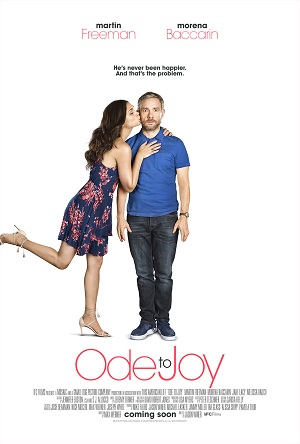

Problematic Ode to Joy Hits Too Many False Notes

Brooklyn librarian Charlie (Martin Freeman) is not a happy man, and that’s entirely by choice. He’s a rare individual affected by narcolepsy with cataplexy, and if Charlie ever experiences giant emotional mood swings he can immediately pass out right there on the spot. This is unquestionably dangerous, but that doesn’t mean he still can’t live a full and vibrant life, his younger brother Cooper (Jake Lacy) certain his sibling could find lifelong happiness with the right person if he would just take a slight risk and put himself out there.

Opportunity arises one random afternoon in the form of the impulsive and beautiful Francesca (Morena Baccarin). Charlie is smitten, and she finds him attractive, too, but even though they have an instantaneous emotional connection he still worries his odd medical condition is destined to doom any chance of a relationship long before it has the chance to blossom. Instead, he convinces Cooper to start dating the young woman instead. This way, Charlie can be around Francesca with no chance of feeling joy or euphoria, the sight of his brother romancing the one person he’s ever been most attracted to certain to keep any chance of personal happiness delightfully at bay.

Partially inspired by a true story first broadcast on WBEZ Chicago’s “This American Life” in June of 2010, screenwriter Max Werner’s (Fun Size) and director Jason Winer’s (Arthur) well-intentioned if still moderately distasteful romantic comedy Ode to Joy is one strange little motion picture. Featuring a couple of strong performances from Freeman and Baccarin, some nice supporting moments from an always luminous Jane Curtain (as Francesca’s cancer-stricken Aunt Sylvia) and a scene-stealing turn from a terrific Melissa Rauch as Bethany, a young woman whose temperament and demeanor is just perfect as a potential romantic partner from Charlie, nonetheless this movie grated on my nerves something fierce. For everything it gets right there’s so much that can’t help but ring false, facile and slightly distasteful about this endeavor, the bad taste it left in my mouth after it had concluded one that took a little while to dissipate.

Pity, because Freeman is quite good, the veteran actor underplaying things with goofily sardonic aplomb. More importantly, even though they spend the majority of the story forced to remain at arm’s length from one another, he has marvelous chemistry with Baccarin, the Deadpool and Serenity actress a ray of continual sunshine the moment her character is introduced. This is especially true during a sequence where their characters go on a date not long after they’ve first met, Charlie taking Francesca to the most depressing off-off-off-OFF-Broadway play likely ever produced in order for him to not feel even a shred of happiness or sexual arousal. Freeman and Baccarin are delightful throughout these scenes, each actor exhibiting a relaxed chemistry I was instantly drawn to. Both are giving everything they’ve got, neither interested in allowing the uglier aspects of the story to become bothersome.

That they do become troublesome and annoying has more to do with Werner’s script and Winer’s uneven direction than it does anything else. I’m not expert in this disease and I certainly don’t know how fast or loose the pair are playing with the symptoms someone suffering from this form of cataplexy are forced to endure, but I do know how this affliction is showcased here frequently borders on becoming risibly obnoxious. The contrivances of when Charlie is suffering and when he has some semblance of control over himself is never entirely clear, the worse symptoms of his malady seeming to only show themselves when the plot most needs them to and not in a believably naturalistic fashion. These narrative contrivances grow more impossibly vexing as the film goes on, and by the time the main character found himself in a perilous situation dangling precipitously in and out of consciousness I could hardly have cared less.

Then there is the blatantly sensationalistic inclusion of Aunt Sylvia, who only seems to exist to give Francesca permission to fall in love with someone who might one day cause her great pain through no fault of his own. The fact this character isn’t wholly insufferable is in large part thanks to the massive talents of the actress portraying her, the almost always luminous Curtin finding a way to deliver a line or shoot a crooked eyebrow raise across a room that’s marvelous. But that doesn’t make Sylvia any less inauthentic and inexcusable, this one-dimensional caricature of a cancer patient a regressive, melodramatic insertion into a story that honestly didn’t even need her.

On the plus side, even though her part is relatively small Rauch is nothing short of splendid. The movie comes alive whenever she is up on the screen. Better, her character feels like one of the few that has any real agency outside of Charlie and Francesca’s non-romance romance. The humor involving Bethany is honest and true in ways the rest of the narrative seldom is, Rauch speaking with a hurriedly calm cadence that’s strangely comforting and amusingly goofy both at the same time. Better, the actress has a scene near the end with Freeman that’s just plain incredible, everything her character is angrily, yet still comfortingly, complaining about and stating ringing with an air of hauntedly wounded truth I wholly responded to.

If only the rest of Ode to Joy could have done the same. I’m not saying a good romantic comedy couldn’t have been made from this premise, with this cast I think it is obvious that isn’t the case at all, but because so much of it feels so fake and forcefully, almost purposefully maudlin, it just didn’t happen here. I find it difficult to get a handle on what it was exactly Werner and Winer were going for, so much of their romantic comedy reveling in its disease-of-the-week melodramatic excesses I found finding enjoyment in practically any of this close to impossible.

Film Rating: 1½ (out of 4)