Tragic Fruitvale an Emotionally Explosive Exposé

You can’t walk away from seeing Fruitvale Station without being affected by it. Manipulative? Probably. Agenda driven? I guess you could make that case. Showcasing only one side of an explosively complicated and controversial story? Sure, more or less, but in some ways that’s the point.

The simple truth is that writer/director Ryan Coogler’s film packs a mighty wallop, and any sort of criticisms you want to throw its direction don’t really stick because the central themes it’s exploring and the emotions it is mining always feel real. If it is one-sided, if it does only have one point-of-view, that is entirely by design, the filmmaker showing how the potential for change, rebirth and personal growth can be cut down in an instant thanks to unforeseen acts of prejudice and fear. It is a story of what might have been but sadly was not, reminding everyone of a shot that stunned a city and a country but was then, like so many similar stories, quickly swept under the rug and forgotten, few, if any, lessons learned afterwards.

It is January 31, 2008. It is his mother Wanda’s (Octavia Spencer) birthday and 22-year-old son Oscar Grant (Michael B. Jordan) wants it to be special. He’s grabbed three lobsters for the event even though he’s secretly lost his job at a local Bay Area grocery store, keeping this secret from his long-suffering girlfriend Sophina (Melonie Diaz), mother to the pair’s beautiful four-year-old daughter Tatiana (Ariana Neal). But even though he’s in desperate need of money, even though things are tight, he’s making a resolution to be a better father, a better son, a better man, maybe even potentially a better husband (if she’ll have him), these resolutions all perfectly suited to a New Year’s Eve overflowing with possibility.

One day, save for a few key, tragically important flashbacks, is all that is covered in Coogler’s brief, barely 90 minute, documentary-like drama, but that’s more than enough for the story to hit home. Never pulling its punches, fearless in its approach to paint as true a picture as it can, the director does not sugarcoat, doesn’t attempt to color things in lights outside of grey.

Oscar had his faults, he was not perfect, his young life filled with bad decisions keeping him from realizing his full potential. But it is that potential, his apparent willingness to change, to be the type of father, son and husband those in his life could be proud of, that was ripped away from him early in 2009, Bay Area BART officers making judgments based entirely on how he and his friends looked and acted and not based on the situation itself. They erased Oscar, canceled out any chance he had to live up to being the man his mother dreamt he would be, and as such showed that America, as far as Race is concerned, hasn’t progressed near as far as some, mainly those of an extreme Conservative perspective, would like us all to believe.

Coogler isn’t hiding anything. In the opening minute he reveals the outcome, so when the end comes it can hardly be considered a surprise. Yet even though he reveals his cards to the audience that doesn’t lessen the overall impact. If anything, it somehow increases the enormity of it all, and as soon as the BART train leaves downtown San Francisco to head back to Fruitvale the lump growing in the pit of my stomach suddenly tripled in both weight and size. Knowing what was going to happen didn’t lessen the tragedy, it magnified it, Oscar’s redemptive struggles ended even before they had the chance to begin.

Spencer is mesmerizing, her supporting turn (she also co-produced the film) one of conviction, resilience and fortitude making her moment of insoluble regret all the more powerful. For those that felt the Oscar-winner only had one side to her, could only give performances like her one from The Help, here is proof she is far more dexterous and talented than some would give her credit for being. The multilayered nuances of her portrayal is staggering, the actress delivering an unforgettable portrait of motherhood that continually speaks volumes even if all Spencer is doing is raising an eyebrow or allowing her shoulders to droop in agony.

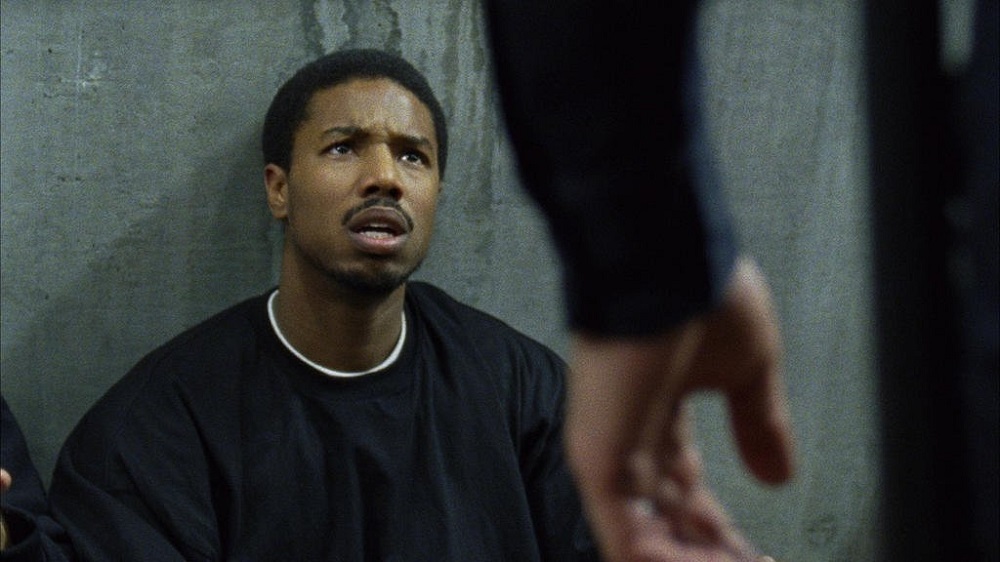

Then there is Jordan. Solid in Chronicle, best known for his work in both “Friday Night Lights” and “The Wire,” he is something of a minor revelation as Oscar, the majority of the film zeroed in on him and him alone. He is playful, sincere, angry, damaged, loving, regretful and so much more, often times in the very same scene, the actor delivering as complex a portrait as any I’ve had the pleasure to witness this year. He doesn’t pull back, doesn’t attempt to hide Oscar’s failings just as much as he allows himself to revel in the young man’s successes, scenes between him and Neal, just terrific as Tatiana, crackling with a genuine exuberance that’s as fresh and as exciting as a morning’s first rays of sunshine.

Fruitvale Station will undoubtedly be seen in context of current events, and in many ways that’s both to be expected as well as perfectly fine. But on its own, as a stand-alone release depicting a tragic true story with candor, grace and realism, Coogler’s movie makes as indelible an impact as anything I’m likely to see in all of 2013. Whether there’s an agenda or not, the film’s core message is one we could all to take a lesson from, the tragic consequences of continuing to not do so loudly, angrily and, most depressing, violently speaking for themselves.

Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)