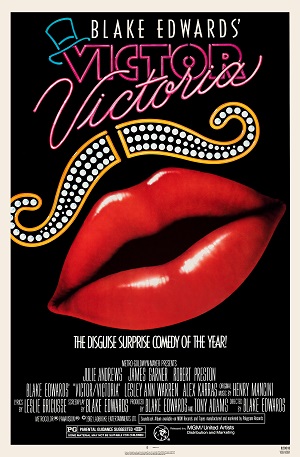

Unforgettables: Cinematic Milestones #3 – Victor/Victoria (1982)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - April 27th, 2022 - Features

Victor/Victoria: Blake Edwards’ 1982 gender-bending Parisian musical farce remains ahead of its time

NOTE: This feature originally appeared in the march 25, 2022 edition of the Seattle Gay News. It is reprinted here by permission of the publisher Angela Craigin.

It’s bizarre that Blake Edwards’ Academy Award-winning comedic musical triumph Victor/Victoria would still be considered groundbreaking if it were to be released today, 40 years after it originally debuted in theaters. A stylized, star-studded remake of writer-director Reinhold Schünzel’s 1934 German classic Viktor und Viktoria, the film’s brazen attitudes towards sex and gender are as provocative now as they were back in March of 1982.

I find that statement flabbergasting. While LGBTQI+ representation in cinema has substantively progressed, it’s a bona fide surprise that four decades later, a cross-dressing comedy set in 1930s Paris (featuring Julie Andrews as a woman pretending to be a man pretending to be a woman, in an Oscar-nominated performance) would remain so forward-thinking, given that it was made by the man behind the Pink Panther franchise, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, 10, and S.O.B. — all celebrated comedies with scenes so badly dated they’re unforgivably offensive.

Are there dated elements here as well? Certainly. Some of the language utilized by Chicago gangster King Marchand (James Garner) and his outspoken moll Norma Cassady (Best Supporting Actress nominee Lesley Ann Warren) wouldn’t pass muster today, and a couple of the homoerotic gags concerning his character, Marchand’s trusted bodyguard “Squash” Bernstein (former professional football player turned actor Alex Karras), and aging, self-described “queen” Carole “Toddy” Todd (Best Supporting Actor nominee Robert Preston) are a little cringy.

But Edwards celebrates the Queer components of his scenario with empathetic specificity. Scenes where Marchand wrestles with his sexuality are achingly authentic yet also goofily absurd. While his epiphany that being Gay is nothing to be ashamed of is understandably short-lived — the guy he’s fallen in love with turns out to be a genetic woman, after all — that doesn’t make his struggle any less sublime.

Even better are groundbreaking scenes of genuine longing and lust between Toddy and Squash. The sight of the two burly men in bed, while a source of genuine amusement, is not played for laughs. These men find something while entwined in one another’s arms, and Edwards holds this up as a genuine moment of affection and not some absurdity to be mocked, ridiculed, or snickered at.

Not that I understood any of that when I first saw the film at eight years old. Those facets unsurprisingly flew right over my head. What I loved were the colorful and energetic song-and-dance numbers. I loved the frantic silliness. I loved an early sequence in a diner where Andrews’ down-on-her-luck songstress Victoria Grant attempts to use a giant cockroach to score a free meal at a Parisian diner. I loved the squawky, cocksure exuberance of Warren’s vocal inflections, which made her come across like a living, three-dimensional cartoon.

Most of all, I was floored by the central conceit of a woman pretending to be a man and then subsequently masquerading as a woman to entertain spellbound audiences, receiving rapturous applause after each performance. This blew my little mind. Sure, I’d seen gender-bending material before — Looney Tunes reruns were a Saturday morning staple — but nothing like this. Here was the idea that a person could present any darn way they wanted to and receive roars of approval. And gosh darn it, did I secretly wish I could do the same and have my parents and all my friends cheer me on in a similar manner.

This was only a movie, though, not real life. I was not Julie Andrews, and as much as my parents adored the man, James Garner was not a member of our family. This was Spokane in the 1980s, not Paris of the 1930s, and no amount of wishing otherwise would send a flamboyant uncle like Toddy through our door to urge me to be myself and worry about the repercussions later.

I think some of this is why Victor/Victoria continues to resonate with me all these years later. I can treasure coming to the film much too early in life, then learning to cherish and respect it more and more as I grew older and began to understand everything it was trying to say. This was a celebration of gender, a story that went beyond ho-hum binary constructs and dared to look at the world through a lens free from condescension or bigotry. Sure, King Marchand and Victoria Grant get together in the old-fashioned way, but Toddy and Squash are allowed to express their sexual affinity for one another with equal fervor, free of judgment.

The jazz is hot in Victor/Victoria, and the romance sizzles courtesy of a fire ignited by the courage to be one’s true self, no matter what the consequences. There’s a reason this entry in Edwards’ filmography has flawlessly stood the test of time, and it won’t surprise me at all if we’re still singing this film’s praises in another four decades just as passionately as we are today, here on its 40th anniversary.

Victor/Victoria is available on Blu-ray and DVD from Warner Home Entertainment and to purchase digitally on multiple platforms. It is also currently streaming on HBO Max.