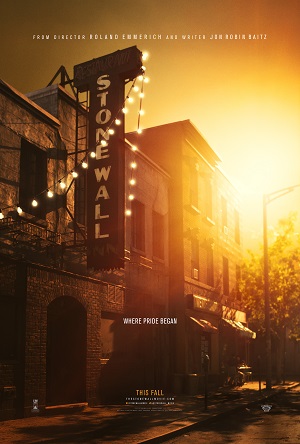

Revisionist Stonewall Worth Rioting Over

Danny Winters (Jeremy Irvine) has come to Greenwich Village in New York City after being thrown out of his small town farmhouse by his angry father. It is the summer of 1969, and the young man has dreams of someday becoming an astrophysicist working for NASA, hoping to start laying the groundwork to do it when he starts at Columbia on an academic scholarship in the Fall.

But, right now, at this moment, he’s homeless. With no place to stay and no friends to speak of, he’s taken in by teenage hustler Ray (Jonny Beauchamp), the flamboyant, outspoken kid seeing a kindred spirit in Danny that he finds irresistible. Soon the two are quick pals, hanging out at the mob-owned Stonewall Inn (where Ray gets the opportunity to spend time as Ramona, a far more comfortable alter ego), one of the few bars in New York that risks being closed down by law enforcement for serving alcohol to homosexuals. Times, however, as the song says, they are a-changing, these two about to be at the center of a storm that will help usher in a new dawn for LGBT civil rights unlike any the world had ever seen before.

It’s hard to always know where the line between historical fidelity and dramatic license should be drawn. If a filmmaker were going for down-the-line, no deviating from the truth recounting of events then a documentary presentation would be the road to travel upon. But, in the case of narrative reinterpretations, deviations from fact are unavoidable, streamlining and reconfiguring what happened when, to whom and why it did so in order to maximize emotional responses on the part of an audience typically par for the course.

But when is too far, well, too far? How much truth can you bend before the overall weight sidetracks the story you’re telling to the point it becomes unforgivable? Lord knows masterful motion pictures like Zero Dark Thirty and Selma have flirted with these questions. Heck, some, like Alan Parker’s Mississippi Burning and Oliver Stone’s JFK, have trampled right over the top of it yet still been motion pictures worthy of, if not all, the majority of the acclaim (and the Academy Award nominations) they ended up generating for themselves.

It’s questions like these one struggles over while watching Independence Day and White House Down director Roland Emmerich’s Stonewall. Very well acted, featuring a number of strong, emotionally affecting sequences that are hard to resist, the movie’s fumbling, almost offensive reinterpretation of a key moment in LGBT history derails things to such an extent goodwill is jettisoned out the window almost immediately. Working with acclaimed playwright and screenwriter Jon Robin Baitz (People I Know, The Substance of Fire), Emmerich’s decisions are nigh insulting, at the very least infuriating, the cumulative heft so massive one almost can’t believe it’s as nauseatingly disastrous as it proves to be.

I have no actual issue with the director wanting to compose a story looking at Gay homeless teenage hustlers during the late 1960s. I also don’t have nearly as much trouble with his desire to center events on a blond, blue-eyed, decidedly masculine farm boy searching for his identity in the middle of an effeminate, racially diverse group of friends who are in every way that matters far more interesting than he is. I don’t even take offense with him wanting to have this group be a part of the Stonewall Riot that took place on June 28, 1969, the crowd taking over the streets just after 3:00 a.m. that night so gigantic these characters easily could have found themselves a part of it.

But making Danny instrumental in instigating the riot? Having him be the champion everyone else rushes to in support? Sticking him with a hackneyed melodramatic coming out story so full of clichés they’re like a slap in the face every time the film decides to focus on them? Relegating Lesbian and Transgender stories integral to events at the Stonewall to the point of irrelevance? Weaving real life figures into the tale and then doing nothing with them other than have them spout a few uncomfortable platitudes before moving on to the next bit of sappy soapy nonsense? It’s too much to bear, watching it happen right in front of one’s eyes so stupefying it oftentimes feels like one great big laughable gag and not a piece of thoughtful dramatic entertainment meant to be taken seriously.

What’s most egregious, though, isn’t so much the reckless historical revisionism but the fact that Emmerich and Baitz do have a core narrative that’s built for a solid little period drama. I liked the focus on these kids. I liked hearing about their stories. I wanted to spend more time with them, was eager to see more of this history through their eyes. While none of the group Ray/Ramona associates themselves with break all that far beyond stereotype that doesn’t make their stories any less potent or valuable, and the fact the movie does them all such a grave disservice by the time of the climax maybe be the greatest travesty of them all.

There are some good performances throughout, not the least of which is Beauchamp’s, the talented newcomer making so much out of so little the overall effect is wondrous. Solid bit work is put in by more familiar character actors like Caleb Landry Jones, Jonathan Rhys Meyers, Matt Craven and Ron Perlman (playing real life figure Ed Murphy, the man’s colorful history as mob enforcer turned future Gay activist and icon sadly only hinted at), and while as horrendously plotted and conceived as Danny might be Irvine still does a nice job giving him life.

None of which matters. Sadly, for all of Emmerich’s filmmaking acumen (say what you will about the man’s big budget sci-fi spectaculars and their overall quality, and goodness knows I have, but all of them, from Godzilla to The Day After Tomorrow to 10,000 B.C. to 2012 to all of those in-between, are really, really well put together) his ability to deliver solidly scripted scenarios worthy of the effort he throws their way continues to leave plenty to be desired. As an attempt to move into more personal territory, as a vehicle for him to stretch, to leave the spectacle behind, I give him props. But as a movie worth watching? As a story I want people to see? Stonewall is a disaster, start to finish, and the only riots that should be associated with it are those of angry ticketholders who wasted good, hard-earned money to view it.

Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 1½ (out of 4)