Stewart’s Rosewater Intriguing Look Inside Modern Iran

In June of 2009 London-based freelance journalist Maziar Bahari (Gael García Bernal) returned home to Iran to cover the election of the country’s new president while on assignment for Newsweek magazine. In the aftermath of what proves to be the controversial re-election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, and during the riots and displays of public disobedience that followed, a group of policemen come to his mother’s (Shohreh Aghdashloo) home to question him. Not long after, the journalist is arrested and sent to the notorious Evin Prison with no reason given.

Bahari will spend the next 118 days being questioned under the most extreme conditions by a man (Kim Bodnia) he only can recognize by the smell of the rosewater he scents himself with. Completely isolated, cut off from the world, he believes he is entirely alone and at the mercy of his captors, only the thought he’ll be reunited with his pregnant wife Paola (Claire Foy) back in London keeping him from fully succumbing to depression and despair.

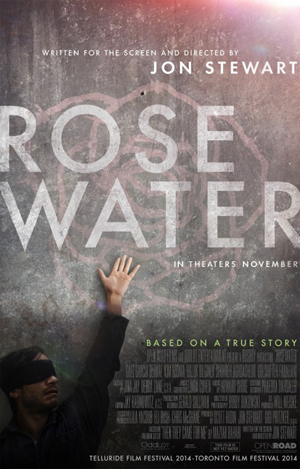

Based on Bahari’s own accounting of the events that took place inside Evin (co-written with Aimee Molloy), “The Daily Show” creator and host Jon Stewart makes his directorial debut with the docudrama Rosewater. In many ways this makes a lot of sense as one of the items held against the imprisoned reporter was the fact he’d appeared on this show and participated in one of its skits. I feel fairly safe in surmising this is a tale near and dear to Stewart’s heart, and that passionate attention to detail is visible in virtually every frame of the finished film.

As strong as many of the individual pieces might be, as impressive as certain sequences are, there is an oddly distant aura permeating the picture that’s difficult to get past. So much of what transpired kept me surprisingly at arm’s length from an emotional standpoint, the trauma of Bahari’s ordeal not coming through as clearly or as intimately as I kept hoping it would. It is almost as if Stewart’s approach is too clinical, too journalistically detached, making the final moments unable to hammer themselves home as deeply or in as thought-provoking a manner as they needed to in order for the film to ascend to the next level.

Still, Stewart’s debut is impressive on multiple fronts. His script is clean, orderly, focused with razor-sharp precision on Bahari and all that it is he is going through. All of significance that transpires is seen through his eyes, from his vantage point, allowing the breadth and scope of what is happening in Iran during this election to carry far more weight and meaning in the process. There is ample insight to be found in many of the film’s quieter, more intimate moments, and while the full picture is never entirely ascertained enough of it is to give the story a subtle grace that’s continually fascinating.

The film loses its way whenever it strays from Bahari, especially the times it focuses more on Rosewater and who he is. It’s an attempt to humanize him, show how all of this is affecting the interrogator. Problem is, he’s not enough of a three-dimensional figure for these sequences to feel like anything more than thinly crafted guesses as to who this guy might be and what his life might potentially be like. They don’t carry any oomph, no zest, this mysterious figure remaining too ephemeral a creature for us to feel any sort of emotion, positive or negative, about whatsoever.

Bernal, on the other hand, is excellent, delivering a full-bodied, completely immersive performance that’s a continual joy to behold. In many ways his Bahari makes a terrific companion to his René Saavedra, the protagonist in the equally explosive political docudrama No(that film chronicling a 1988 Chilean referendum that changed the face of the country). At the same time, this is an entirely different sort of character, his transformation from relative political neophyte, to crusading journalist, to unjustly imprisoned husband and soon-to-be father desperately trying to hold onto his fracturing sanity utterly believable every step of the way.

Stewart doesn’t do a lot with Aghdashloo, and it’s a testament to the Oscar-nominated actress’ talents that she ends up being as memorable a presence as she ultimately ends up becoming. As for Foy, I’m honestly not sure why she’s around as much as she is, and while Paola’s part in her husband’s eventual release is important as far as this film and this story is concerned all she does is slow things down to a crawl whenever she appears. If anything, the director does a better job integrating real news footage into the proceedings, adding a level of verisimilitude into the drama that likely wouldn’t exist otherwise.

There’s a lot to love about Rosewater. Bernal is superb, the story is one deserving of the spotlight while the film itself grants a look inside modern Iran most could barely fathom let ever hope to see. Stewart shows a lot of promise as a filmmaker, especially as far as his screenwriting is concerned, and even with all of my nitpicks I can’t say I ever felt any of the narrative mechanics were ever outside of his control. Yet I was never as emotionally invested in Bahari’s travails as much as I felt I needed to be, and as impressive as many of the elements driving this picture might be the overall impact is still far more muted and subdued than it by all accounts should have been.

Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 2.5 out of 4