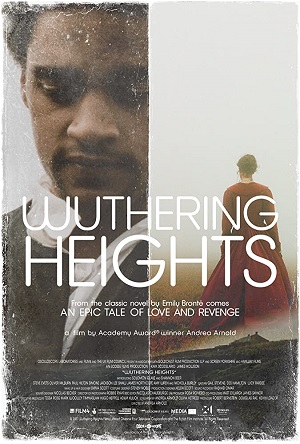

“Wuthering Heights” – Interview with Andrea Arnold

by Sara Michelle Fetters - October 17th, 2012 - Interviews

Never Satisfied

Director Andrea Arnold Dissects Wuthering Heights

British director Andrea Arnold is no stranger to success. She won an Academy Award for her short film Wasp in 2003. Her 2006 feature Red Road brought her a BAFTA for Most Promising Newcomer. But it was her 2009 effort Fish Tank which really put her on the map, that motion picture appearing on countless top ten lists around the globe while also winning the BAFTA for Outstanding British Film.

Arnold’s latest is an adaptation of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. Featuring a cast of unknowns as the star-crossed friends turned lovers Heathcliff and Catherine, in some ways this is the director’s most uncompromising work yet. The filmmaker eschews romantic conventions that are par for the course in prior adaptations of the novel, stripping events to their barest essentials allowing the tragic elements at the heart of Brontë’s prose to speak for themselves.

But this film almost wasn’t to be. Arnold, no fan of adaptations, initially had no interest in coming aboard, preferring instead to focus on original ideas. “The day the press release was sent out saying I was doing Wuthering Heights a friend texted me reminding me I’d said I’d never do an adaptation and that I’d never do a period film,” explains the director with a slight laugh. “She went on to say that when I did decide to work on an adaptation, a period piece at that, I managed to pick one of the most famous and timeless books of all time.”

“She went on to call me a stupid cow,” she says with an additional chuckle. “But, in a way, she was probably right. I always say that I don’t pick my films, that they pick me, that I don’t have a choice but to make them. In this case I think that’s true. Wuthering Heights came practically out of the blue. The other director had just dropped out, and I made this very instinctive decision to go for it. At the time, I didn’t think very much what that would mean or where things would go. I just sort of leapt in.”

It was in that leaping that Arnold was able to find what she felt was a new way into the story. She knew she didn’t want to follow the route of prior adaptations, most notably the 1939 classic with Laurence Olivier and Merle Oberon. She wanted to strip the prose bare, going back to the source material in a way she felt hadn’t been done before.

“I remember after reading the book that I felt that Heathcliff was this ruthless, darkly brutal character,” she states. “He had this very brutalized childhood, and I felt like I wanted to explore that. That I could explore that. You could say that it was a mad thing to do and a much different way of looking at the story.

“When I first arrived, there was a script that told things in a very different way. I realized right away I needed to see things through Heathcliff’s point of view and that I needed to find my voice in this. I went back to the book and wrote a new draft. In doing so I found my own way within the story, and I think the producers were happy I was able to do that otherwise I doubt they’d have wanted to hand me the material.”

One of the more interesting aspects of the film are the noticeable shifts in tone, the way the first half dealing with Heathcliff and Catherine as children is presented with such raw, emotional verisimilitude, while the second is more straight-forward in its handling on the story’s inherent melodrama. This is something the director herself is aware of.

“I think in the second half of the story that does happen,” says Arnold with a slight twang of disappointment. “I felt a little pushed around by the story in the second half, and sometimes that made it difficult to find my voice. But in the first half, I was really able to invest myself in the story. I was able to imagine Heathcliff and Catherine’s childhood. I allowed myself to play there and I really enjoyed that. I think by doing so I was able to give their tragedy a bit more punch in the process.

“The second half, when Heathcliff comes back, there are a series of events that are full of exposition, and I certainly felt the difference between these two halves. The melodrama of the story did take over a bit.

“But in the first half, I had more room and was able to allow things to breathe. I wasn’t as beholden to the structural dynamics of the source material. It was interesting for me to work on a film that does have a sort of organic story where you do have to hit those expected points or beats, and I did feel pushed around by that a little bit. But I think I managed to make the story my own, and I don’t think the second half would be as powerful as it is had I not found a new way into the lives of Heathcliff and Catherine during that first half.”

