the parents because at six-years-old Ellar had no idea what it was we were asking of him. The parents were responsible for this big life decision.”

“For Lorelei, at least I knew where she would be every year, so letting her be a part of the film wasn’t that difficult a decision. For Ellar, anything could have happened. His family could have moved away. He could have decided he didn’t want to do this anymore. Anything could have happened, so I really had to trust the parents and put my faith in them that he would see things through until the end.”

“The irony is that Ellar ended up being the most solid. Patricia and Ethan, we were always having to juggle their schedules. Lorelei kept wavering about how much she wanted to do it every year – mainly just because I’m her dad. Had I been anyone else I don’t think she’d even ponder complaining, let alone [consider] trying to quit. But Ellar? He was a rock. He was there every year ready to go. He became a full-blown collaborator as he got older. We’d just hang out and chat and I’d find out what was going on in his life. Some of that got put into the script.”

That sort of collaboration was in many ways by design. Linklater knew that whatever narrative he came up with initially was going to be influenced by the maturation of his stars, there likes, dislikes, experiences and aspirations a vital part of the story he was wanting to tell.

“I got to spend the year between each period of filming gauging where they were,” he explains. “I always had to figure out what would work for the film developmentally, what would fit into the larger narrative structure. But that was a luxury. I had a year to ponder the next episode, to watch the edited footage we had compiled up to that point. I got to think about the relationships, think about what would be what. It was a collaboration with time.

“I always told Ellar the movie was going to pretty much go in whatever direction he goes to a degree. My preconceived ideas were always going to meet his reality, at some point they were going to meld together. I don’t think there was ever any question as far as that goes.”

The glorious thing about Boyhood is, in the end, just how simple it actually is. The director doesn’t throw in a lot of unnecessary baggage, doesn’t have anybody getting into a shootout, doesn’t have mustache-twirling villains popping up at inopportune times or unforeseen cancers ripping away loved ones with melodramatic ferocity. He just lets things happen as they would, using a documentary-like approach in order as he follows Mason along his 12 year journey. But what’s it all about in the end? That’s not a question Linklater likes to be asked.

“Anything but that question,” he laughs. “It’s life. Individually, some of the moments we live are pretty banal, but cumulatively there’s an effect, and experiencing them is how we know we’re alive. Moments take on meaning. Relationships grow. Things get infused with more emotion. You become more involved with the passage of time.”

“That’s what I wanted to happen here. I wanted people to get involved with this family and what it was that was going on with them. But I think that’s what makes the film something of a tough sell. They hear the idea and they think it’s probably going to be a great movie, but it also sounds like one they’ll rent instead of go out to see. They think that, if they’re going to pay money, if they’re going to park the car and get concessions and buy that ticket, they have to have some sort of mind-blowing experience. Hollywood has sort of taught everybody over the years that a lot of firepower and visual razzle-dazzle is what is important. That’s unfortunate.”

The director’s commentary on modern Hollywood is particularly noteworthy in some ways, as it isn’t just in concept where Boyhood eschews convention. For a coming-of-age drama about a boy growing into a man, the filmmaker isn’t interested in many of the big signature melodramatic moments most stories like this usually focus on.

“We’ve done that,” states Linklater emphatically. “We’ve seen that. That didn’t interest me. I had all this time to think about it. To look at what I wanted to showcase and explore. Do I show the first kiss? You know what, no, because for one thing I’ve seen it a million times, there’s nothing special cinematically about that. Also, no, because in my own life, that first kiss, it’s not what you think it is, it’s like I was an extra in a movie remembering it how I was supposed to remember it and not as it actually happened. But what about that third kiss? That fifth kiss? What about those moments that wouldn’t fit into anyone’s movie version of their own memories? What does that movie look like?”

“That’s what was interesting to me. Those moments are your moments, they’re your memories. What do they look like? How did they feel? I was going for that. Why do you remember that one weekend? Why do remember that particular camping trip? What was it about that argument that mattered? Of all the things you remember about your childhood why do you remember that? I wanted the movie to feel like a memory. Which, if you think about it, is interesting, because even as we were shooting it – at least early on – we knew we were shooting a period piece even though we were currently in the present. To know you were in the past tense even when you were in the present, it was fascinating. It was such a unique process.”

Linklater pauses for a moment, collecting his thoughts as he tries to put things in even more personal perspective. “I think for the most part you can’t help but reflect your own personality,” he admits. “I think I’m more of an introverted listener than I am an extroverted talker. I’m not that outgoing, necessarily, so I’m a little more contemplative. I think my characters end up a little more like that, maybe.”

As for audiences and how they relate to this particular film, the director knows how he doesn’t want them to feel, even if he’s less certain as to what pieces of his opus they’re going to latch onto the strongest. “I hope they’re surprised that the movie doesn’t feel like an experiment,” says Linklater with a shrug. “It sounds like one, I think, but I don’t want people coming out after watching it feeling like that’s what it was. I hope that they’re surprised that they are pulled in on a narrative flow. I’d like them to be talking about how they related to it, there’s so much commonality. We’re so much more similar than we are different, and that’s what it means to be human, and I hope people find that common ground between one another as it relates to growing up. Which pieces will resonate strongest for them? That I can’t begin to know.”

As for his own plans and where he goes from here, that’s a little less certain. Not that Linklater’s complaining. “I’ve got a lot of things I’m trying to do,” he admits with a knowing, somewhat sheepish grin. “The thing about doing this for so long, I have a big backlog. Early in the career it was always going from the next film to the next film to the next film, but over time a couple of them don’t happen, they get put on the backburner. I’ve spent a lot of time writing and developing different things, and there are so many ideas I’d like explore, so I’ve got a decade-long backlog of things I’ve been trying to do.”

– Interview reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle