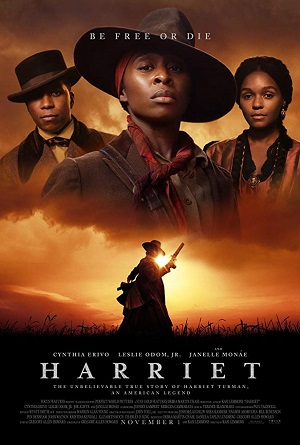

Historically Rich Harriet a Haunting Tale of an American Legend

It is 1849 and Araminta “Minty” Ross (Cynthia Erivo) has fled from slaveholder Gideon Brodess’ (Joe Alwyn) Maryland plantation before he can sell her to unknown new owners down South. With only guts, God and the North Star to guide her way, facing a number of horrifying trials and tribulations, she somehow makes it to the Pennsylvania border and ends up in the hustling, bustling streets of Philadelphia. She is welcomed by William Still (Leslie Odom Jr.) of the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society, and after a brief interview recounting her journey and documenting her past, he asks the young woman if she would like to give up her slave name and assume a new one of her own choosing. Minty rechristens herself “Harriet Tubman,” and in that moment finds a new purpose for her life far beyond any she could have imagined while working alongside her sister, brothers and mother as a disposable piece of property for Gideon Brodess.

It’s almost impossible to believe Harriet Tubman’s stunning story hasn’t been explored in the context of a major Hollywood biopic. A slave who made a break for freedom all on her own who subsequently reinvented herself and then became the most famous conductor on the “Underground Railroad,” so well known she was given the nickname of “Moses” and assumed to be a man because she was so cunning, her history is as American as they come. Her saga of triumph, tragedy, heartbreak, salvation, courage and sacrifice is beyond imagining, and as dark as aspects of it might be that does not make it any less essential. If anything, it is precisely because Harriet Tubman’s story touches on the worst, most inhuman aspects of the American experience that it must continue to be told, and as the old cliché axiom goes those unwilling to learn from the past are doomed to repeat it whether they want to or not.

Thanks to a powerhouse performance from Erivo and stellar direction from Eve’s Bayou and Talk to Me filmmaker Kasi Lemmons, biographical drama Harriet frequently lives up to the weight of expectation that comes tied at the ankles of anyone attempting to tell Harriet Tubman’s story. It is a movie that feels as if it understands this facet of the American experience in ways few other, similarly-themed motion pictures ever have. It brings a distinctly feminine point-of-view to this ugly section of history which puts things in a type of perspective I can’t say I’ve ever seen before, and for that I am beyond grateful.

Not that the director, for all her consummate skill behind the camera, can still avoid all of the pitfalls and traps of the historical biographical genre. There is something perfunctory and old fashioned about Lemmons’ and Gregory Allen Howard’s (Remember the Titans) screenplay that can dull the emotional impact of what is happening, and even if it’s only just a small amount that doesn’t make these missteps any less noticeable. There are also a few fantastical elements to how the pair approach Harriet’s experiences conducting runaway slaves on the Underground Railroad which border on the supernatural, her constant conversations with God likely to rub some viewers the wrong way.

But not me. These spiritual elements were ones I found to be some of the most intimately powerful in the entire movie. There is a distinct celebration of Harriet’s connection to her faith that feels pure and not in the slightest bit heavy-handed. It is an organic piece of her puzzle and one that adds so many additional layers of emotional complexity that I’m not sure I’d have responded as positively to the overall film if they were not present. No matter what one’s faith or background, whether they believe in the spiritual nature of humanity’s creation or not, religion here isn’t used as a cudgel or a battering ram to bludgeon the viewer into blindly accepting what is happening. Instead, Harriet’s faith is a core part of who she is and why she ends up believing so strongly she will succeed at whatever task it is she sets in front of herself to complete, all of which magnifies the importance religion played for slaves during this time period and how it blossomed into an crucial part of the African American communal experience going forward all the way to today.

I wish the movie could have spent more time with Omar J. Dorsey, the actor playing Bigger Long, a notorious slave catcher who is hired by Gideon to track Harriet down. I’d love to know more about his history and what led him to so callously hunt runaway slaves and return them to the White slaveholders to be beaten, brutalized and killed. It also would have been nice to get to know more about the workings of the Anti-Slavery Society and Still’s importance in laying the tracks for the Underground Railroad. The script just sort of presents everything as-is with little in the way of explanation, making this vital historical figure a little less interesting than he potentially might have been had Lemmons’ and her team decided to do more with him.

But it’s not his story. It’s not the story of Harriet’s family. It’s not Bigger Long’s story and it certainly isn’t Gideon Brodess’, either. No. This is Harriet Tubman’s story and her story alone, so the fact Lemmons keeps the focus entirely on her is understandable. Because Erivo so effortlessly rises to the occasion, and in large parts because the director’s script digs into her character in so many nuanced and refreshingly multifaceted ways, that not a lot of time is spent with many of the secondary or side characters is hardly an issue worth getting all bent out of shape about.

Not that other actors don’t make their presence felt. Alwyn is chilling as Brodess. Even better is Jennifer Nettles as his psychologically disintegrating mother, Eliza. Odom Jr. has a small handful of affecting moments, especially during that key scene where Still is first interviewing Harriet. Vondie Curtis-Hall gives one of the finest performances of his long career as Reverend Green, a man of the church whose fealty to the likes of Gideon and other slaveholders isn’t what it initially appears to be. Best of all is Janelle Monáe as Marie Buchanon, a born-free young woman who owns the boarding house Harriet takes up residence in. Her performance really snuck up on me as the plot progressed, her emotional permutations a thing of heartrending beauty.

There’s more of Harriet Tubman’s story just waiting to be told, many aspects of it Lemmons’ latest effort just doesn’t have the time to explore in the type of detail I was somewhat longing for (most notably the Civil War period which is only briefly touched on). But none of that changes just how good this motion picture is. It feels lived-in, Erivo disappearing so completely underneath her character’s skin I almost forgot it was the Widows and Bad Times at the El Royale actress I was sitting there looking at in awe. Harriet is more than a dramatic history lesson. It is a piece of filmmaking excellence I am almost certain to revisit, and a film I’m fairly positive I’ll appreciate even more once I have done so.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3 (out of 4)