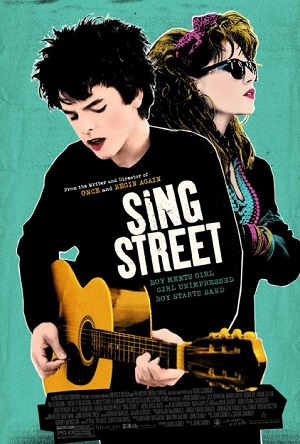

London’s Calling in Carney’s Tuneful Sing Street

Dublin. 1985. Conor (Ferdia Walsh-Peelo), at 15 the youngest of his three siblings, has just learned from his feuding parents (Aidan Gillen, Maria Doyle Kennedy) he is being sent to Synge Street, an inner-city church-run institution light years removed from the posh private school he’d up to now been attending. Forced to walk around in his socks due to wearing the wrong shoes, picked on by the school bully Barry (Ian Kenny), things go from bad to worse within the first few days, only the pint-sized Darren (Ben Carolan) willing to make friends with the new kid.

Things change the moment Conor spies 16-year-old Raphina (Lucy Boynton). She’s got dreams of running away to London to become a model; and showcasing a bit of spunk and a few more ounces of courage than he’s ever exhibited before, the lad doesn’t just introduce himself to her, he also sells the fellow teen on the idea of appearing in his band’s first music video. Problem is, Conor isn’t in a band, at least not yet, but he’s not a going to let a little thing like that stop him. With Darren helping him out, and with some good old familial advice from older brother Brendan (Jack Reynor), this kid is going to do the impossible, maybe discovering hidden talents he didn’t even know he possessed in the process of doing so.

Writer/director John Carney is the mastermind behind Academy Award-winner Once, a film I consider to be a modern masterpiece, and 2013’s sublime musical New York fairy tale Begin Again. His third film, the coming-of-age Irish frolic Sing Street, fits right inside the acclaimed filmmaker’s wheelhouse, and while I can’t say he’s stretching himself all that much here that doesn’t make Carney’s latest any less sublime. If anything, this is a rollicking pop music extravaganza with so much life and heart enjoying it is a virtual impossibility, the director stealing my heart with such confidently raucous abandon I almost don’t even know where to start.

The sense of time and place that Carney is able to construct is astonishing. A couple historical hiccups notwithstanding – there’s a big thing made of Duran Duran’s video for their 1982 hit “Rio,” while Back to the Future is heavily referenced even though it wasn’t released in Ireland until late December of the year the film is set in – the film lives and breathes the ‘80s like few similar films have. More than that, it plays with the musical experimentation of the decade in a way that is fresh and exciting, allowing Conor to evolve and find his signature voice with every new band he discovers.

Even better is the spirit of brotherhood the filmmaker is able to craft, specifically between Conor and his twenty-something sibling Brendan. Their relationship is, somewhat surprisingly, the crux around which the majority of events revolve, the two of them growing closer as things progress towards their conclusion. The byplay between newcomer Walsh-Peelo and rising star Reynor is sensational, building in intimacy and understanding throughout, leading to truthful revelations that are natural, unforced and by all accounts perfect.

I wish Carney had spent almost as much time fleshing out the pair’s sister, middle child Ann (Kelly Thornton), as she’s sort of left to dangle in the wind as an afterthought more than she is anything useful. As to the band Conor assembles, other than instrument prodigy Eamon (Mark McKenna), the majority of them are never all that fully fleshed out or given a personality of their own. While the montage showcasing how they are assembled is winning, there’s just not enough time spent on bringing them together as a singular unit, their commitment to one another more implied than it is anything else.

These should be big problems. That they are not is reason for celebration, Carney managing to overcome his story’s more egregious shortcomings with fizzy, stimulatingly energetic ease. The songs, written and composed by the director and former Danny Wilson frontman Gary Clark (known for the 1987 hit “Mary’s Prayer”), span a number of genres and influences yet still feel right at home inside the era. The most infectious of the bunch, the lively “Drive It Like You Stole It,” deserves to be a smash right this very second, while the beautifully poetic “To Find You” has a simplistic, knowing grace that moved me almost to the point of tears. Best of all is the chemistry between Walsh-Peelo and Boynton, the pair lighting up the screen, managing to craft a realistic depiction of friendship and blossoming young love that’s universally timeless.

Carney continues to be one of the more inspiring and invigorating filmmakers working today. He has an uncanny ability to mix music and drama in ways that invoke the spirit of the old Hollywood masters of the 1940s and ‘50s, yet at the same time also feels fresh and original for today’s audiences. Sing Street, while not telling a tale that could be labeled as anything close to original, still crackles with an innovative vitality all its own, making its climactic leaps into the starry-eyed unknown all the more wonderful because of this.

Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)