It should be noted that Arnold’s adaptation isn’t a complete rendering of Brontë’s book, the director choosing to close her version out where Heathcliff and Catherine’s love story reaches its climax. “I don’t know how I knew when to end things,” she admits candidly. “For the story we were telling, this just felt like the proper finishing point. Endings are always difficult, and when you’re writing you try numerous versions until you come upon the one that feels best for the material.

“I do actually feel sorry for not including the second half of the book. But a lot of films only seem to deal with the first half of the book because it does sort of have a natural break after Cathy’s death. Television adaptations don’t tend to do that, but then they can do more and are not limited by a theatrical running time.

“But I do feel the book is complete when it climaxes with Heathcliff’s death. At that point it comes full circle, which is satisfying because you do feel like he and Cathy can finally be together. But that wasn’t the story we were telling. We were focused on Heathcliff, and where we close feels real. It’s authentic. It feels like an actual end, even if the book does proceed onwards into Heathcliff’s future.”

More than the stark, bleak nature of the visuals, sound design is a vitally important component to this film’s success. There is no score, no musical accompaniment, only the arias of wind whipping through the Yorkshire highlands to counterbalance the emotional fireworks Heathcliff and Catherine are trying their best to make sense of.

“Early on I always said I want the wind to be the score,” states Arnold. “I wanted it to be its own character in the film. I spent long hours listening to the wind, and sometimes it would come through the door, down the chimney, through the trees and from beneath the floorboards. The rain would pound against the earth and the buildings. It was part of this world. The wind could be bold, it could be gentle, it could be angry and it could be calm. There was just so much variation. It was beautiful, and why would you want anything more?

“I had a fantastic sound team, and I’m glad you mentioned the sound because they all worked very, very hard. It was a decision I made early on, and my team embraced that challenge. I said, I don’t want anything that sounds like electricity, nothing that sounds modern. I didn’t want anything to sound like the way we hear them now. I wanted the world to sound completely different than anything we know, and this team worked incredibly hard to make this happen. I couldn’t be happier with what it was they achieved.”

Arnold insisted on casting unknowns to play Heathcliff and Catherine at both stages of their lives. James Howson, Solomon Glave and Shannon Beer are all making their debuts, while Kaya Scodelario is still something of a fresh face with only a handful of previous credits (most notably the BBC show “Skins”) on her resume. Each disappears into their roles, giving this story a timeless quality that may not have been possible had the actors been portrayed by familiar faces.

“I make it a point to cast a mixture of actors and non-actors in all my films,” says the director. “I like doing that. Here, because of the Heights and the Grange being two different places, the Heights being a place where you’re living right next to nature, things are quite visceral and on the edge. I wanted all the people to help give the place its raw feeling. By casting people who had never acted before it would bring about a different feeling, that they’d be forced to respond to the environment we were subjecting them to.

“At the Grange, I felt that this was a more mannered place, a prim and proper sort of environment, so I wanted veteran actors to fill those roles because I needed them to be able to exhibit those traits. I thought that by using properly trained actors for that place would give it the feeling I was going for. Even then, I still like to explore, I like to see how actors and non-actors work together to transcend cinema. I want to look at the face on the screen and feel whatever it is they are trying to say, even if they aren’t saying a word.”

The response to Wuthering Heights and to her previous features should be gratifying, the acclaim Arnold’s been receiving coming from all corners. One would imagine these accolades would warm the young director’s heart, but her actual reaction to all these kudos couldn’t be more surprising.

“I wish I felt like that,” she admits,” I truly do. I’ve always felt jealous of directors when they say they are happy with their film. I want to know how they feel like that, what they do to feel like that. I never feel like that. I never feel happy. You always reach for what’s quite clear in your mind and you hope that can achieve it, but that vision is so brittle it ends up getting beaten up a little bit along the way. You end up having some version of it but not the clear version you originally had in your mind. That’s just the nature of things.

“But, in answer to your question, no, I don’t feel happy. I wish I did, and I appreciate all the compliments and I’m glad people like my films, but I just don’t feel that way. I’m never satisfied. I always want more. I want to be able to achieve that vision I had when the film was just an image in my mind. I am my own worst critic and I always feel like I fall short.”

– Interview reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle