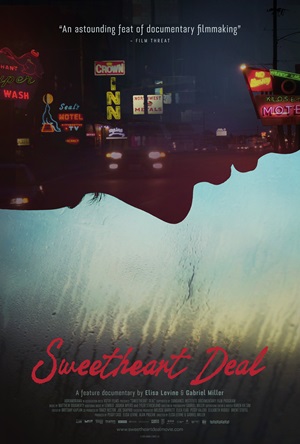

“Sweetheart Deal” – Interview with Elisa Levine

by Sara Michelle Fetters - September 27th, 2024 - Features Film Festivals Interviews

a SIFF 2022 interview

“A communal experience” – Seattle filmmaker Elisa Levine on her award-winning documentary Sweetheart Deal

Sweetheart Deal was the best film I saw during the 2022 Seattle International Film Festival. It is the best Seattle-set documentary since 1984’s Streetwise. Heck, I’d go so far as to state it’s arguably one of the best documentaries I have ever seen.

Shot over the course of seven years, with most of the action transpiring on Seattle’s Aurora Avenue North, the documentary follows four young sex workers, Krista (nicknamed “Amy”), Kristine, Sara, and Tammy, all of whom are friends with — and even sometimes looked after by — the RV-dwelling Laughn, aka Elliott. Their stores are heartbreaking, harrowing, and bracingly intimate.

Directors Elisa Levine and Gabriel Miller showcase an empathetic gracefulness as they chart each woman’s journey. They capture a time and a place that is both uniquely Seattle yet also sadly universal, as it’s far too easy to imagine agonizingly similar stories playing out on busy (and not so busy) streets throughout the United States.

But Levine and Miller also find a glimmer of hope in the center of all the heartbreak, broken dreams, addiction, and missed opportunities. Moreover, they are also inadvertent witnesses to a scandalously monstrous crime, documenting a horrific betrayal that’s practically unimaginable in its excruciating magnitude.

Recently, and now that Sweetheart Deal is on the cusp of a theatrical release,I was also able to briefly get in touch with Levine to discuss how things have evolved in the time since her film’s festival debut.

“This journey has been incredibly difficult yet fulfilling on so many levels,” she said. “Sharing Sweetheart Deal with audiences at film festivals was one of the most rewarding parts of the process. There’s something magical about watching it in a theater, surrounded by people who are fully engaged with the story — it’s a communal experience that amplifies the emotional impact of the film in a way that’s hard to replicate elsewhere.

“Winning the Seattle Film Critics Award and various other accolades has been an unexpected but deeply gratifying acknowledgment of the hard work and dedication our entire team poured into this project. But what truly stands out for me are the conversations I’ve had with viewers after screenings — people who see their own humanity, their own struggles or triumphs reflected in the film. Hearing how Sweetheart Deal resonates with them, how it stirs emotions and sparks discussions, reminds me why we made this film in the first place. As we move into the next phase with the theatrical release, I feel an overwhelming sense of gratitude and anticipation. I can’t wait for even more people to experience the film.”

Co-director Gabriel Miller tragically passed in July of 2019, a little before Sweetheart Deal had been completed and well ahead of when it would begin to intimately connect with festival audiences. “I think Gabriel would be incredibly touched to see how much the film seems to mean to people,” reflected Levine. “Our ultimate goal was for audiences to see themselves in these women and to feel like they truly know them, just as we did.

“Gabriel’s work behind the camera was essential in achieving that connection. His cinematography style, along with his patience, was crucial in translating their stories and struggles into a visual experience that deeply resonates with viewers. His approach allows the audience to feel as though they are right there with [these] women, sharing in their experiences and emotions.”

As for the documentary hitting theaters now, right in the middle of an election year, when questions of a woman’s right to bodily autonomy, criminalizing sex work, homelessness, LGBTQ+ rights, and other important social issues are at the forefront of the political conversation? “We do feel that the timing of Sweetheart Deal’s theatrical release is particularly right,” stated the filmmaker emphatically.

