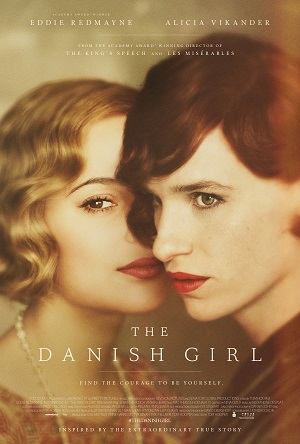

Danish Girl a Gender Journey of Self-Discovery

Rising landscape artist Einar Wegener (Eddie Redmayne) is married to Gerda Wegener (Alicia Vikander), a fellow painter specializing in portraits. They are best friends with renowned dancer Ulla (Amber Heard), going to parties with many of Copenhagen’s most prominent citizenry at her behest on a somewhat regular basis. But Einar feels out of place at these affairs, like he doesn’t fit in, and as such it takes a lot of time and effort on Gerda’s part to oftentimes convince him to attend a single one of them.

A chance opportunity leads to a realization of self and identity that in some ways takes both of them by complete surprise, yet in other ways feels utterly rational when they step back and allow themselves to think more about it. After attending one of Ulla’s events dressed up as a girl, due in large part to Gerda’s prodding, the two thinking of it as a game they are playing to fool the rest of the stuffy and clueless attendees, Einar discovers he doesn’t want to let newfound femininity go. With his wife uncertain of what to do or who to ask for help, her painter husband begins to disappear, a new, dainty creature calling herself Lili slowly emerging in his place.

I saw director Tom Hooper’s (The King’s Speech, Les Misérables) cinematic accounting of Lili Ilse Elvenes, better known as Lili Elbe, The Danish Girl, over a month ago, and in all honesty I wasn’t altogether certain I’d be able to write a review of the film. The Danish Transgender woman was the first known person to go through sexual reassignment surgery, doing so at a German medical clinic in 1930 under the supervision of sexologist Magnus Hirschfeld and carried out by Dr. Kurt Warnekros (portrayed by Sebastian Koch in the film). Dying in June of 1931 from complications from a fourth surgery, which included a potential uterus transplant, a book based on her diaries, Man into Woman, was published in 1933, becoming an instant bestseller.

Based on the 2000 novel by David Ebershoff, The Danish Girl does not claim to be an entirely factual accounting of Lili and Gerda’s relationship, as many of the actual events that propelled them forward on their respective journeys were changed for both creative and narrative reasons. Lucinda Coxon’s (Wild Target) screenplay follows suit, and, if anything, changes things up even more, and as such should not be looked at as a definitive accounting of this pair’s momentous and important adventures in gender. There’s a ton of historical butchering at play in the film, a thing I don’t necessarily have a problem with, but also something I feel should be pointed out at the exact same time.

None of which is why I find this movie so gosh darn difficult to write about. No, the reasons for that are much more personal, as so much of Lili’s journey, even at eight-plus decades after the fact, mirrors so many of the footsteps, conversations and footsteps I myself have taken, trying to react to it in words as it encompasses a critical review is agonizingly difficult. The simple truth is that, while Hooper and Coxon stumble here and there, while the melodramatic entanglements Lili and Gerda end up facing can be on the stilted side, the core events, the items dealing with one person’s gender transformation and the other’s reactions to it, are close to perfect. More, they’re bracingly authentic, a thing I never could have anticipated before walking into the theatre for my press screening.

What’s most remarkable is how confident Hooper and Coxon are in showing just how selfish Lili can be, how taking the giant leap to be herself ends up irrevocably damaging a relationship still exceedingly near and dear to her heart. As Transgender individuals, sadly far too often we hide large facets of our personality out offear of discovery, ridicule and hate, attempting to be what others expect instead of who we know ourselves to be. When we finally embrace our inner selves, the initial gut reaction can be to run towards it not thinking of anyone else around us, and as such this directness of purpose can come across as egocentricity run amok.

This won’t be palatable to some. Most, who’ve never had a Transgender family member or friend, aren’t going to grasp what’s happening, more than likely, and they’ll look at Lili’s treatment of Gerda and shake their head wondering why she’s putting up with it. But this is also what makes Gerda such a stunning character and, in point of fact, arguably the film’s main – and maybe titular – character. In more ways than one this is her story, one where she learns not just to accept who her husband is transforming into, but to embrace it herself, even if she doesn’t entirely understand all of what is taking place. It’s a remarkable tale, one so many families have experienced and embraced, as well as one so many others have sadly turned their back upon. Gerda looks at what is happening to Lili and puts pieces together one after the other; and as hurtful as things might become, the knowledge that the person closest and most important to her can’t continue as-is trumps all else.

It’s the surrounding material that’s a little limp. Hooper and Coxon play it very safe, very traditional as far as the exterior, secondary plot mechanics are concerned, almost as if they realize they’re presenting material some will find uncomforting (even if they shouldn’t) and so they don’t want to make waves with any of the rest of it. It’s all very straightforward, very matter-of-fact, having a BBC television quality that’s moderately forgettable. The movie is also obnoxiously framed in certain moments, much in the same way Les Misérables was, Danny Cohen’s (Room) camerawork getting so in the face of some of the characters you can almost count their nose hairs.

Redmayne is superb, delivering a delicately nuanced performance that’s easy to relate and respond to. But as great as he is, the real star here is Vikander. In a year where she’s already been wonderful in Ex Machina, Testament of Youth, Burnt and The Man from U.N.C.L.E., what the actress does here is extraordinary. Her Gerda is a breathtaking creature, watching her come to life so intricately, with such complexity, a real joy. Vikander is electric and alive, a spectacular lithe and limber creature of elegance and understanding who only grows in importance and impact as events progress.

But it’s the fact that The Danish Girl gets the core stuff right that makes it important, and equally difficult for me to talk about. While I wish the movie didn’t play so fast and loose with many of the facts, Hooper and Coxon have still structured a story of self-acceptance and discovery that transcends its historical inaccuracies and allows it to ascend to a level of magnetic emotional resonance I found impossible to resist. It understands sex and gender are not the same thing, and that the former isn’t a binary construct that only allows for two norms. The options are endless, and the fact the film not only embraces this, but celebrates it, makes it as important a piece of a cinematic entertainment as any to be released this year.

Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3 (out of 4)