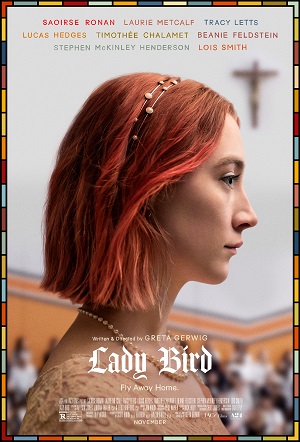

Lady Bird (2017)

by Sara Michelle Fetters - November 9th, 2017 - Four-Star Corner Movie Reviews

Gerwig’s Lady Bird Absolute Perfection

I knew I was in love with Greta Gerwig’s solo directorial outing Lady Bird less than a third of the way through. Her script is just so pure, so deft at bringing out whatever emotion it is aiming for, it ultimately achieved a level of intimate authenticity that captured my imagination in a way that had me recalling the highs, lows and perplexing in-betweens of my own high school years back in the 1990s. Mixing the introspective resilience of Noah Baumbach’s Frances Ha (which Gerwig co-wrote) with the whimsical emotional dramatics of a 1980s John Hughes comedic melodrama like Pretty in Pink or Some Kind of Wonderful, the movie never hits a false note, each beat of the story building one upon the next to produce a melodious coming of age symphony that’s absolutely sensational.

Christine “Lady Bird” McPherson (Saoirse Ronan) has started her senior year of high school. While her grades are good, they’re not spectacular, and while she longs to get out of Sacramento in order to fly across the country to attend college on the east coast, it’s going to take some doing in order to see those dreams become a reality. Granted, her mother Marion (Laurie Metcalf) doesn’t see the point. With the local economy so stagnant, with her beloved husband Larry (Tracy Letts) laid off and their eldest son Miguel (Jordan Rodrigues) currently living back at home with his longtime girlfriend Shelly (Marielle Scott) even though they’re both Berkley grads, she just doesn’t think it will be possible for the family to find the money to assist their daughter in what she views as a fanciful flight of fancy. Marion feels her daughter needs to set her sights lower and go to school closer to home, no shame in attending a local college right here in good old Sacramento.

What follows is a year-in-the-life saga where Lady Bird pals around with best friend Julie Steffans (Beanie Feldstein), thinks she gets swept off her feet by the star of the school play Danny O’Neill (Lucas Hedges), attempts to become a part of the rich kids clique by making the acquaintance of Jenna Walton (Odeya Rush) under somewhat false pretenses and ends up making goo-goo eyes at delectable bad boy Kyle Scheible (Timothée Chalamet). She learns things about her mother that take her by surprise, says things to Julie she instantly regrets and discovers there’s so much more to her father than initially meets the eye. Through it all, the teenager keeps her own idiosyncratic point of view about the direction her life is going to take, realizing in the process which friendships are worth doing whatever it takes to save, that compassion should extend even to those we believe have wronged us and that family, in all its crazy, messed-up, backwards is forwards and up is down glory, whether it be biological or not, is always worth fighting for no matter what the cost.

Gerwig handles it all with rapturous grace and ruggedly steadfast perniciousness. She allows the beautiful and the ugly to coexist side by side, sometimes in the same frame. The relationships Lady Bird has with her best friend Julie, with her father Larry, with her brother and his girlfriend, and most of all the one she shares with her mother Marion, they all sparkle with a blissful specificity that is undeniably genuine. Gerwig refuses to sugarcoat things yet at the same time her film maintains a lithely balletic levity that’s intoxicating, all of which only makes the emotional extremes that fuel the drama that much more refreshingly mighty as events progress to their conclusion.

Ronan, so amazing in Brooklyn, so stunning in Byzantium and Hanna, so marvelously enchanting in Atonement, is as breathtaking as she has ever been as the title character. Lady Bird is her own person, but that doesn’t mean she is immune from falling into some fairly predictable teenage sinkholes, each decision a learning process that will have bearing on what kind of person this youngster will eventually become. Ronan brings a bright-eyed irascibility that is immediately captivating, watching her navigate through a complex maze of her own creation a constant joy. It’s a beguiling portrait of youth in revolt and adulthood in embryonic development that I instantly related to, the twice Oscar-nominated actress a divine presence who fills the frame with her charismatic joie de vivre.

Metcalf is even better. Marion is a woman from a different age, one who isn’t altogether certain how best to navigate the 21st century, especially when things inside the household get flipped on their head and she’s the one who needs to keep things financially afloat while Larry does what he can to find a new job. The way she butts heads with her daughter, one moment angry as a devil that Lady Bird’s refusal to listen and in the next instant overwhelmed with heavenly, heartfelt joy when she does something selfless or steps out of a dressing room looking gorgeously unsullied, all of it rings with a simple, hardscrabble truth that oftentimes broke my heart in two. Metcalf takes what Gerwig has gifted her with the character and run with Marion in directions that are a continual surprise, every facet of her performance echoing with a profound candor that’s sublime.

Working with a collection of behind-the-scenes craftsmen, including composer Jon Brion (Magnolia), editor Nick Houy (“The Night Of”), cinematographer Sam Levy (Wendy and Lucy), production designer Chris Jones (20th Century Women) and costume designer April Napier (Certain Women), featuring additional supporting performances from veteran character actors Lois Smith and Stephen McKinley Henderson, both of whom are perfect, Gerwig grants them all the freedom to create to the best of their collective abilities. At the same time, her control over things isn’t ever in doubt, the film never drifting off course no matter how outlandish some individual moments might appear to be. The bigger picture is always in focus, and while none of Lady Bird’s realizations are particularly original or unexpected, that happily does not make them any less profound in their truthful elasticity.

I’ve seen some terrific teenage coming of age efforts these past few years. Stephen Chbosky’s The Perks of Being a Wallflower is one of my favorite films of this century, while last year’s introspective stunner The Edge of Seventeen written and directed by the fabulously talented Kelly Fremon Craig only gets better with each passing day. There is a possibility Gerwig has surpassed the both of them with Lady Bird. It has overwhelmed my imagination and reignited within me creative desires I’d almost forgotten where there. As stated, I love this movie, and it’s hard not to believe that general audience who head to the theatre to give it a look will not end up feeling exactly the same.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 4 (out of 4)