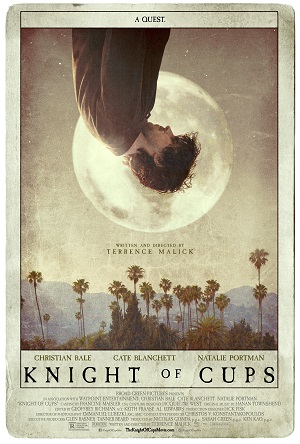

Knight of Cups (2016)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - March 9th, 2016 - Four-Star Corner Movie Reviews

Malick’s Cups an Esoteric Jolt of Pure Cinematic Imagination

Knight of Cups is writer/director Terrence Malick at his most lyrically esoteric. If his last film, the atmospheric, if claustrophobically nondescript saga of love and woe, To the Wonder, was the acclaimed filmmaker’s attempt to pick away at cinematic convention, it is with this one that he abandons traditional narrative constructs entirely. He has officially entered into Jean-Luc Godard terrain here, and much like that legendary filmmaker’s last effort Goodbye to Language, Malick comes as close to crafting a purely visual, impenetrably obtuse tone poem about the human condition as anything I could have imagined beforehand.

If this were a traditional narrative construct, Knight of Cups would be about hedonistic Hollywood screenwriter Rick (Christian Bale) attempting to make sense of his life in the wake of his youngest brother’s untimely death. He’d be dealing with an aging authoritarian father (Brian Dennehy), another brother (Wes Bentley) struggling with addiction and an estranged mother (Cherry Jones) who wants nothing to do with her psychologically damaged ex-husband. Rick is also working his way through a variety of women, including the one who by all rights should have been the love of his life (Cate Blanchett), while another he bares his heart and soul to (Natalie Portman) happens to already be married. In between them are a series of actresses, models and strippers (Freida Pinto, Isabel Lucas, Teresa Palmer, Imogen Poots), all of whom feed his need to be loved and cared for as he gives them in turn a sense of freedom from responsibility they likely haven’t known since childhood.

This, however, is not the version of that story. Malick has attempted to manufacture something far more ephemeral, but at the same time much more intimate, than that relatively simple, overly familiar melodramatic scenario would initially lead one to believe. What the movie becomes, then, is a treatise on self, a memorandum on faith, things moving in a dreamlike fashion where memory and experience collide in order to manufacture a present reality that is continually in a state of flux. It is the entire human condition in the continually wandering form of a single man, making choices and decisions that range across the entire good-bad spectrum and as such paints a picture of self that’s as painful as it is joyous, as indescribably unique as it is universal.

Working again with three-time Academy Award-winning cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki (they’ve collaborated on The New World, The Tree of Life and To the Wonder), the movie has a visual aesthetic that stamps it as a Malick production yet also feels inexpressibly inventive. The pair transforms their camera into a de facto voyeur, spending most of the time hovering right over Rick’s shoulder as he traipses through his various situations. It makes the audience the proverbial fly on the wall, a ghostly specter analyzing this man’s every move almost as if they were living inside his skin.

With To the Wonder, Malick could never get the balance right, his intentions slipping too often into pretension, diluting the emotional undercurrents I can only assume he was attempting to hint at in ways that left me frustrated and slightly annoyed. This was a first for me where it came to the director, all his previous motion pictures ones I treasure to my very core, especially Days of Heaven and The Thin Red Line, a pair of masterpieces I feel are two of the greatest films ever made. But Malick’s insistence on traveling into the realm of pure cinema, a stream-of-consciousness style of filmmaking that’s as nondescript as it is ostentatious, didn’t work here, and as such it was hard not to believe the director’s aspirations got the better of him.

Undaunted, Malick goes back to this well with Knight of Cups, and while I am not what anyone would call a spiritual person, not since Darren Aronofsky’s Noah has a movie made me look inside at my own beliefs as they pertain to God, faith and religion with such palpably intimate ferocity. No real story. No obvious character arcs. None of it matters. Rick’s quest is one filled with hardship and pain, something that is eloquently pointed out to him on numerous occasions by religious figures of varying faiths (the most potent of which is portrayed by the great Armin Mueller-Stahl), his struggles ones I found myself relating more and more to as his search went on.

There’s no way for me to know who this film will appeal to and who it will not. Truth be told, considering the nature of the storytelling, the way Malick eschews convention at every turn, it will likely be a scant few who respond as I have, the director on his way to becoming the most abstruse major American filmmaker working today. But his experimentation here excites me, has me looking at my own life in ways I haven’t dared to in quite some time. It makes his latest a superlative triumph that transcends any rational critical analysis I could ever have hoped to throw its way, and while I can’t explain why, Knight of Cups has me flabbergasted; and I’m eager to dive into its metaphorical waves again sometime soon.

Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 4 (out of 4)