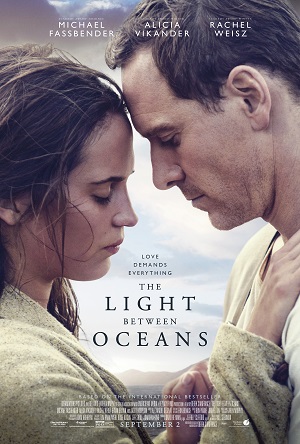

The Light Between Oceans (2016)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - September 2nd, 2016 - Movie Reviews

Poetic Oceans a Swirling Sea of Melodramatic Trauma

Tom Sherbourne (Michael Fassbender), a veteran of the Great War, has come to the outskirts of Western Australia to leave his demons behind. It is 1918 and he longs to be left alone, looking for seclusion and way to journey back from the brink of despair, and he believes he has found it by becoming the lighthouse keeper on the desolate, if beautiful, Janus Rock. But back in the town of Partageuse, the closest point of civilization, he makes the acquaintance of the beautiful Isabel Graysmark (Alicia Vikander). The pair strikes up an intense friendship via their heartfelt and intimate letters, ultimately getting married and allowing her to join him at the lighthouse.

Time passes, and, sadly, although their love is strong, tragedy strikes. Twice Isabel becomes pregnant with Tom’s child. Twice she suffers a horrific miscarriage. But days after the second one, before they can call for a doctor or return her to Partageuse to be checked out, a small dingy washes ashore, and inside a dead man clutches the cold, frigid body of his miraculously still breathing infant daughter. Instead of contacting the authorities, reporting what has taken place, Isabel convinces Tom that they could raise the child themselves, and as no one knows of the second miscarriage, they’ll just believe the baby is theirs.

Based on the best-selling novel by M.L. Stedman, director and screenwriter Derek Cianfrance’s adaptation of The Light Between Oceans isn’t nearly as far removed from his previous pictures Blue Valentine or The Place Beyond the Pines as it might initially appear. It’s another story involving families going through unimaginable personal strife, anxiously trying to find a way to stay together even when the world around them falls apart. Tom and Isabel are good people who are feverishly in love, their connection almost primal in its intimacy. But they make a horrendously bad decision for what appears to be all the right reasons, and as good of people, and as great of parents, as they might be, the suffering that will rain down upon them will, not just be massive, but also deserved.

The good news is that the movie isn’t as unrelentingly downbeat and depressive as Blue Valentine. The bad news is that it tends to drown in melodramatic excess as it limps towards the finish line. Until that point, however, this can be an impressively acted, marvelously shot, superbly designed and lovingly scored motion picture. More than that, it is one that is entirely unafraid of the emotions sitting at its core, embracing the seedier aspects of its character’s more dubious decisions and yet also refuses to put them on trial. It asks the viewer to analyze things from their perspective no matter how uncomfortable doing so might be, understanding the depth and breadth of their passions for one another run even when the world they know crumbles in bruised and battered tatters around them.

The first half is excellent. Cianfrance maneuvers his characters with sublime grace and majesty, getting them where they need to be for the cataclysmic events that cannot help but come. The romantic longings blossoming between Tom and Isabel are natural, even when they develop over the course of letters read in voiceover. The tragedies that effect them are deep, long-lasting, so when the moment comes that they end up making the decision that will rule the rest of their lives on certain internal levels it is oddly understandable. More than that, they are spectacular parents, and as they watch young Lucy grow, help nurture her inherent curiosity in the world around her, I honestly found myself rooting for them to continue on in the job.

But that simply cannot be. The twist comes in the appearance of Hannah Roennfeldt, played to internalized traumatic perfection by Rachel Weisz. It’s no secret who she is, what horrors she has suffered through, and seeing her in such pain and misery one can’t help but hope she’ll find some semblance of peace relatively soon. Yet this can only happen if secrets are uncovered and lies are transformed into truth. It can only happen if loving parents are ripped asunder from the child they have called their own for over four years, opening up new traumas the repercussions of which no one in the entire town of Partageuse are able to predict.

It is here that the movie doesn’t so much lose its footing as it starts to stumble, if ever so slightly, down the path towards its inevitable conclusion. From Hannah’s introduction forward things aren’t always easy to relate to, and seen through a modern lens many of the things that transpire border on frustrating, borderline distasteful. But Cianfrance is a stickler for detail, keeping things grounded in the time period of the story, never judging his characters, allowing their missteps and successes speak for themselves. The inherent emotions do threaten to overwhelm the proceedings, and the director almost can’t help but play them up in ways even Douglas Sirk might have found overly melodramatic. The last 20 minutes or so are especially syrupy, and while they’re as starkly presented as anything else, the overbearing nature of the emotive mechanics are still impossible to overlook.

Be that as it may, Fassbender is glorious, while Vikander is his equal, and even if neither actor appears to be working all that hard to achieve an authentic Australian accent their portrayals of Tom and Isabel are achingly natural. As stated, even with limited screen time Weisz makes the most of every second, and I love her reactions as she contemplates times spent with her late husband and comes to understand all it was he was trying to tell her in their terribly short time together as a couple. Australian legends Jack Thompson and Bryan Brown make an indelible impression in key secondary roles, while the eclectic group of character actors selected to portray the Partageuse townsfolk are aces across the board.

I need more time to think about The Light Between Oceans. My kneejerk reaction is that it doesn’t rise to the same heights as Cianfrance’s previous pictures, that the director, for all his control, confidence and restraint, doesn’t quite know how to bring things home in a way that is entirely sincere or emotionally plausible. Yet, in large part thanks to the performances, not to mention a memorable assist from composer Alexandre Desplat’s (The Danish Girl) exquisite score, there is something about the movie I cannot resist. Like the waves assaulting Tom and Isabel’s lighthouse, there was a constant war being waged for my affections here, and reservations notwithstanding I’m hard-pressed not to say that the film itself deservedly ends up earning them.

Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 2½ (out of 4)