Well-Made Mid90s Inauthentic Cultural Tourism

Stevie (Sunny Suljic) is a wide-eyed 13-year-old living in Los Angeles with his single mother Dabney (Katherine Waterston) and abusive older brother Ian (a suitably belligerent Lucas Hedges). Not sure what exactly it is he’s looking for, one day the youngster spies a group of kids skateboarding in front of a downtown store. Getting up the guts to wander into their skate shop, Stevie is surprised by how quickly this tight-knit group welcomes him as one of their own. Soon he’s hanging with them all the time, learning to skate, going to parties and stirring up all types of trouble. It’s all part of a wild 1995 summer Stevie, his new friends and his family aren’t soon to forget, the memories that are going to be made certain to last all of their respective lifetimes.

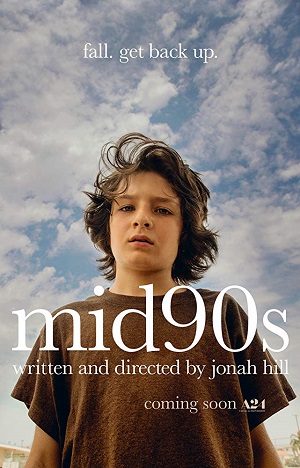

The directorial debut for actor Jonah Hill (who is also wrote the film’s script), Mid90s feels like something of a well-composed, authentically acted Kids knockoff (which just so happened to be released in 1995) more than it does anything else. Filled with as many troublesome scenes as it does emotionally affecting ones, the movie is akin to something resembling a well-intentioned vanity project but one that is filled with observations that are too obvious, too facile and far too underdeveloped to resonate on the level I’m almost certain Hill intended them to.

Suljic, last seen to such devastating effect in Yorgos Lanthimos’ The Killing of a Sacred Dear, is admittedly a fascinating young talent. Stevie is searching for friendship, he wants a father figure as his brother is too destructively violent and too overflowing in self-loathing to fit the bill, and watching him bond with this group of skateboarders isn’t without its various pleasures. Suljic brings a winning innocence to his performance that’s haunting, and as he keeps doing whatever he can to fit in and become one of the group the emotional cost of each new experience or situation is innately devastating. The young actor is nothing short of remarkable, and as many reservations as I have with the film as a whole his spellbinding work as the story’s protagonist thankfully is not amongst them.

I also liked the collection of non-actors, Na-kel Smith, Olan Prenatt, Gio Galicia and Ryder McLaughlin, Hill assembled to portray the skateboarders. Their collective friendship, including all of its hardships, feels authentic, each actor able to make the script’s dialogue their own and in the process give it a lived-in authority it likely wouldn’t have had otherwise. At the same time, I also didn’t feel as if any of them were portraying fully-formed, three-dimensional characters but instead were nothing more than inner-city street kid archetypes, each a various trope who only exists to help Stevie’s story move towards a conclusion. Smith, masterfully portraying the group’s most talented member and erstwhile leader, is particularly stuck between a rock and a hard place, and while his character Ray is the most magnetic and intelligently nuanced of the quartet he is also a stock piece of cliché who comes perilously close to being the offensive “magical negro” stereotype straight out of What Dreams May Come, The Green Mile or The Legend of Bagger Vance.

Thankfully Hill doesn’t take Ray quite that far, allowing Smith ample freedom to try and give the character an inner complexity that isn’t in the script. But that the director still gets close to this risible stereotype is in and of itself problematic, as are moments in the middle of the film where Stevie joins the gang at a late-night party where they’re joined by a gaggle of junior and senior-aged teenage girls. What follows is a moment between two drunken children in a closed room where some sort of initial sexual exploration takes place involving Suljic and Brigsby Bear and “Ray Donovan” actress Alexa Demie. I honestly don’t have a problem with what Hill is showcasing here. Stuff like this happens. We all know it whether we want to acknowledge it or not, and I imagine a lot of our own first forays into sex weren’t as different as we’d like to admit.

The issue is that I’m not entirely certain Hill has any concept of what it is he’s showing or why it is so disconcerting. There is a veiled sexism in this exchange that’s unsettling, the way Demie’s character is portrayed as some sort of hypersexual manic pixie dream girl who only exists to make Stevie’s heretofore unknown fantasies come to life understandably rubbing me the wrong way. It’s like all of this is some sort of hardscrabble piece of street kid wish fulfillment and nothing else, Hill seemingly more content in crafting images of this world than he is in finding the hard, harsh truths residing within it.

Juxtapose all of this with something like Andrea Arnold’s American Honey or Sean Baker’s dual whammy of Tangerine and The Florida Project, and for all its narrative passion and visual eloquence (vaunted cinematographer Christopher Blauvelt shoots things with a magnetic attention to detail that’s riveting) Mid90s almost can’t help but come up short. Unlike Baker or Arnold, neither filmmaker exactly born and bred in the worlds their stories were depicting, Hill feels like more of a tourist just visiting these neighborhoods than he does a passionate cinematic anthropologist excited about studying them in a realistic way. His attempts at analyzing and dissecting this culture have no resonance, no deeper meaning, all of which makes his handling of Stevie’s summertime adventures come off as inauthentic. For all his obvious skill behind the camera, Hill’s debut left me too anxious, questioning and somewhat angry for me to be able to feel comfortable extolling any of its many virtues, and even if I reassess those feelings at some point in the future I honestly don’t see them changing anytime soon.

Film Rating: 2 (out of 4)