Emotionally Muted Glass Castle a Transparently Maudlin Misfire

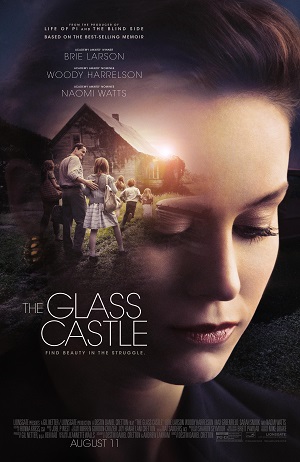

Based on the best-selling memoir by Jeannette Walls, reuniting writer/director Destin Daniel Cretton with his Short Term 12 star Brie Larson, there’s no question whatsoever that The Glass House should be a heck of a lot better than it is. Flipping back and forth through time as Walls (Larson), a popular New York gossip columnist working in a posh Manhattan office circa 1989, ruminates about her and her family’s nomadic life thanks to the wandering needs of her gypsy-like father Rex (Woody Harrelson), the movie is shaggy-eared melodrama that never earns the emotional connection with the audience it so clearly is aiming for. As strong as the cast might be, as wonderful as many individual moments are, the story itself never connects, the whole thing keeping me frustratingly at arm’s length for the majority of its lackadaisically paced 127 minutes.

Afraid to break the news about her recent engagement to investment banker David (Max Greenfield) to her free-spirited parents Rex and Rose Mary (Naomi Watts), currently squatting in a vacant and dilapidated building in Brooklyn, columnist Jeannette Walls gets advice from her two sisters Lori (Sarah Snook) and Maureen (Brigette Lundy-Paine) as well as brother Brian (Josh Caras) as to the best way to let them know what is going on. In the process, she reminisces as to what it was like growing up, the family constantly on the road avoiding debt collectors as they made their way across America looking for someplace to lay down roots. Ultimately, and much to Rex’s consternation, they end up in his former West Virginia hometown. As their father’s alcohol abuse and depression transforms him into a shell of his once energetically adventurous self, a 10-year-old Jeannette (Ella Anderson) comes to the realization that the only way either she or her siblings are going to escape a similar fate is if they all decide together to do whatever it takes to make something of themselves on their own without any assistance from their rudderless parents.

I don’t have a problem with the film’s structure, Cretton and his co-writer Andrew Lanham (The Shack) honestly keeping the flashbacks relatively linear in their presentation, drifting back to them in more or less sequence as Jeannette puts the pieces of her past back together as she decides what she wants to be doing in the here and now. It’s their ragged presentation that gets on my nerves. Some of these scenes, especially early ones with the protagonist at an even younger age (beautifully portrayed by Chandler Head), are just divine, Harrelson doing some of his best work walking a fine line between inspiration and madness that’s sublime. But others, especially after Rex fully allows himself to become an alcoholic bully devoid of imagination and sensitivity, they ring infuriatingly hollow, a banal pall descending upon the narrative that sadly refuses to dissipate until much too late to matter.

Cretton, who showed such marvelous restraint with his handling of Short Term 12, seems uncertain the best way to handle the material. He slathers composer Chandler Head’s (Grandma) nice if overly obvious score over scenes that might have been more effectively presented without any embellishments, choking the emotional life out of the movie in the process. There’s little room for the characters to breathe, their collective journeys never evolving in ways that feel authentic or genuine. Jeannette’s transitions happen because the story requires them to, not because they feel organic to her own personal story, diluting the inherent power of her resilient perseverance to achieve by a substantial margin.

Which is a true shame, because, at least according to Walls’s best-selling memoir, a Hollywood embellishment here and there aside, pretty much all of what’s depicted in this motion picture really happened. What she and her siblings overcame truly is extraordinary. More than that, the level of love and understanding they still share for their parents, the way they are all to weigh and measure Rex and Rose Mary’s various faults and virtues extraordinary. There is a selfless determination at the heart of Walls’s tale that cannot help but resonate with just about anyone who hears it, and as such it deserves a much better telling than the one that is represented here.

There are plenty of wonderful moments sprinkled throughout, and the movie does rebound slightly right at the end with a scene between Brie and Harrelson that ripped my heart into two and did so in a way that didn’t feel forced or false. The child actors are also wonderful across the board, while an early sequence inside a hospital room after one of the kids suffers an unimaginable accident straddles the line between suffering and jubilation rather nicely.

But the movie itself is frequently tiresome, moving around in such turgid circles of despair and ennui caring about any of Jeannette’s or her sibling’s collective achievements isn’t just difficult, it’s pretty much impossible. The Glass Castle feels in many ways like it wants to be this year’s Captain Fantastic, that it strives to show how the insane and the practical can walk hand-in-hand with far more comfortable ease than can be easily explained. Yet Cretton can’t balance the extremes, can’t differentiate between the various emotional nuances in a manner that’s truly satisfying. This adaptation just doesn’t work, making it one of 2017’s most massively disappointing misfires and a failure I’m going to be having a great deal of trouble getting over.

Film Rating: 2 (out of 4)