Immaculately Composed Mank a Frustratingly Empty Disappointment

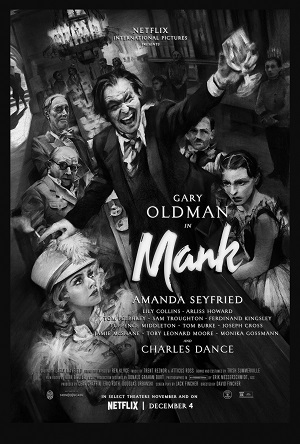

There are several things to like, maybe even love, about David Fincher’s spunky Hollywood Golden Age historical reinvention Mank. Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ inspired score. Donald Graham Burt’s (The Curious Case of Benjamin Button) superlative production design. Trish Summerville’s (Red Sparrow) magnificent costumes. Amanda Seyfried’s lively, captivatingly magnetic performance as silent-era star Marion Davies.

Yet, for my money Fincher’s latest is a disappointing slice of Hollywood hooey. Working from a script written by his late father Jake Fincher, it’s obvious this long-gestating project is a labor of love for the director. But although immaculately made, and as strong as the ensemble might be, it didn’t take long for this lionizing biography of Oscar-winning Hollywood legend Herman J. Mankiewicz to rub me the wrong way. It is an exercise in technically precise tedium, and as flawed as they may be, I’d much rather watch Fincher’s Alien3 and Panic Room on repeat for the entirety of December if it meant I never had to think about Mank ever again.

The key portions take place in flashback during 1930. Invited by his former writing partner and friend Charlie Lederer (Joseph Cross), former New York playwright and current Hollywood screenwriter Herman “Mank” Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman) spends a fateful weekend at San Simeon. This is the fabled playground of newspaper tycoon William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance). He lives there with his mistress, actress Marion Davies, who also happens to be Lederer’s cousin, which is what allows both he and Mank to become frequent guests of the larger-than-life newspaper tycoon.

The elder Fincher’s nonlinear script flashes between 1940 and the writing of a script which will become Citizen Kane (given the tentative title “American”), events at San Simeon and an increasingly drunken Mank demolishing his relationship with studio heavyweights Irving Thalberg (Ferdinand Kingsley) and Louis B. Mayer (Arliss Howard). There’s also the establishment of the Writers Guild and the California gubernatorial campaign of Upton Sinclair (Bill Nye), amongst other events, as roughly a decade of rambunctious Hollywood history sprints across the screen over the course of the picture’s 130 minutes.

Fincher’s eye is as good as ever. He stages moments that blow the mind. His use of sound, how he blocks a scene, the way actors and props are so precisely placed within a frame, all of it is masterful. Unfortunately, this technical virtuosity is in service to a story that’s so haphazardly structured that watching the finished feature becomes more of a studious endeavor than it is a pleasurable one. Worse, I didn’t feel like I learned anything of consequence, the director never convincing me Mank was someone I needed to be spending so much time observing.

There are a few more issues that both confuse and vex me. One is a technical matter. It’s clear Fincher is emulating the structural formality of Hollywood in the 1930s and ’40s, and while Erik Messerschmidt’s lush B&W cinematography is pretty enough to look at, formatting the frame in a 2.20:1 widescreen aspect ratio instead of the 1.37:1 Academy ratio utilized by Orson Welles for Citizen Kane baffles me. But this is a nitpicky issue, and I won’t deny that, but considering every other cinematic trick of the trade Fincher utilizes, this one still rubbed me the wrong way and I’d be remiss if I didn’t say so.

One of my other primary problems is plain bizarre. While historical biography does not mean the viewer is going to get documentary-like exactitude as far as adherence to fact is concerned, there is an implied presumption that basic truths are going to be adhered to. Mank blatantly refuses to do that. It’s stupid. More to the point, it’s egregiously noticeable in ways that stick out like a sore thumb.

Case in point, there is a key reference to Universal Pictures landmark monster movies (Dracula, Frankenstein, Bride of Frankenstein, The Mummy, The Wolfman, etc.) showcasing Mank’s disdain for them and their studio. Problem is, this happens before the majority of the pictures had been made let alone released. Fudging dates is one thing, but this is absurd, the laziness of the moment taking me out of the story entirely while also making it even more difficult to believe any of what was happening up on the screen might have taken place.

Seyfried is very good, and many of the scenes at San Simeon are superb. The majority of the supporting players slip into their roles with ease, and if one does choose to watch Citizen Kane directly before giving Fincher’s opus a gander it’s likely they’ll appreciate this effort a bit more than they otherwise may have. As for that aforementioned Reznor/Ross score, it’s outstanding, and if not for their even more exhilarating work on Pixar’s Soul (releasing Dec. 25 on Disney+), I’d almost go so far as to say it’s one of the year’s best.

If only I had cared? If only I felt any of this mattered? If only I was interested in the story being told and felt like I was learning something about Herman J. Mankiewicz, his part in the making of Citizen Kane and gaining new insights into Hollywood’s Golden Age that I’d never have garnered without watching the movie? Then maybe I’d be willing to cut Fincher some slack, to give his latest the benefit of the doubt and feel like viewers should take a chance on it even with a handful of noticeable reservations. But that’s not the case, Mank nothing more than a metaphorical celluloid sled of failed dreams and misguided ambition burning to ash in a fiery furnace fueled by frustratingly combustible emptiness.

– Review reprinted courtesy of the SGN in Seattle

Film Rating: 1½ (out of 4)