“In an era when many issues are highly polarized, the film addresses topics like addiction, trauma, sexual abuse, women’s rights, and sex work in a way that cuts through partisan divides. Our hope is that it can ultimately unite people and spark conversations about these crucial issues, rather than deepen existing divisions.

“Much like how support groups for parents who have lost children to addiction focus on shared human experiences rather than politics, we hope that Sweetheart Deal will transcend political boundaries. By highlighting the resilience and struggles of the women in the film, we aim to bring people together to discuss solutions and understand what truly matters, beyond political affiliations. Ultimately, we believe the film speaks to everyone and offers a chance for collective reflection and dialogue.”

The following are the edited transcripts of my wide-ranging conversation with Levine when I had the pleasure to sit down with director back in April of 2022 to discuss her film, the truth-is-stranger-than-fiction twist involving Elliott, and the rapturous reception the doc was receiving from festival audiences:

Sara Michelle Fetters: I am so glad we’re getting the opportunity to talk, because your doc blew me away. I was literally rewatching a section of your film right before we sat down. There’s so much here to think about and dissect. It’s extraordinary.

Elisa Levine: Thank you. Thank you so much. I’m curious, which part were you rewatching?

SMF: The part you would likely suspect. The third act. The point where everything…

EL: Goes sideways.

SMF. Exactly. I want to start closer to the beginning, the very beginning. When you and Gabriel started this project, what were your expectations? Did you have any preconceptions as to the type of stories you were going to be showcasing?

EL: In the very early days, I had no idea that I was even going to meet Elliott, the self-proclaimed “mayor of Aurora,” because the project was called Aurora Stories at that point, and I was still looking around for those stories. It wasn’t until meeting him that I found the entry point into this world.

I think we had in mind that we wanted to shoot a cinema verité film. We wanted to shoot observationally. We were very much influenced by Streetwise, and we were looking at that as a guideline in many ways. We knew we wanted to tell human stories, but yeah, we didn’t know at that time where it was going to go.

We were guests in that world of Aurora. We were gradually learning our way around and trying to understand what was going on. In the beginning, I was so naïve. I didn’t even realize that most of the women, at least at the time, were out there because of addiction, primarily heroin. We always had it in mind that we wanted to…tell a human story, and humanize people, but we didn’t know where it was going to go. We didn’t know who was going to allow us to film their lives.

SMF: Were you surprised that these women would let you so fully into their lives for such a long period of time?

EL: I was very surprised. I remember showing an early work sample of this at a Seattle Documentary Association retreat many years ago. …We had captured just a little bit of stuff at that time, and I remember standing up [in front of] everyone, and [saying], “Does anyone want to answer any questions about the processes of documentary filmmaking? How do you get verité? How do you get it? I don’t know how to do it.”

It ended up being that you just do it. You tell people that you’re there and you establish relationships, but you then tell people that “we’re invisible.” But a lot of it is relationship building, though, prior to that. If you’re successful, then people eventually will get into the mode of ignoring the camera.

Don’t misunderstand. They’re always aware the camera’s present. But they will get into the mode of doing what — at least it’s what I felt like while shooting — they normally would be doing if you were not there.

You never know, of course. You never know how much the camera is influencing. But we were hoping that things were not going to be performative. It was these four women who really embraced us and wanted their stories told. We ended up focusing on them and built strong relationships, really close relationships.

SMF: When you build those relationships, and because this is such, as you say, a verité style of filmmaking, how emotionally difficult was it for you as filmmakers to observe everything that was happening, ask these difficult and tough questions, and not want to become involved yourselves?

EL: Can you be more specific?

SMF: Like with Sara or with Krista. When you witness the decisions they are making. When you see what is happening to them. You’ve spent so much time forging these relationships, so it had to be difficult sitting there, watching events transpire as they do.

EL: When you’re working with people this closely, you do become friends. It just happens, and our relationships were really close. There were many hours that we spent with the camera off. There were many hours that we just spent with the women when they needed us: a ride to the methadone clinic, sitting next to Sara in the emergency room, stuff like that. We were just spending time with them because we cared about them as people.

