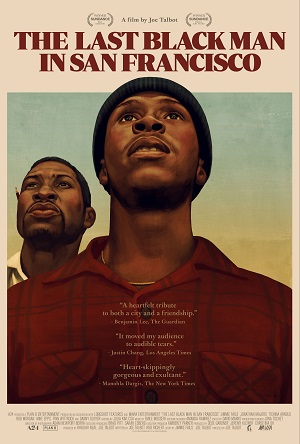

The Last Black Man in San Francisco (2019)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - June 21st, 2019 - Movie Reviews

Insightful Last Black Man in San Francisco an Emotionally Eloquent Triumph

In the Filmore district of San Francisco sits a house. It is a massive Victorian, one reportedly built in the 1950s by iconoclast dreamer Jimmie Fails’ grandfather. But his father James Sr. (Rob Morgan) lost it while he was still a child, all of the antique furniture and their most prized possessions currently stored in his aunt Wanda’s (Tichina Arnold) basement. Now sharing a room with his best friend Montgomery Allen (Jonathan Majors) in his grandfather’s (Danny Glover) cramped abode on the outskirts of the city, much to the consternation of the elderly pair now living there Jimmie heads downtown on a regular basis to do maintenance on his childhood. Montgomery joins him on these outings, chronicling every aspect of their many adventures in a hardbound notebook in which he is constantly scribbling.

After an unexpected confluence of events, the house in the Filmore district suddenly sits empty. Grabbing all the old furniture from his aunt, Jimmie decides to secretly move back in, introducing himself to other homeowners as their new neighbor. He invites Montgomery to live with him, the pair going about attempting to restore the interior to its original glory. But things do not go entirely as planned, and it’s never clear that the two friends should be setting up residence with such cavalier certitude in the first place.

There’s a lot going on in director Joe Talbot’s Sundance Film Festival favorite The Last Black Man in San Francisco. Loosely born from co-writer/star Jimmie Fails’ own life experiences, the movie is at times a broad comedy, at others a searing social commentary, and in many instances a bracingly tragic melodrama. It is also a hopeful aria about letting go of the past and proceeding into the future undaunted, while at the same time a melancholic remembrance of times gone by and of an iconic American city in the throes of impossibly convoluted transition. Concepts of race, family, friendship, gentrification and economic inequality are all touched upon. This is as unique a motion picture as I’ve seen in 2019, and while not all the pieces fit together perfectly, the emotional response I had to Jimmie and Montgomery’s journey was still staggeringly monumental.

There’s plenty to unpack. There is a tenderness to Jimmy and Montgomery’s friendship that’s unusual and surprising. The latter is quiet, soft-spoken and constantly scribbling notes and drawing pictures in his notebook. The former conveys an equally approachable and laidback demeanor, yet he also has a stoic resolve and brash selfishness that feels diametrically opposite of any of the traits displayed by his best friend. But Montgomery is nowhere near as timid as he appears, while Jimmy’s emotional resolve isn’t as unbreakable as he tries to make it seem like it is. Each man looks out for the other in a variety of ways, most of them so under the radar the other almost isn’t even noticing their friend is doing it.

Much in the same way Blindspotting made Oakland its third main character, this movie does the same with its titular city. Through Jimmie and Montgomery’s eyes we see a changing San Francisco. The effects of gentrification and economic disparity are subtly on display, the extremes between the haves, have-nots and those struggling to find footing sitting smack-dab in the middle difficult to miss. There is a streetwise Greek Chorus of young Black men Montgomery analyzes down to their last detail, and when tragedy shocks everyone senseless, it is the soft-spoken writer who forces an entire community to face how they’re feeling about this death while at the same time making them assess their own culpability in allowing something like this to happen.

Some of the story beats are undeniably heavy-handed. Others feel unfinished and not as completely thought out as I’m almost certain the filmmakers intended them to be. But there is so much heart to this story, so much affection for both the two main characters as well as everyone in the community that they end up encountering as they navigate their way through this crazy indescribable trip they are on. The heartbreak is palpable. As is the joy. Most importantly, the insights, even the ones that feel unfinished, are authentic and pure, the observational articulateness of this tale frequently moving me to the edge of tears.

Fails is very good, while Glover, Morgan and especially a superb Arnold make deep, long-lasting impressions that lingered with me long after I left the theatre. Adam Newport-Berra’s cinematography is a constant revelation, and I was equally astonished by the passionately subtle depth of composer Emile Mosseri’s expressively evocative score. But for me the real surprise was Majors. Montgomery is a fascinating character who only grows in resonance as the film goes on. Majors builds his performance with hushed vitality, his titanic explosion near the film’s climax an absolute stunner. The actor has a magnetically soulful eloquence that blew me away, his and Fails final scenes so intimately terrific I’m certain I’ll be thinking about them for the remainder of the year, all of which helps make The Last Black Man in San Francisco a towering achievement I’m ecstatic to be able to celebrate.

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)