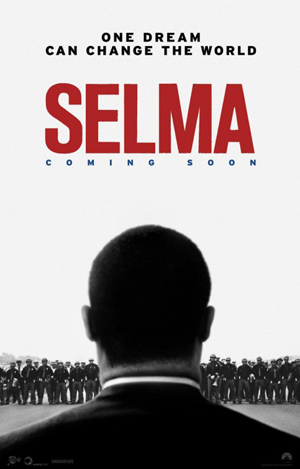

Inspiring Selma Brings King to Life

You know going into Selma that this is a film wearing its supposed importance on its sleeve. As what is essentially the first motion picture to offer a narrative approach to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and times, focusing on his landmark attempts to organize a peaceful march from Selma, Alabama to Montgomery, Alabama in 1965, it goes without saying director Ava DuVernay’s (Middle of Nowhere) latest will offer up plenty of food for thought.

That it doesn’t crumble under that weight is close to extraordinary. That is goes above and beyond any and all expectations even more so. DuVernay does not flinch, does not give in, and working in glorious tandem with screenwriter Paul Webb and actor David Oyelowo she paints a shrewdly devastating picture of progress, resistance, and restraint that held me spellbound first moment to last. It is a movie that weaves fact and fiction in ways that are seamless and inspiring, dramatizing events in ways that broaden one’s understanding of deeply complex issues that still resonate through the country – the world – today.

At the heart of things is Dr. King’s (Oyelowo) disgust for what is happening in relation to voting rights in Alabama and it’s coupled with the State’s rigid refusal, under the director of Governor George Wallace (Tim Roth), to adhere to recently passed Civil Rights legislation. President Lyndon Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) is reticent to get involved for political reasons. It isn’t that he doesn’t agree with Dr. King’s position, he claims he does, it’s that he has other issues on his plate including a proposed war on poverty as well as current events in Vietnam, and pushing through additional legislation in regards to voting rights isn’t a battle he’s sure he has the wherewithal to currently fight.

And thus we are off, DuVernay and Webb thrusting the viewer into the middle of this social and political maelstrom showcasing how the Civil Rights pioneer was able to manufacture support for a massive protest, which would change the face of Alabama, as well as the South as a whole, for generations to come. We see him meet with supporters, engage in debate with detractors and weigh the pros and cons of continuing plans to stage the Selma to Montgomery march. The filmmakers make Dr. King three-dimensional, complex and, most importantly, human, a man of strengths and weakness doing his best to balance the two as he sets out to do what he feels is right.

Issues of historical fidelity aside, most of those having to do with how President Johnson is portrayed and how he is reluctantly cajoled into action by Dr. King, the movie cuts right to the heart of the matter in the briefest, most elegant of brushstrokes. DuVernay refuses to slather the film in unnecessary layers of melodrama, utilizing a documentary-like approach that fits things perfectly. More than that, she keeps the focus exactly where it needs to be, seeing events entirely through Dr. King’s eyes, and even when the narrative drifts to secondary characters it all comes back to him, his approach, his ideas, his hopes and his fears, every single time.

Oyelowo is stunning. Asked to do the impossible, he becomes the Nobel Peace Prize-winner in every detail, not getting caught up in trying to impersonate his mannerisms, vocal tenor or inflections, but instead doing what he can to paint a complex, full-bodied portrait that would do the man, as well as the film itself, justice. He isn’t afraid to show emotion when necessary just as he is apt to put on a face of stoic resolve, allowing it all to melt away when confronted with stark realities and bitter truths especially as they pertain to his relationship with his wife.

Those might be the film’s best moments, those one-on-one, quietly introspective scenes between Oyelowo and Carmen Ejogo, portraying wife Coretta Scott King. A sequence between the two of them responding to the unspoken realities behind a disgusting phone message is shattering in its eloquence, while a later scene outside an Alabama courtroom is as tender and authentic as it is poignant and sincere. Both actors shine, giving themselves over completely to DuVernay and her vision, the movie all the more magnificent because of this.

I want to say there are some issues, and there most definitely are a couple, not the least of which is the almost comical, borderline cartoonish depiction of racist villainy as it pertains to Wallace (made palatable thanks entirely to Roth’s driven, wholly focused performance), but in the end they don’t matter terribly much. The film is so invigorating, so expertly constructed and made – Bradford Young’s (Ain’t Them Bodies Saints) luminous cinematography is exquisite, Spencer Averick’s (Middle of Nowhere) meticulous editing sublime – that its missteps feel so minor they might as well not exist.

In the end, though, this is DuVernay’s showcase, and the reasons behind my feeling she’s done such an extraordinary job is due to the fact her hand shepherding things to the finish line is close to invisible. At the same time, no moment is false, no beat feels out of step with the interior rhythms of the picture itself, her controlled, confident touch delicately driving things in ways that are intimate, subtle and beautifully heartfelt. Selma is an important movie, yes, but it is also a great one.

Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 4 (out of 4)