If anyone ever asked us for anything, except for money, we tried to help. If anyone was ever like, “I need a referral to a needle exchange” or something like that, we tried to help. We wanted them to get out of that life. We wanted that for them. But we were also very aware that they didn’t want us to fix everything for them. They didn’t need a savior.

And we were in no position to save them! We were in no position to tell somebody that they needed to go into treatment. Heck, they’d already been through treatment a dozen times, and they didn’t want somebody coming in and telling them, “This is what you need to do.” They would’ve stopped talking to us day one.

But we really wanted to honor where they were at, what their struggles were, and what the story that they wanted to tell. But, yeah, that’s a tough and interesting question.

SMF: And then there is Elliott…

EL: Yes. Elliott. There’s lots to unpack there.

SMF: When did you all connect? At what point did he become so comfortable letting you all in to his world and his relationship with the women of Aurora Avenue North?

EL: I initially came across Elliott in 2009. I was looking around for stories on Aurora, and he was outside working on the generator of his RV, up by the St. Vincent’s around 135th. I had been talking to several people, but a lot of them were not ready to talk — people who were living in RVs and the like. There wasn’t that much of that in Seattle at that time, and there were even fewer who were brazen enough to park right on Aurora.

Elliott didn’t showcase any reticence to our presence. He didn’t have that. If anything, he was like, “Well. Where have you been?” It was like we were old friends. When I came across him, he seemed to want his story documented. He seemed to jump in front of the camera.

I think I initially did the pre-interviewing with him, stuff like that, and eventually he let us start filming inside the RV. Elliott told me his whole spiel: I’m the mayor of Aurora. I’m the guy to know. Everybody knows me. He was portraying himself as really creating a community atmosphere. He was profiled in Real Change, and he was putting forth the image that he wanted to portray about himself.

SMF: With what we end up learning about him, things Seattleites will likely be familiar with, what with all the local news coverage at the time, did you or anyone else in your team have any misgivings about Elliott? What were your feelings when you started to get to know him?

EL: I definitely did not. Initially, he was like a grandfatherly figure, which is funny now. But no, I didn’t have that, but I was gradually learning what exactly was going on, and then it was becoming apparent as things went on that he was portraying what he wanted everyone to see: that he wanted everyone to kick their habit, that he was there to protect them.

Well, maybe not everyone. But almost everyone. His RV, it was like a rest place to stop and get cared for. And not just for women but also for men too.

SMF: When did it become apparent things were more off with him than you suspected? Was it when the police arrested him? Before that?

EL: It took a little time to put together and realize that there [were] any relationships or whatever going on between him and the women. We filmed something like 350 to 400 hours of footage. As things went on, there were definitely moments where we’re just like, “Is this guy as great a deal?” There were definitely moments of doubt.

One day, people going in and out of his RV would be like, “I’m so mad at him!” But then the next day they’d be proclaiming, “I love him so much” or “He’s such a good friend.” You couldn’t keep up, and it was different for each person. But, yeah, I think this was the point where we were picking up that Elliott was not a saint. But was he also the best option out here for these women? No one else seemed like they were stepping up to help. It was confusing.

But as far as the stuff with the allegations and what he ended up being arrested for and everything? And then sentenced for? We did not have any clue that he was doing unconscious sexual assault… Gabriel couldn’t believe it at first. That was really freaking disturbing to find that out. Reading the police report and stuff like that, that was what made me really feel sick. I threw up when I read it.

After that and then looking back at the footage, going through it all again, in retrospect, there were little things that you pick up on after finding all of this stuff out. It brings a whole new light to what we had been doing. There were so many pieces of footage where I was just like, “How did we not put all of that together?” It stings.

SMF: Ultimately, what do you hope audiences take away from the film?

EL: I think the most important thing is being able to connect with these people, with the women in the film, on a human level. I think that if you’re able to see yourself, or see someone you know in them, in those women, then something’s working. It’s the beginning to bringing a deeper understanding of why people might get into addiction and how difficult it is to get out, even when these individuals are trying so hard to do so… and often ending up back right where they started… If we can understand, maybe we can be in a better position to help. Wouldn’t that be great?

– Interview reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle