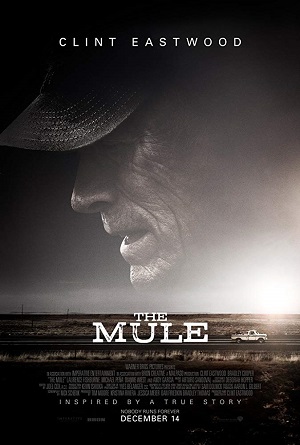

Eastwood’s The Mule a Bumpy Introspective Road Trip

Earl Stone (Clint Eastwood) is wondering what happened. The elderly daylily farmer’s business is in foreclosure, his ex-wife Mary (Dianne Wiest) can barely tolerate being in the same room with him and his daughter Iris (Alison Eastwood) hasn’t spoken a single word directly to her father in over a decade. Only his doting granddaughter Ginny (Taissa Farmiga) appears to be the only one in his family who wants to spend time with him. But when Earl forgets that he’s promised to help pay for part of her upcoming wedding for all his granddaughter’s claims to the contrary even the status of that relationship seems like it could be in jeopardy, and the thought he could let her down the same way he did Mary and Iris so many times over the decades is tearing him up inside like it never has before.

A chance encounter leads to the unique possibility to make instant cash that could potentially solve at least a couple of Earl’s financial problems. Asked to drive a mysterious package cross-country, the farmer who used to spend so much time behind the wheel traveling couldn’t be happier to be back hitting the open road transporting goods for an employer willing to pay him handsomely for doing it. It’s a win-win as far as Earl is concerned, and soon he’s able to help Ginny with her wedding, pay off the past due mortgage on his farm and to buy a fancy new truck to make these trips even more enjoyable. But the old man’s success comes with a price, and soon his Mexican drug cartel kingpin employer (Andy Garcia) decides to up his payloads as well as assign him a handler, Julio (Ignacio Serricchio). Earl’s accomplishments have also caught the eye of ambitious DEA officer Agent Bates (Bradley Cooper), he and his partner Agent Treviño (Michael Peña) determined to bust this mysterious drug mule and get his truck and its cargo off the road for good.

Director/star Eastwood’s (Unforgiven, American Sniper) latest effort both behind and in front of the camera The Mule isn’t the ticking clock thriller that description might make it sound like it is. Sure there is a little in the way of tension during the film’s climactic sequence, but for the most part this story is more concerned with being an intimate character study of a deeply flawed man trying to rewrite his own personal history by agreeing to do a bad thing for even worse people. Earl is a Korean War veteran who reveled in being a successful farmer and salesman and reveled in all of the affection from others this brought him. But it also made him a terrible husband and an even worse father, his inability to show kindness to the people he purported to love putting a dark cloud over his life that only grew darker and more storm-ridden as time went on.

Inspired by a New York Times Magazine article written by Sam Dolnick, it’s hard not to feel like Nick Schenk’s screenplay is perfectly tailored to Eastwood’s current sensibilities as a storyteller. He did write the filmmaker’s 2008 hit Gran Torino, after all, and the differences between Earl Stone and Walt Kowalski are negligible and more a matter of temperament. Each is an old man stuck in his ways whose eyes are opened to new possibilities due in large part to circumstances well beyond their control. But where Walt was a grizzled and angry loner, Earl is a happy-go-lucky everyman who enjoys the various experiential wonders life on the road has offered him. More, he’s eager to convince others, even if they be lethal, gun-toting members of a drug cartel, to look at life in same exact way.

When the movie focuses on items like this, with Earl introducing Julio to the glories of a pulled pork sandwich at an out-of-the-way eatery or slowly driving through some eerily desolate salt flats simply because he can, it’s actually kind of terrific. There’s an observational magnetism to these road trips that’s like something out of Wim Wenders’ drama more than it is anything else. Eastwood and cinematographer Yves Bélanger (Brooklyn) seem to both revel in these segments of the story, and as such there is a lyrical poeticism to this endeavor that’s moderately striking.

The problem is that the rest of the film just doesn’t measure up. As great as Eastwood is as the titular character (and he’s close to perfect), the stuff between him and his family is either too nondescript and unfocused to matter or so overly melodramatic and covered in treacle to feel remotely authentic. All of the stuff with the DEA is just sort of there with virtually no energy driving it forward, and other then one excellent scene between Agent Bates and Earl at a roadside diner when the former has no idea who the latter is, I found precious little about this subplot to get excited about. As for almost anything having to do with the Mexican drug cartel, the only reason it isn’t a true waste of time is in large part thanks to both Serricchio and Garcia. As it is this core part of the story is still frustratingly subpar, sometimes worse than that, and on more than one occasion I was struck by just how disagreeably offensive scenes between the various members of the cartel were on the verge of becoming.

There are some additional hiccups, not the least being the handful of scenes where Earl is depicted as that stereotypical jovial elderly racist whom were just supposed to laugh off for saying so many horrifying things simply because he does so with a congenial laugh and a helpfully polite smile. But Eastwood and Schenk get back on solid pavement with the film’s final 15 or so minutes. While still not particularly thrilling, there is an emotional maturity to the climax that I found movingly genuine. Eastwood and Wiest (whose character deserves so much better than what the script sadly is willing to give her) have one marvelous scene together near the end that put a gigantic lump in my throat I never could have anticipated, while the final confrontation between the DEA and Earl transpires with a deliberate brevity that’s fittingly superb.

Is that enough to make this one worth seeing in a theatre? I’m honestly not sure. Its various missteps are pretty egregious, and anyone going in expecting an old school thriller overflowing in suspense and tension will almost certainly walk out afterward more than a bit disappointed. But Eastwood remains a confident craftsman who knows how to tell a story and enjoys putting more emphasis on character and on mood than he does in engaging in inconsequential visual theatrics. While a second-tier effort from the Oscar-winning veteran that still makes The Mule better than a lot of other filmmakers’ first tier selections, and for fans of the director this could be a solid matinee option worth hitting the road in order to see.

Film Rating: 2½ (out of 4)