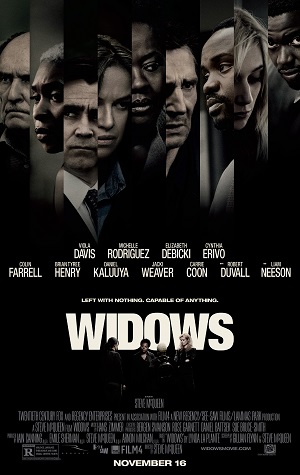

McQueen’s Widows a Socially Astute Heist Thriller

After their husbands are killed during an attempted heist of $2-million in cash, distraught widows Veronica (Viola Davis), Linda (Michelle Rodriguez) and Alice (Elizabeth Debicki) find themselves thrown together in common cause against a murderous adversary. Previously strangers by design, now all of them are the target of Chicago kingpin Jamal Manning (Brian Tyree Henry). He’s currently in a heated campaign against veteran politician Jack Mulligan (Colin Farrell) to become his neighborhood’s new alderman and is in need of cash for one last advertising blitz. It was Jamal’s money Veronica’s criminal mastermind husband Harry Rawlings (Liam Neeson) absconded with, and he’s given the wives 30 days to make good on the debt otherwise his bloodthirsty younger brother Jatemme (Daniel Kaluuya) will be paying all of three of them and their families a lethal visit.

Courtesy of her late husband’s notebook Veronica has a plan. Harry had outlined one last theft of $5-million and it only takes a tiny crew to pull it off. She’s certain that three of them can pull it off. She’s also convinced her chauffeur Bash (Garret Dillahunt), a devoted friend and confidant, to be their getaway driver. Veronica thinks that she, Linda and Alice can do this off mainly because no one expects them capable of such an audacious crime. But as well as everything seems to be going Jatemme is secretly monitoring the trio’s every move, and while he doesn’t know what it is they’re up to, he’s still positive Jamal won’t mind if he keeps tabs on the women all the same.

Widows, based on the 2002 BBC miniseries from “Prime Suspect” impresario Lynda La Plante, is magnificent. Director and co-writer Steve McQueen (12 Years a Slave, Hunger), working with Gone Girl author Gillian Flynn on the adaptation, has crafted a drama that touches on ideas of gentrification, gender inequality, political corruption, racism, nepotism and a whole bushel of additional hot-button social issues, all of it concealed in the guise of an adult-oriented heist flick that would make Michael Mann, John Huston and Jules Dassin all proud. It is a terrifically complex thriller, everything building to a stupendous conclusion that melds all of the various themes and ideas McQueen and Flynn had been playing with throughout the story to something nearing perfection.

I think what is most impressive is how the director juggles so many different plots and subplots with such effortlessness. Even more astonishing, McQueen and Flynn never lose sight that this is primarily Veronica’s journey, and while practically all of the numerous characters populating the film are given their individual moments to shine, she remains at the center of the maelstrom. She is the one Jamal goes to with his demands. She is the one who must be the first of the women to set aside her grief in order to try and look at their collective problem as clearly as possible. She is the one who is able to connect the dots as to why Harry’s plan went so wrong and resulted in catastrophe. She is the one that, if she doesn’t already know all the players personally, has the resources to figure out who they are and make their acquaintance.

With all that and more to play with, Davis is superb as Veronica. Her grief is palpable. Her pain is omnipresent. Yet her intelligence is never in doubt, even during those moments when she is second-guessing her plans and wondering whether or not she and the other women are doing to the right thing. Davis has a way of making the character’s stoicism feel like a shield against the trauma and the despair that’s threatening to overwhelm her, the shocking, unexpected ferocity of her reactions to unexpected twists and turns catching me by surprise. It’s a mesmerizing turn, one with delicate little nuances worthy of additional dissection and study, and for the Academy Award-winning actress this is a titanic performance that is unquestionably one of the finest of her justifiably lauded career.

She’s not the only one doing career-best work. Debicki, so wonderful in films as diverse as The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and The Great Gatsby, is a constant surprise as the browbeaten Alice, this damaged and abused woman finding an inner strength and a determined resilience she never knew existed in the first place. Then there is Kaluuya. In a performance that’s as far removed from his Oscar-nominated turn in Get Out as you can get, the actor is a demonic force of nature as the pleasantly homicidal Jatemme, the shudders crawling up my spine each time the character made an appearance justified considering just how terrifying this killer proves himself to be.

But everyone in the cast is great, especially Rodriguez, Farrell and Henry, each taking what could have been stock genre characters and doing something unforeseen with all of them. I was also blown away by an unrecognizable Cynthia Erivo, the Bad Times at the El Royale chanteuse crafting a performance for McQueen as a quietly dogged single mother struggling to keep her head above water that’s divine. Only Robert Duvall as the elder Tom Mulligan, constantly badgering his weasel of a son Jack, disappoints and not because the legendary actor gives a subpar performance. Instead, this is due to the routine way in which the character is scripted, his constant foul-mouthed antagonism more expected and commonplace than it is appalling or unanticipated.

From a technical standpoint, few 2018 motion pictures look, sound and move as well as this one does. Sean Bobbitt’s (Shame) cinematography is a master class in framing, his use of shadows, light and explosions of color stunning. Same goes for Joe Walker’s (Arrival) confidently kinetic editing, his ability to imbue each scene with a steady aura of menace and dread outstanding. As for veteran composer Hans Zimmer’s (Blade Runner 2049, Dunkirk) score, the way his music augments each of the individual scenes it’s so cleverly utilized within is close to extraordinary, and it’s hard not to believe a second Oscar might be on its way.

In the end, it is McQueen and Flynn’s script that impressed me the most. It’s apparent that they love these women, even the ones at the periphery portrayed by the likes of Carrie Coon, Jacki Weaver and Molly Kunz, the two filmmakers making sure each character has their own distinctive voice. Better, the duo allows them to have their own inner lives that they’re currently attempting to navigate. This helps make all of the women, and not just Veronica, Linda and Alice, feel authentic in their emotional dimensionality, giving the film an extra layer of realism that’s impressive in diverse specificity.

I figured out the story’s core twist early on, and I’m not entirely certain McQueen and Flynn meant for me to do so. But this didn’t weaken the film for me, its visceral power to amaze never waning making the fact I figured out what was going to happen at the end not matter near as much as maybe it should have. The final scenes of Widows have a haunting truthfulness that left me both shattered and hopeful in the exact same breath, the austere closing image a quiet plea for forgiveness, friendship and companionship that’s nothing short of flawless. It’s an unforgettable moment in an equally unforgettable movie, and I can’t wait for audiences to sit in the darkened theatre and discover its magnificence for themselves right away.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 3½ (out of 4)