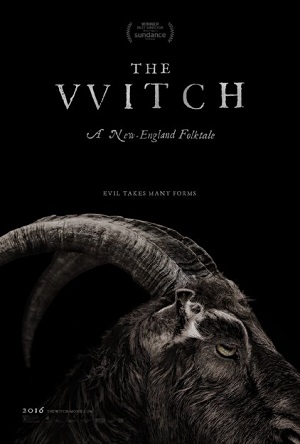

“The Witch” – Interview with Robert Eggers

by Sara Michelle Fetters - February 18th, 2016 - Interviews

Closer to Myth

The Witch Writer/Director Robert Eggers Talks About His Horrifying Award-Winning Debut

Roughly a year ago, Robert Eggers took home the Best Director prize at the 2015 Sundance Film Festival for his historical horror-thriller The Witch. The story of a colonial New England family beset by a strange, supernatural force intent on tearing them apart from within, the movie is a cagy stunner that dissects religious fundamentalism and familial dysfunction in terrifically unsettling ways. Shockingly complex, uniquely character-driven, this motion picture defies easy categorization as it makes its way to its explosively terrifying conclusion, more than living up to the hype that’s been following it around since last January.

A native New Englander, the filmmaker dove right into the research as he started to piece together his ideas for the film, many of the historical nuggets he discovered letting him know he was heading in the right direction. “I think what the biggest lightning bolt, which is the crux of the film, is that the understanding that the real world and the fairytale world were the same for everyone save the extreme intelligentsia,” explains Eggers. “In the court records, the Elizabethan and Jacobean witch pamphlets that are like the historical accounts, it’s the same as these fairy tales and folk tales.”

“I think, in a post The Crucible world, the way we talk about witch hunts, we very much think those who were called witches, the people didn’t believe that. Maybe the people who were peasants did, but the religious leaders they were just trying to get rid of women who bothered them. It’s all about the fear of female power. Absolutely. But it was so extreme, this fear, that many really believed that these were fairy tale witches capable of doing all the horrible, bestial, primal things that the witch does in my film. That really put it all together.”

This research fed ideas and feelings Eggers had been pondering since childhood. “I had witch nightmares ever since I was a little kid,” he says with an uneasy chuckle. “Very archetypal and intense nightmares. So I always had my own ideas of the mythic past of New England. Somehow, the understanding the overall general cultural consensus of the 17th century was closer to my understanding of witches as a kid was kind of interesting.”

All of which playing into a feeling that The Witch needed to be a period piece, that the only way this story could be a success was to have it live and evolve within the same era of history he had been researching. “For me, [this] kind of witch, maybe there is a good way to do this story set today, but for me it was essential to go back to a time where everyone just believed in the idea of an evil witch,” he explains. “This wasn’t even a belief. It was a given. A tree was a tree. A rock was a rock. Was just how it was.”

“It was fun, also, to go back to the very, very beginning of the Great Migration because this was a brief period of North American history where it was almost like the Middle Ages. More, to think about the parents in this film, they would have grown up under the rein of Queen Elizabeth, and that’s so weird in a way to think about. These were English people, who didn’t know how to do anything, totally vulnerable, and they were these extreme religious refugees became obsessed with this idea of living in a new world.”

Not all of the inspirations came straight out of New England folklore and fairy tales, however. “I know a lot of this witch stuff is thanks to Margaret Hamilton,” states Eggers with a happily mischievous grin, name-dropping The Wizard of Oz actress who created one of the great cinematic villains of all-time. “Today, it’s maybe laughable, but at 4-years-old, when Dorothy is in the witch’s castle and she sees Auntie Em in the glass ball and then the face of the Wicked Witch appears, I was like, F-that. It was terrifying.”

“But I also watched Hammer horror films and stuff like that, because, films like A Nightmare on Elm Street, Halloween and Friday the 13th? They always scared me too much as a kid. I mean, Pinhead? He scared me way too much. I couldn’t handle it.”

There are other influences that can be felt inside the film as well, ranging from The Crucible writer himself Arthur Miller, to Pan’s Labyrinth lyricist Guillermo del Toro, to Stanley Kubrick and Ingmar Bergman, two legendary auteurs who both knew how to twist an audience’s emotions into pretzel-like knots. “Ingmar Bergman and Carl Theodor Dreyer, I bow down to them every day,” proclaims the filmmaker. “Bergman is my big hero, but I do also think this movie is very The Shining scented. When it works for people, I think those associations might be a part of that.”

“But The Shining was one of those films I watched a ton in my early to mid-twenties to understand how to make a good film, how you learn to sustain tension for so long. I think some of that was bound to rub off in big ways.”

What is good horror? “It all depends,” says Eggers with a shrug. “I’ve had journalists tell me that this isn’t a horror film, that it’s a psychological suspense thriller with supernatural elements, and I’m like, okay, that’s cool, I guess. Certainly, what’s interesting to me, and what I call horror, one thing is to explore what is dark in human nature, shining a flashlight on that and then run away giggling. That’s paramount to me.”

“As the filmmaking goes, it’s about having restraint. I can’t look into your soul. I don’t know what is the most scary to you so I have to hope that I can depict what is most personal and scary to me and then hold back and let the last bit be something that you fill in yourself. That’s the idea.”

The idea of restraint and what it does to the audiences as it pertains is an interesting topic, especially considering that, for as ephemeral and indistinct as The Witch can be, it also states upfront that there is a supernatural presence in the forest, and that she is hungering for the souls of the family who’ve taken up residence next to its borders. “Maybe I’m giving myself too much credit, but I think with the film that I made that you can look at things literally or not even with the amount I show the witch,” explains the director. “If that doesn’t work for you, I guess all I can say is I’m sorry.”

“But it was always my intention from the beginning to show the witch right away. Most people don’t know what a 17th-century witch is. I needed people to know what were the stakes, what everyone was up against immediately. There was a lot of deliberation whether this was a good idea or not, but it was always important to me. I think it was Jung who said, and if it wasn’t Jung it might have been Anthony Hopkins in a bad horror movie, just because you don’t believe in the devil doesn’t mean you are safe from him.”

All of which could lead one to think Eggers is using this tale of 17th century terror in order to engage in a broader form of commentary, one talking about religious fundamentalism, not just of the colonial period of U.S. history, but also of right this very second in the modern world as we know it now. “I don’t want to be the snobby, erudite, toolbag director and say I was trying to do any of this without any sort of judgment,” he says with a shrug, “but I wasn’t. I’m certainly not trying to condemn religion.”

“I love my Puritan family. Doing the research, Christianity? Having read the Bible so many times? It’s not hard to understand why people like Jesus Christ. It was, however, hard for me to see what people saw in extreme Calvinism. It was impossible to see how Predestination could have been helpful for anyone. This is heavy-duty stuff! Reading diaries and journals, though, you see these people as people. You see people struggling. It’s hard not to care about them.”

And what does Eggers want people talking about after they’ve watched the film? “I think what A24 gets is that I was trying to make a pre-Disney fairy tale,” he states unequivocally. “These pre-Disney fairy tales, they aren’t moralistic. They are not simple. It’s not about what’s the point of it all, it’s how it makes you feel. These older fairy tales, they’re closer to myth.”

– Interview reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle